Economy

Economy

HCM CITY — Việt Nam was the fastest growing digital economy in ASEAN last year, with the potential to become the second-largest one by 2030. Thanks to its large consumer base and rising number of internet users, it is not hard to understand the potential in its digital economy, according to a HSBC’s experts.

Based on the e-Conomy SEA report, a series of sizeable digital investments in ASEAN recently attracted our attention. The region has become more tech-savvy in the past two decades, with Việt Nam clearly standing out.

That said, challenges remain. For one, how to increase Việt Nam’s digital literacy remains a priority, as Việt Nam has been lagging behind regional peers. Encouragingly, the National Digital Transformation Programme is an example where the public sector seeks to play an active role to facilitate the digital transformation of the economy. Meanwhile, how to secure the additional energy necessary to fuel the momentum is another challenge, evidently shown in the case of data centres.

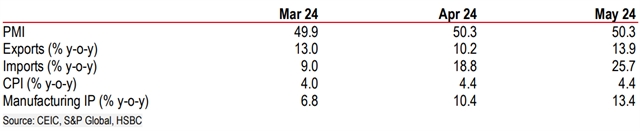

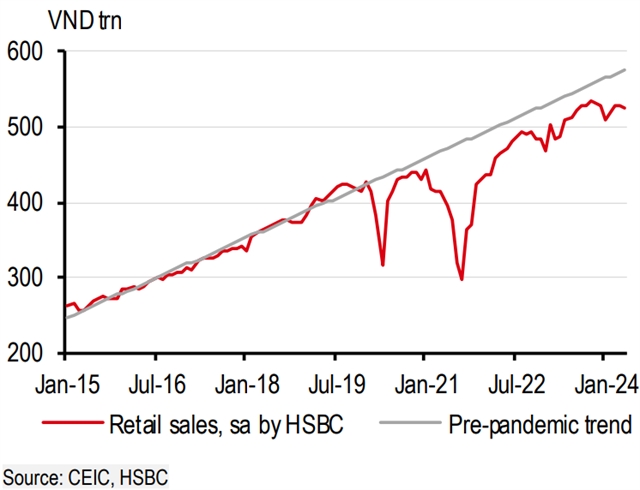

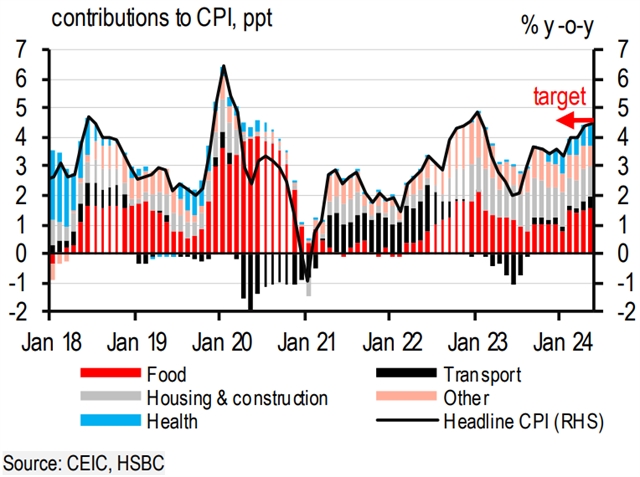

Heading towards the end of 1H24, Việt Nam remains on track for an external-led recovery. That said, it is still not broad-based, with the electronics sector taking the lead. Meanwhile, the domestic recovery continues to lag behind, with muted monthly retail sales performance. Outside of growth, inflation continued to hover close to the 4.5% ceiling in May. The performance was rather a mixed picture in the food and energy segments, warranting a close watch in the near term.

Table 1. Summary of key recent economic indicators

|

Chart 1. Việt Nam has one of the highest digital potentials in ASEAN

|

Becoming ‘digitally fit’

A flurry of digital-related investments has been taking place in Southeast Asia. Microsoft recently announced a number of investments in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. In Vietnam, Alibaba plans to construct a data centre to accommodate rising digital demand. Clearly, with much focus on tapping into the rising digital economy in Vietnam, we take a closer look at some of the fundamentals at play.

With a population of over 100 million and a working age share of close to 70%, we see the strong potential for Vietnam’s digital consumption. According to the e-Conomy SEA 2023 report, Vietnam was the fastest-growing digital economy in ASEAN with impressive growth of 20%. Measured by gross merchandise value (GMV), the country has the potential to become the second-largest digital market in the region by 2030, just after Indonesia (Chart 1). We expect the expansion to be led by a rapidly developing e-commerce ecosystem, supported by a rising consumer base.

But it is not just the demographic tailwinds – Việt Nam’s rapid rise in internet users also helps expand its digital market. Almost 80 per cent of Việt Nam’s population now use the internet, thanks to smartphone ownership more than doubling from a decade ago (Chart 2). However, despite the considerable growth in internet users, the application of digital technologies in certain areas has lagged behind. According to the World Bank’s 2021/22 data, Vietnam lagged behind Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia in terms of using non-cash payment methods (Chart 3), although efforts to transition to digital payments have accelerated since then.

