.jfif) Opinion

Opinion

|

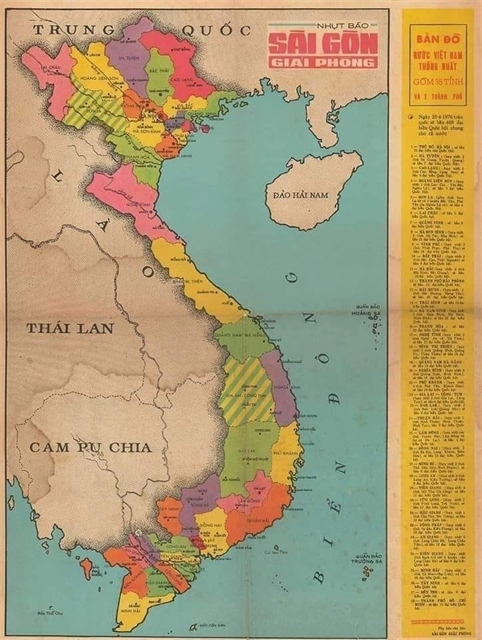

| A map of Việt Nam in 1976 with 38 provinces and cities that was published in the Sài Gòn Giải Phóng newspaper. Photo dantri.com.vn |

Discussing a proposed plan to merge provinces and reduce their number by around 50 per cent, historian Dương Trung Quốc speaks with the Dân Trí online newspaper about a past era, when Việt Nam's provincial structure closely matched today's reorganisation objectives.

Can you briefly outline Việt Nam’s historical experiences with provincial mergers and splits?

Throughout Việt Nam’s history, provincial mergers and splits frequently occurred, driven by changes in land area, population, natural conditions, and socio-economic circumstances. Adjustments to administrative divisions have always been essential for effective governance, a universal practice reflected clearly in Vietnamese history.

Việt Nam’s territory extends from north to south. Under the Nguyễn Dynasty (1802-1945), the country's territorial governance became notably stable. Following the defeat of the Tây Sơn dynasty and the unification of the country in 1802, Emperor Gia Long established Phú Xuân (modern-day Huế) as the capital. It was strategically positioned to facilitate communication between the northern and southern regions, given the era’s limited transportation and slow means of communication.

A significant administrative restructuring occurred under Emperor Minh Mạng, Gia Long’s successor, to create a stable governance model that remains a reference point for today's administrative planning. Minh Mạng reorganised administrative units, replacing the older ‘townships’ system with ‘provinces’ (tỉnh). At that time, Việt Nam comprised 30 provinces and the Thừa Thiên capital area. Provinces were further divided into prefectures, districts, and communes.

The historic division into 31 provinces aligns closely with today's proposal to reduce provinces by approximately 50 per cent, showing that maintaining a smaller number of provinces is not unprecedented in Vietnamese history.

What similarities exist between the 31-province structure under Emperor Minh Mạng and the current restructuring proposal?

During the Nguyễn Dynasty, Việt Nam had a significantly smaller population than today, and its society and economic activities were far simpler. Under the feudal system, villages funtioned as self-governing administrative units. Each village elected its own chief, who was the sole local official integrated into the state administration.

Yet, there was a common principle: the district and canton levels occupied strategic positions to gather village representatives and maintain connections with the capital. At the state level, the monarch’s most meaningful intervention was conferring spiritual legitimacy through royal decrees honouring village guardian spirits. Villages fulfilled their obligations by adequately providing taxes, soldiers and labourers, when required.

Thus, the traditional administrative structure was essentially simple, consisting of just two effective levels. District and canton administrations were mere transitional points, thinly staffed but strategically located for communication.

The most recent major wave of administrative mergers occurred in the 1960s. In the North, recognising that certain provinces were small in area and sparse in population, and considering the socio-economic conditions at the time, the Party and Government merged provinces such as Hải Hưng (Hưng Yên and Hải Dương merged in 1968), Bắc Thái (Thái Nguyên and Bắc Kạn merged in 1965), and Vĩnh Phú (Vĩnh Phúc and Phú Thọ merged in 1968).

After national reunification in 1975, the consolidation of various localities continued, reducing the number of provinces and cities to only 38 by 1976.

Entering the Đổi Mới period (1986–1990), the demand arose for smaller provinces to better facilitate economic growth and infrastructure development. Consequently, numerous provinces were divided, resulting in a total of 64 provinces and cities by 2004. Following the integration of Hà Tây Province, four communes from Hòa Bình Province and Mê Linh District (formerly part of Vĩnh Phúc) into Hà Nội in 2008, Việt Nam settled into the current structure of 63 provinces and cities.

Considering the historical context of provincial splits and mergers, what do you identify as the most significant difference in the ongoing administrative restructuring compared to past efforts, which will shape the direction of mergers?

Historically, the splitting of provinces generated momentum for regional development. Today, however, development demands have highlighted structural issues within local governance models, necessitating a more appropriate spatial development strategy. The administrative system clearly shows inefficiencies due to excessive bureaucracy, creating numerous bottlenecks in management and operation.

Meanwhile, infrastructure and information technology have advanced dramatically, making it entirely possible to oversee and manage extensive regions remotely.

I fully agree with streamlining the administrative system, including reorganising provinces, potentially eliminating district-level administrations and reviewing communal-level administrations. Along with reducing the number of administrative units, the overarching aim is to enhance their operational quality and efficiency.

As you've mentioned, the criteria and requirements for this administrative restructuring are now fundamentally different. They no longer simply revolve around population size, area or geographical regions, but instead require a new approach to spatial development planning. Has this also been a key point emphasised by the Communist Party of Vietnam's Politburo and the Secretariat?

Regarding the criteria for administrative restructuring, according to Conclusion 127-KL/TW, the Politburo and Secretariat clearly state that when developing proposals for provincial mergers, aside from considerations of population size and geographical area, we must carefully examine national master plans, regional and local planning strategies, socio-economic development strategies, sectoral development, expansion of development spaces and leveraging comparative advantages. These elements should serve as scientific bases and foundational principles for restructuring, fulfilling each locality’s developmental needs and aligning with the vision for the upcoming period.

I strongly agree with this set of criteria. As our leaders have pointed out, these principles reflect a strategic vision that extends hundreds of years into the future. Moreover, when merging provinces, we must carefully consider factors such as cultural and historical traditions, geopolitical and geoeconomic positions, as well aslocal identities. VNS