In the Spotlight

In the Spotlight

The Government has issued a decree, which, starting this month imposes punishments for littering, throwing cigarette butts and ash in non-smoking areas, urinating in public places.

|

| Infographic: Đoàn Tùng |

Linh Vân

HÀ NỘI - Around 8am last Saturday, my son and I were taking a break on the banks of Hồ Tây (West Lake) after riding around it on our bicycles. The sun was shining and we were enjoying the moment when it was rudely disrupted by a young couple.

The couple threw a bag of trash on the pavement, and its smell spread quickly, annoying many people who were doing their morning exercises. There was a trash bin not so far away, but they could not be bothered.

Littering is a very common occurrence in Việt Nam, including the capital city. Public spaces, including parks, are often a “free-for-all” space for throwing ice-cream sticks, wrappers, cans or water bottles. The habit cuts across all sections of society. People going around in expensive cars, often lower their windows and throw rubbish out. Bus and train stations are trashed all the time.

I decided to talk to the couple who’d just littered on the banks of the West Lake. Nguyễn Thị Huyền ,21, said they’d not known that there was a dustbin nearby. Besides, she said, there were sanitation workers responsible for keeping the streets clean and what they dumped was a small pack. It was nothing.

Huyền and many others do not realize that sanitation workers in Hà Nội alone have to deal with nearly 5,400 tonnes of household waste per day.

The littering habit is not only polluting the environment; it has also polluted the country’s image in the eyes of foreign friends.

Jonathan Meaney, from Canada, said the littering was disgusting.

“In my country, littering in public places is frowned upon. We think of cleanliness of cities and public places as the responsibility of the people. In a city like Hà Nội, which can be very beautiful, it’s shocking that people litter so carelessly and so often,” he said.

To deal with this worsening problem, the Government has issued a decree, which, starting this month imposes punishments for littering, throwing cigarette butts and ash in non-smoking areas, urinating in public places, and so on.

The decree has been welcomed by many people who say dealing with the “smaller” offenses can have a big impact, with violations attracting bigger fines, of up to VNĐ7 million (US$308).

In the latest case, last week, three taxi drivers were fined a total of VNĐ6 million by Hà Nội’s Hoàng Mai District police for urinating on pavements.

|

| Lawyer Đinh Ánh Tuyết, Managing Partner of IDVN Lawyers and Vietnam International Arbitration Centre Arbitrator |

Lawyer Đinh Ánh Tuyết, Managing Partner of IDVN Lawyers and Arbitrator of Vietnam International Arbitration Centre, said the fastest and most effective way to weaken bad habits and behaviours of people is to have strong laws with punishment that can serve as a deterrent.

Singapore is well known for the severe punishment it has for littering and graffiti, and this has proved effective in the island nation, which is famous for how clean it is. In Việt Nam, too, strict fines for riders without helmets and drunk driving have reduced violations in a very short time,” she said.

However, nearly a month since the new Decree took effect, there seems to be no difference, in littering or other practices.

On many streets in Hà Nội, like Tây Sơn, Nguyễn Lương Bằng in Đống Đa District and Trần Đại Nghĩa, Trần Khát Chân in Hai Bà Trưng District, trash is still dumped outside on the pavement by local residents.

Hoàng Ngọc Dung, a sanitation worker on Trần Đại Nghĩa Street, said people continued to throw rubbish on streets despite having dustbins nearby. “It makes our job harder,” she said.

Huyền, who dumped the bag of trash on the banks of the West Lake, said she did not know that littering is a punishable offence.

Toilets, dustbins

Many people have criticised the Government for not ensuring enough resources, including infrastructure and human resources, necessary for stricter laws to be enforced.

Vũ Thị Vinh, former General Secretary of the Association of Cities of Việt Nam, said a shortage of dustbins and public toilets was partly to blame for people’s littering and urinating in public places.

For example, there were just 340 public toilets in a capital city of up to six million people, she said.

The 1.5-km long Thanh Nhàn Street in Hai Bà Trưng District does not have a dustbin, so people end up throwing trash on the street, she said.

Head of the Hoàng Mai District Police, Nguyễn Hồng Thái, said the lack of human resources and necessary tools and equipment to record violations made it difficult for police to punish violators.

Other officials also welcomed the new law with stricter punishments, but said it would take time for it to be fully enforced.

|

| Head of the Việt Nam Environment Administration Nguyễn Văn Tài |

Head of the Việt Nam Environment Administration Nguyễn Văn Tài, said waste discharge had become an urgent problem and it required stricter laws to gradually change the bad habits of many people, he said.

Local authorities should be “creative” in finding ways to detect and punish violators, he said. "Apart from authorised agencies like the police, public participation and co-operation is necessary for disseminating and detecting violations," he said.