Chart 2. ASEAN has become more internet-savvy

|

Chart 3. Discrepancy between internet and digital payment use in ID and VN

|

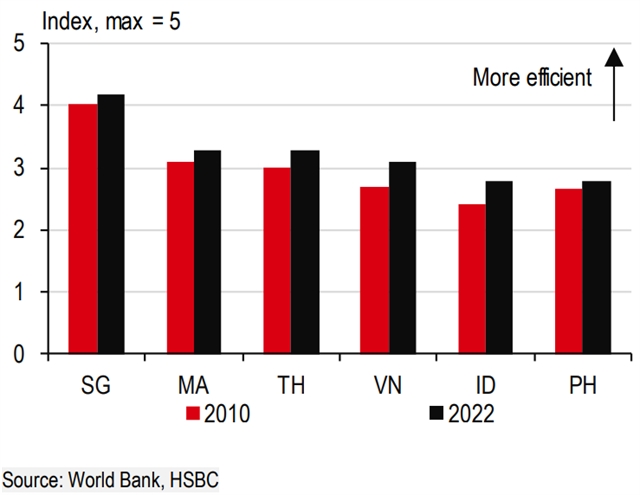

Chart 4. Customs clearance efficiency has improved over the past decade

|

Chart 5. …but more can be done to raise trade efficiency

|

Meanwhile, digital transformation has more room to run in areas beyond consumers. Trade, for example, is still relatively paper-based. This can risk imposing additional costs and delays, serving as a bottleneck on trade flows. Although increasing use of the National Single Window, an online platform to process trade documents between firms and the government, has led to material improvements in customs clearance efficiency (Chart 4), some hurdles remain.

For example, the use of digital signatures remains limited, meaning some procedures still need to be handled by paper. As shown in Chart 5, alternative measures of digital integration within trade suggest further room to transition to paperless paperwork.

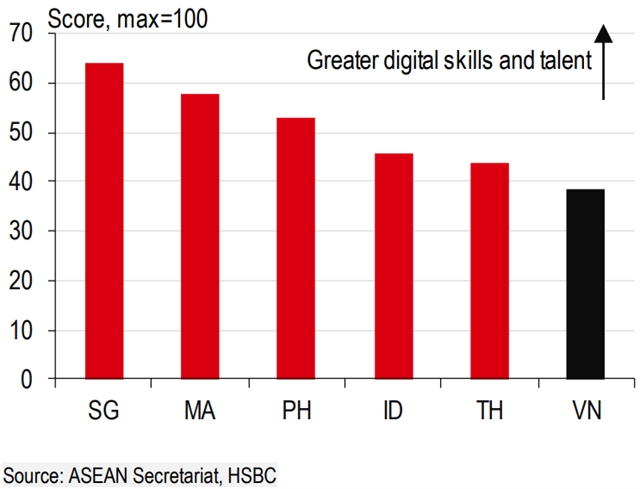

That said, part of the challenge stems from lagging digital literacy of the population, which has hindered the adoption of digital tools and constrained their effective use. In terms of digital skills and talent, Việt Nam lagged its peers (Chart 6), limiting the upside from digitalisation.

Encouragingly, the government is well aware of these challenges, and has been playing an active role to facilitate the digital transformation of the economy. In accordance with the National Digital Transformation Programme through 2025 with a vision to 2030, Việt Nam aims to build the three pillars of digital government, digital economy, and digital society.

The government has correspondingly laid out a number of ambitious targets in recent years, including handling all administrative procedure applications online by 2030.

The national strategy opens up opportunities in a wide range of sectors. In particular, digital literacy is relatively low among the rural population and in the agricultural sector. At the end of 2021, there were more than 27,000 agricultural cooperatives, but only c2k applied ‘high-tech’ and digital technology in production. Furthermore, these groups typically still depend more on traditional financing methods.

Chart 6. There is scope to further raise digital literacy (2021)

|

Chart 7. Digitalisation is a key business priority for firms in ASEAN

|

While state-led initiatives to drive rural digitalisation have spurred progress in building a digital economy, it is important to note that private businesses can also play a role in accelerating the transition. For example, Grab conducted training workshops for over 800 cooperatives to help farmers learn about digitalisation and related business opportunities.

Another important consideration is how to secure the additional energy needed to fuel the momentum. A contributing factor is Decree 53, originally introduced in 2022, which requires firms to store data locally. Future proliferation in the volume of local data suggests more data centres being built, as was likely a partial factor in Alibaba’s decision to construct a data centre locally. This highlights the linkage between growth in the digital economy and the availability of energy, of which the latter has already seen some challenges. Power outages last May and June were estimated by the World Bank to have costed 0.3% of GDP, particularly affecting manufacturing firms. As electricity demand looks set to expand further, expanding and improving Vietnam’s energy supply and infrastructure will become more important.

All in all, digitalisation brings both opportunities and challenges to Vietnam. In order to leverage its favourable demographics and achieve its digital ambitions, investments need to be channelled into not just new areas such as artificial intelligence (AI), but also foundational areas such as digital education and traditional infrastructure. In fact, this drive is not just happening in Vietnam, but in ASEAN as a whole. According to a recent HSBC survey, more than 40% of surveyed businesses operating in ASEAN rank digitalisation as a top priority (Chart 7). Therefore, active dialogue and partnerships between the public and the private sector can help accelerate these developments to prepare for a more digitally fit population.

