In the Spotlight

In the Spotlight

Doctors and other medical staff have to work very hard, but receive very low salaries and benefits.

|

| Doctors perform an operation at Saint Paul Hospital in Hà Nội. – VNA/VNS Photo Dương Ngọc |

Viet Nam Newsby Thu Hà - Bảo Hoa

When Trần Xuân Hương’s husband was hospitalised last year after his cancer got worse, she took him to a big military hospital in Hà Nội in the hope of saving his life.

The first two days there, she noticed that other patients were getting infused with a bottle of medicine that her husband did not get.

Worried, she asked the doctor if her husband could get that medicine and was told she would have to buy it from outside the hospital for VNĐ1 million (US$44) per bottle.

After she had discretely handed over an envelope containing VNĐ1 million ($44) to the doctor, the medicine was made part of her husband’s daily regimen.

“He was a high-ranked military officer who could legally enjoy the treatment, but in the end we had to pay for it in an illicit way,” Hương, angry a year after the incident.

Giving envelopes to medical staff has been a “problem” in Việt Nam for long, but there is more to it than meets the eye. It is not a straightforward ethical issue, and the economic, social and historical context to this practice has to be looked at.

In June last year, a doctor with the Việt Nam Cancer Hospital (K Hospital) in Hà Nội was suspended from performing operations after a video clip of her taking a stack of envelopes from patients emerged in social media.

Although no official statistics have been issued in recent years on medical staff receiving bribes, ‘giving envelopes’ is virtually an unwritten law for patients in public hospitals.

“I have been giving envelopes for the last 10 years,” said Hương, who had to visit hospital frequently because of her late husband’s illness.

She said that although the doctors she met were all nice and did not ask for money, an envelope effectively secured better care for her husband.

|

Doctors and other medical staff have to work very hard, but receive very low salaries and benefits. Thus “envelopes” are taken to supplement their meagre income, almost as a matter of course, Dương Minh Tuấn, a doctor with the Vạn Hạnh General Hospital in HCM City told Việt Nam News.

|

| Doctor Dương Minh Tuấn |

Based on regulations issued the Ministry of Internal Affairs, a medical graduate (often after six-eight years of studying) who has an official employment contract with a hospital will receive a starting salary of VNĐ2.7 million ($119) per month including medical insurance. This is less than the income of a domestic helper who typically receives VNĐ4-5 million per month.

After six to nine years when they have become primary doctors, lecturers and associate professors, their salary will be raised to some VNĐ7.8 million ($343). And even when they climb to the top levels of their profession, becoming high-ranking doctors, senior lecturers or professors, they will be paid just VNĐ9.2 million ($408).

The payment is far too low compared to the heavy pressure and workload that they have to endure daily, Tuấn said.

“In foreign countries a doctor may see about 10 patients per day, while it’s 100 per day for a doctor in public hospitals in Việt Nam,” Tuấn said, harking back to his experience working as an intern at some public hospitals in Hà Nội.

“Besides normal shift, a doctor is normally subject to an all-day-long shift every four days, for which the extra payment ranges from VNĐ50-100,000 ($2.2-4.4).

“Doctors are normal persons who also need money to live,” said Tuấn, who added that while he himself has never taken an “envelope”, he was not judgmental about any colleague that did.

|

| Doctor Phạm Nguyên Quý |

Phạm Nguyên Quý, a Vietnamese doctor at the Kyoto Miniren Chuo Hospital in Japan, concurred with Tuấn.

Quý said that medical practice in Japan, like elsewhere in the world, is considered a ‘noble’ profession. Medical practitioners, thus, are paid well, often two to five times higher than those doing manual work.

“Of course, in Japan, it is not only about how much you are paid, it is also about one’s honour and prestige, but at least, doctors here are paid well enough to feel secure about their life,” said Quý.

Yet, low salary is not the whole story.

Public hospitals in Việt Nam, especially at central-level, have been being overloaded for years to the point where three or four patients sharing one bed is a common sight, while private hospitals operate at just 50-60 per cent of their capacity, according to Việt Nam Social Security (VSS).

The number of hospital beds in public hospitals accounts for 85 per cent of the total number of beds. The number of inpatients and outpatients at these hospitals is more than 90 per cent of the total number of patients at all hospitals, according to VSS.

|

| Doctor Nguyễn Văn Phú |

The overwhelming number of patients coming to public hospitals increase the amount of work and pressure on doctors, requiring them to work harder for the same meager salary, said Nguyễn Văn Phú, vice director of the Việt Nam Sports Hospital in Hà Nội.

