Life & Style

Life & Style

The award-winning documentary Công Binh-The Lost Fighters of Viet Nam, highlighting the history of Vietnamese peasants conscripted for France during World War II, has been shown in Hà Nội.

|

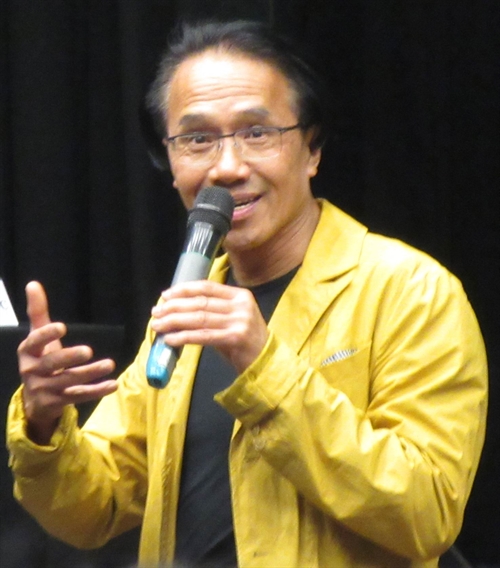

| Film director: Lê Lâm. |

The award-winning documentary Công Binh-The Lost Fighters of Viet Nam, highlighting the history of Vietnamese peasants conscripted for France during World War II, has been shown in Hà Nội.

Directed by Lê Lâm, the film is about 20,000 Vietnamese young men who were forcibly recruited in French Indochina during World War II. They were shipped to France to work in weapons factories, replacing French workers sent to the front to fight against Nazis.

Mistaken for soldiers, they were stuck in France after the 1940 defeat. They pioneered rice cultivation in the Camargue. During the Occupation, these workers – called “Công Binh” – lived at the mercy of the Wehrmacht (unified armed forces of Nazi Germany) and lived like pariahs. Although wrongly accused of betraying their native Việt Nam, they were all strongly committed to Hồ Chí Minh, rooting for Independence in 1945.

Vietnamese-French director Lê Lâm talked with Bạch Liên about the film.

Why did you decide to make this film?

More than 70 years have passed since the tragic years which the công binh lived ended. Many French and Vietnamese people never heard of their stories. I was determined to make this film. It portrays a page of French-Vietnamese history that is often forgotten.

In 1939, a great number of Vietnamese families had their members who were sent to work in France.

The role of an artist and film director is to wake up forgotten stories. When the young generation knows more about the history of the country, they can create a better future.

To make the film, I found 20 witnesses and survivors: 10 living in France, 10 living in Việt Nam. They talk of their daily lives under colonialism, when they worked under extremely difficult conditions for a miserable salary. Living in camps and prisons, they were given almost nothing to eat. Many died of serious diseases.

Luckily, some of the surviving công binh who stayed in France after the war succeeded in life and earned international reputations, like painter Lê Bá Đảng.

In 1952, 1,500 công binh returned to Việt Nam after the war. But they were considered traitors to the country. Many Vietnamese believed the công binh helped the French during the war. For a long time, I thought the công binh were traitors, too.

Your film features many water puppet scenes showing farmers living in Việt Nam talking about family members forced to go to work for France. Why did you use water puppet art in the film?

The 20,000 Vietnamese men conscripted to go to France were around 18 years old and illiterate. They did not know what to expect. They were like puppets, manipulated by the French colonial authorities. This made me think of using water puppetry in the film.

Water puppetry is a unique Vietnamese art, created by rice farmers. So I tried to transform water puppetry into cinematographic language.

I made 14 puppets for the film.

How did French audiences react to the film?

The film was first screened in France three years ago. It was shown in 300 cinemas throughout France. It was highly acclaimed in France and won several prestigious prizes.

In each cinema where the film was shown, I met one or two children or grandchildren of công binh who went to watch the film. One woman about 50 years old saw the film three times and she travelled to different regions to watch the film.

She is the daughter of a công binh. But she didn’t know anything about her father’s past. She was born in France. At four years old, her school friends mocked her and called her Annamite. She cried and ran home to ask her father why her classmates were mocking her. But her father could not answer. He didn’t know how to explain why he was living in France.

After she saw the film, she understood her father’s past and her origins. She said: “Now that I know about my origin, my grandchildren will grow up well…. Even though they are French citizens, they cannot forget they are Vietnamese”.

It took me three years to make the film, including several trips to Việt Nam to meet survivors and witnesses. The film lasts 120 minutes. But I filmed 120 hours of material. Watching the filmed scenes, I cried. I couldn’t imagine that the công binh had experienced such difficult times.

Part of the modest funding for the film came from French producers. But I spent my own money to make the film because it is very important to me. I had to make it, no matter what it cost.-- VNS