May at a glance

Việt Nam’s recovery in the external sector continued in May. Export growth jumped 13.9% y-o-y, beating market expectations (HSBC: 9.5%, Bloomberg: 10.6%). Similar to previous months, consumer electronics took the lead, accounting for 60% of growth (Chart 8). The encouraging sales performance and outlook for Samsung’s new flagship, the Galaxy S24 series, is likely providing some uplift.

In addition to electronics, expanding market access is also helping Vietnam to buoy certain agricultural shipments. For example, Vietnam’s durian exports to China almost doubled in the first four months of the year, largely eating Thailand’s market share in China.

Chart 8. An upturn in the electronics cycle continues to fuel Việt Nam’s export growth

|

Chart 9. Challenging supply conditions have pushed up Robusta coffee prices

|

Chart 10. Vietnam’s coffee exports up in terms of value, but not volume

|

However, it is not rosy for all agricultural products. Coffee, which Vietnam is famous for, saw a surge in international prices (Chart 9). While coffee exports, on a value basis, continue to expand, the volume fell markedly (Chart 10). Indeed, officials recently noted that crop output this year is expected to be the lowest in four years, a reflection of the increasing relevance of climate trends and the impact of El Niño on ASEAN’s agriculture sector.

In addition, ongoing disruption to trade, such as from the Middle East, is also weighing on certain shipments. Textiles and footwear continued to track sideways, likely attributable to its higher export exposure to Europe and its related trade routes. Meanwhile, some port congestion in Asia also warrants close monitoring, as it looks to continue in the near term.

While exports growth hit double-digits, so did import growth, and even more so. Imports rose 25.7% y-o-y, well beating consensus (HSBC: 19.3%, Bloomberg: 20.0%). Despite a broad-based pick-up, energy imports rose notably, likely reflecting the government’s efforts to address energy supply amid challenging conditions in hydropower generation due to adverse weather.

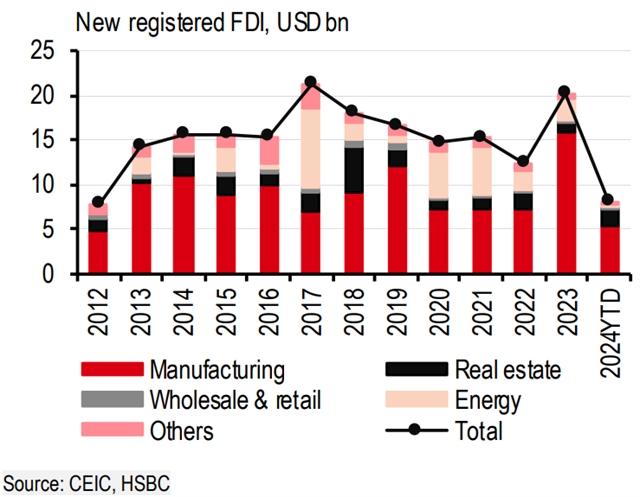

Long-term business interest also showed little sign of slowing. FDI remained well on track to sustain the momentum seen in 2023. Newly registered FDI grew double digits YTD, with incremental flows centring on the manufacturing and real estate sectors (Chart 11). As a testament to Vietnam’s attractive investment for a range of manufacturers, Pandora, a jewellery brand, has started construction of a US$150m factory in Bình Dương.

Chart 11. FDI flows are well on track to see

2023 levels

|

Chart 12. There are some signs of stalling in the domestic recovery

|

Chart 13. Inflation still hovered close to the inflation ceiling in May

|

Chart 14. Favourable base effects from energy prices have faded

|

Despite the positive external recovery, the domestic sector saw some softening signs. Retail sales growth, measured on a monthly seasonally-adjusted basis, moderated in May (Chart 12), and the number of monthly international tourists cooled to c1.4 million. While Vietnam’s annual target of 17-18m tourists for this year looks well within reach, it is facing intensifying competition as regional peers have been racing to introduce more visa-free schemes.

Lastly, inflation warrants a close watch in the near term. Headline inflation was flat at 4.4% y-o-y in May, hovering close to the State Bank of Vietnam’s (SBV) 4.5% ceiling (Chart 13). The breakdown revealed a rather mixed picture. While rice prices dropped on a m-o-m basis, pork prices pushed up the overall food price momentum. Although oil price momentum dropped (Chart 14), a hike in electricity prices, which is typically reflected in the CPI with a one-month lag, reminds one that Vietnam is easily exposed to global commodity volatility.

What is partly driving the rise in import prices is a weaker VNĐ. Currency developments led by a higher-for-longer US interest rate environment have led the SBV to be more proactive in managing FX pressures. The SBV has been implementing a number of measures outside of adjusting its refinancing rate, such as through more flexible open market operations (OMOs). While the risk of a near-term hike in the refinancing rate rose, we expect the SBV to hold the policy rate steady as the economic recovery is still in its nascent stages – a delicate balancing act indeed. — VNS