Life & Style

Life & Style

He shares his views about Chăm culture.

" />Poet and researcher Inrasara, a member of the 180,000-strong Cham minority, has spent his entire life researching its culture. The 60 year-old researcher pubished his latest book entitled Minh Triết Chăm (Wise Chăm culture) in mid 2016. He has published 40 books - including research books, poetry and novels - about the ethnic group that lives mostly in the central and south of Việt Nam, including Phan Rang, Phan Thiết, HCM City and An Giang cities.

He shares his views about Chăm culture.

|

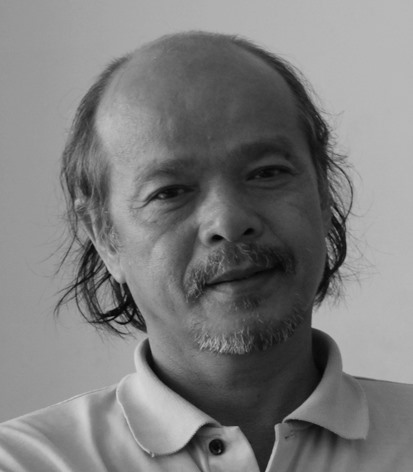

| Poet and researcher Inrasara.—Photo hanoimoi.com |

Poet and researcher Inrasara, a member of the 180,000-strong Chăm minority, has spent his entire life researching its culture. The 60 year-old published his latest book entitled Minh Triết Chăm (Wise Chăm Culture) in mid-2016. He has published 40 books - including research books, poetry and novels - about the ethnic group that lives mostly in the central and south of Việt Nam, including Phan Rang, Phan Thiết, HCM City and An Giang.

He shares his views about Chăm culture.

The Chăm people have a very rich culture. According to you, what is most remarkable in this culture?

It’s the language and literature of the Chăm people.

An old and collapsed relic can be restored by talented experts. However, how can experts restore the language and the Chăm literature, which reflect the depth of the soul of Chăm people?

Fourty years ago, I read a book written by a French researcher, Paul Mus. He said there is not much to say about the literature of the Chăm people, which could be summarised in 20 pages. I thought that an ethnic group which had its own script very early, since the 4th century, compared to other groups of Southeast Asia cannot be summed up in only 20 pages. I began to research Chăm culture and 30 years after going to live in HCM City I published my first book, which was honoured by the Peninsula History Culture (CHCPI) Centre of Sorbonne University.

Chăm literature, known for famous epic poems, reflects the soul of the Chăm. We can use it to decode the secrets of ancient Chăm architecture and sculpture.

What do you think of the way the literature of the Chăm is preserved given that books have disappeared or are at risk of disappearing?

I think it’s very important to teach young people about Chăm culture, about the important significance of preserving this culture and about the need for efficient solutions to preserve those old Chăm books.

The Chăm people are known as being very fond of learning. None of the Chăm are illiterate.

In the old days, the Chăm people used to preserve books by leaving them in bamboo baskets hung from the ceiling. Each month they used to worship the books (with a wine bottle and two eggs) and expose them to the sun to keep them dry. Books which were not worshiped and not read for a long time were called “fallow” books.

Books are made to be read. But the many young people of today do not appreciate the books. I know an old man who has three baskets of precious books. But his sons do not like them. According to a traditional belief, a family that wastes those books and lets them become “fallow” risks falling sick and has to make an offering to spare themselves a run of bad luck. They also have to throw them into the river. It’s one of the reasons why books have gradually disappeared.

Why have the Chăm managed to preserve their cultural identity over such a long period despite the influence of different religions and time?

The Chăm are the only minority ethnic group in Việt Nam that does not live in the mountains.

They have lived together with the Viet (or Kinh) people for 200 years but their culture was not assimilated. They used to believe that there are four steps in life. First, learn from teachers; Second, become a master of a household (get married); Third, live in the forests and leave everything behind; and the last, live a free life among the trees and under the sky.

Nowadays no one follows these four steps. But husbands and wives remain very faithful to each to each other. I have lived in the Chăm community for 60 years but have rarely seen divorced couples.

Do Chăm festivals remain authentic or have they been commercialised?

Luckily, many of those festivals remain authentic. For example, the Rija Nưga festival which is held in April to welcome the New Year and the Ramuwan festival held in September to worship ancestors.

However, some have become quite commercial. The Kate festival, held at the Po Klaung Girai temple in October, has become the festival of all people. A parking lot and an exhibition house were built and the serene ambiance of the Po Klaung Girai temple disappeared.

Previously, this temple used to open its doors three times a year to welcome visitors. Buddhist priests entering the temple used to burn candles for only one hour each time, so the pink colour of the bricks of the tower was preserved. Now the tower is often open to tourists who burn a lot of incense, which turned the bricks black. I criticised this time and again but nothing changed. — VNS