“Money collected via fines can be reinvested in improving infrastructure, including building more public toilets and installing more dustbins along streets.

“Residents who identify violators should be rewarded,” he added.

In tandem

Other people said several things have to happen together over a period of time for laws to become effective and cities to stay clean.

Administrative punishments should go along with people’s awareness and discipline, which should start from kindergarten onwards.

In Australia, for example, dusbins are located in many corners of schools, from kindergartens to universities, so students learn to deposit trash in the right places. Dustbins carry detailed information and images on the kind of waste that should be dumped in them.

Around ten years ago, Hà Nội implemented a plan to have dustbins for two kinds of waste, recyclable and non-recyclable. The plan failed because many people did not know how to classify the rubbish, which resulted from a lack of education on different kinds of rubbish and children not being taught about the importance of not littering.

|

| James Joseph Kendall, Founder of Keep Hanoi Clean |

James Joseph Kendall, Founder of Keep Hanoi Clean, which carries out clean-up activities every weekend, said he was glad to see the Government taking big steps to solve the problem of littering in the city.

“I think the new law will help, but I don’t think it alone will solve the problem,” he said. “I think education is the most important part of the solution.”

Starting a program in schools to make sure all children know the importance of being responsible when they throw trash would be a good start, he said.

Meaney said the care of public spaces required a cultural and educational change. “If Việt Nam wants to clean up its cities and the countryside, they need to encourage public participation,” he said.

Lawyer Tuyết said strict implementation of the law could have a strong impact.

“I think adequate human resources to impose penalties on violators is not the main feasibility factor for the law. If the punishment is meted out strictly, right from the start, without any concession or exception, the regulations will certainly take effect. People will become more self-conscious and careful about their behavior, and this will gradually minimise actions polluting the environment,” she said.

“In addition, the responsibilities of agencies and individuals in handling violations should be clearly stipulated to ensure its effectiveness. Obviously, the implementation of the new decree should be thorough and carried for a long time to be able to alter people’s behavior,” she said.

Vinh, former General Secretary of the Association of Cities of Việt Nam, also said participation of the community in keeping its surroundings clean would be a key factor alongside strong determination of the administration and improved infrastructure.

Once the attitude of people changes, it would help reduce environmental pollution on a larger scale, as factories and industrial zones. — VNS

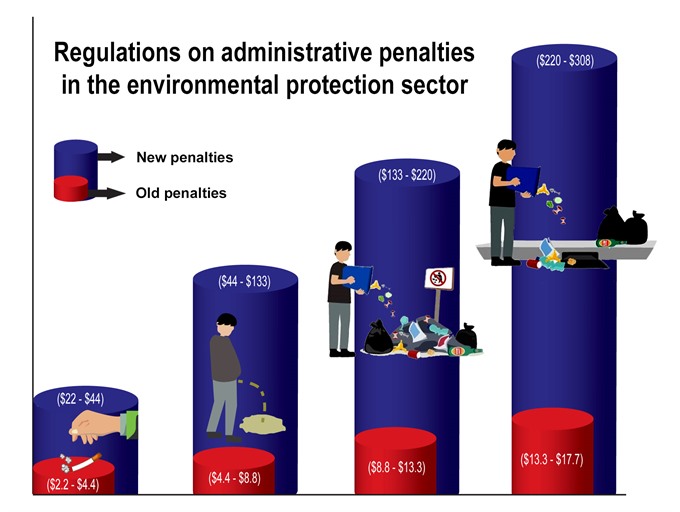

Decree 155/2016/NĐ-CP on administrative penalties in the environmental protection sector:

Types of fines:

- Between VNĐ500,000 ($22) and VNĐ1 million ($44) for throwing cigarette butts and ash in no-smoking areas, including shopping malls and residential areas.

- Between VNĐ1 million ($44) and VNĐ3 million ($133) for urinating in public spaces, including shopping malls, pavements and parks.

- Between VNĐ3 million ($133) and VNĐ5 million ($313) for littering in apartment buildings, commercial buildings or public places.

- Between VNĐ5 million ($313) to VNĐ7 million ($308) for littering on streets, pavements or sewage systems in residential areas.

- Other fines of between VNĐ10 million ($440) to VNĐ25 million ($1,100) to be imposed on violations such as trucks spilling building materials like sand on streets, failing to classify solid waste as regulated, and failing to transfer solid waste to functional units.

Who can impose fines:

- Chairman of the communal and district’s authority.

- Head of the communal, district police and head of provincial police.

- Police on duty

- Special inspectors, border and coast guards, customs officials and rangers.

Who can the fines be imposed on:

- Those aged 14-16 years old for intentional violations.

- Those aged over 16 years old for all violations.

The decree took effect on February 1, 2017.