The long wait before being treated and degraded quality of service in public hospitals because of overcrowding also push many patients to opt for the ‘envelope solution’ to secure faster and better service. Over the years this has settled into a common practice.

Then there is a long-standing Confucian-rooted tradition of giving gifts. Many Vietnamese patients don’t treat good medical service as a right, but a favour that they seek from medical staff, and giving envelopes and gifts is a way to express appreciation.

Therefore, while there are “rotten apples that spoil the barrel”, Phú said that in some cases, accepting envelopes or gifts from patients was not necessarily bad, but a “cultural thing”.

“Giving gifts to express gratitude has been a culture in Việt Nam for years. So I think there are cases where it is fine to accept gifts from patients. You just need to be very careful that the gift is based on goodwill, and don’t cross the line.”

Hanoian Trần Thu Minh also agrees that giving envelopes or gifts to doctors is not always bad. She did it herself four years ago after her husband was discharged from the Bạch Mai hospital after a stroke. Minh gave her husband’s doctor a gift set that include a souvenir watch and a wallet containing VNĐ1 million ($44) because she thought it was the right thing to do.

“I could see that he did his best to find out the cause of my husband’s stroke and help him recover,” Minh said.

However, the next time Minh took her husband to the hospital for a check-up, the doctor gave the money back to her.

“He thanked me for the gifts, but refused to take the money, saying that he never accepts ‘envelopes’,” Minh said.

Doctor Quý said the ‘thank-you’ practice exists in Japan as well.

“As far as I know, doctors at private hospitals sometimes receive money or in-kind gifts, feeling that refusing them may disappoint their patients. In some cases, the doctor calls the patient back the next day to let them know that the money is being added to the hospital’s welfare fund.

“The important thing is that whether patients give gifts or not, the doctors’ attitude and service is not affected.

“However, doctors at public hospitals or the institutions themselves are not allowed to receive money or gifts of value higher than JPY5,000 ($44.6) because they are already paid for by the State.”

Việt Nam’s Ministry of Health (MoH) has already taken tough measures in an attempt to tackle corruption in the healthcare sector.

These include a “Say no to envelopes” campaign that was launched way back in 2011.

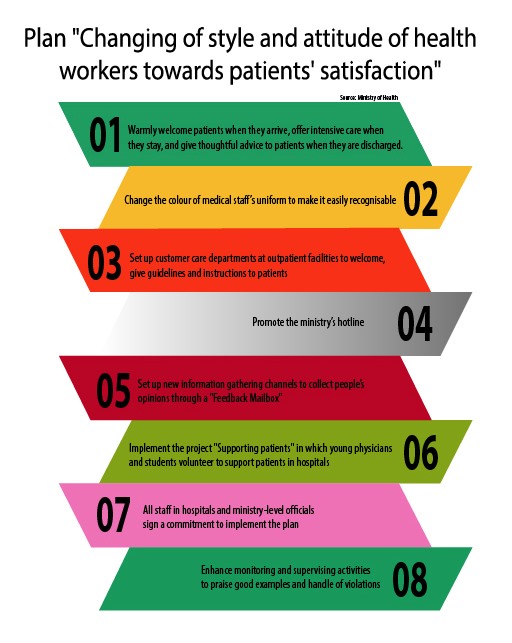

In June, 2015, the ministry initiated a plan called “Changing style and attitude of health workers towards patients’ satisfaction."

|

| Minister of Health Nguyễn Thị Kim Tiến |

A hotline number (1900.9095) was set up so citizens can report wrongdoings in the health sector. In 2016 alone, the hotline received 10,050 valid calls, of which 15.6 per cent were patients complaining about misbehaviour and irresponsibility of medical staff and just 1.2 per cent were about ‘corruption’.

In 2016, the ministry reprimanded 213 medical staff, stripped off rewards and commendations from 78, and dismissed 13 for violations.

Citing the Vietnamese proverb “Có thực mới vực được đạo” (or “a hungry belly has no ears”), Minister Tiến said the ministry “attached great importance to increasing incomes for medical staff.” Several measures are being taken to make this happen, she said. For this, healthcare service fees were being increased and financial mechanisms of public hospitals renewed towards self-financing so that they have more autonomy to decide the staff’s income, she said.

While increasing the income of medical staff is a must, the ethical aspect cannot be ignored, said Dr Phú of the Việt Nam Sports Hospital.

Doctors have to place their life-saving mission above everything else, he said.

“One can only love and follow a medical career if one is not too hung up on material benefits,” he said. — VNS

|

| VNS Infoghraphic Đoàn Tùng |