.jpg) Sunday/Weekend

Sunday/Weekend

April 30, 2018 is the 43th anniversary of the full American pullout from Việt Nam. The assumption has been that after the Americans left, there was a terrible bloodbath in [South] Việt Nam, but history should get both sides of this story correct. There was no bloodbath.

|

| A tank rolls into Saigon on April 30, 1975, while curious people chat with the newly arrived soldiers. — Courtesy photos of Claudia Krich |

By Claudia Krich*

Thursday (April 30, 2015) was the 40th anniversary of the full American pullout from Việt Nam.

We hear a lot about those who fled and the suffering they endured.

The assumption has been that after the Americans left, there was a terrible bloodbath in [South] Việt Nam, but history should get both sides of this story correct, now, 40 years later. There was no bloodbath.

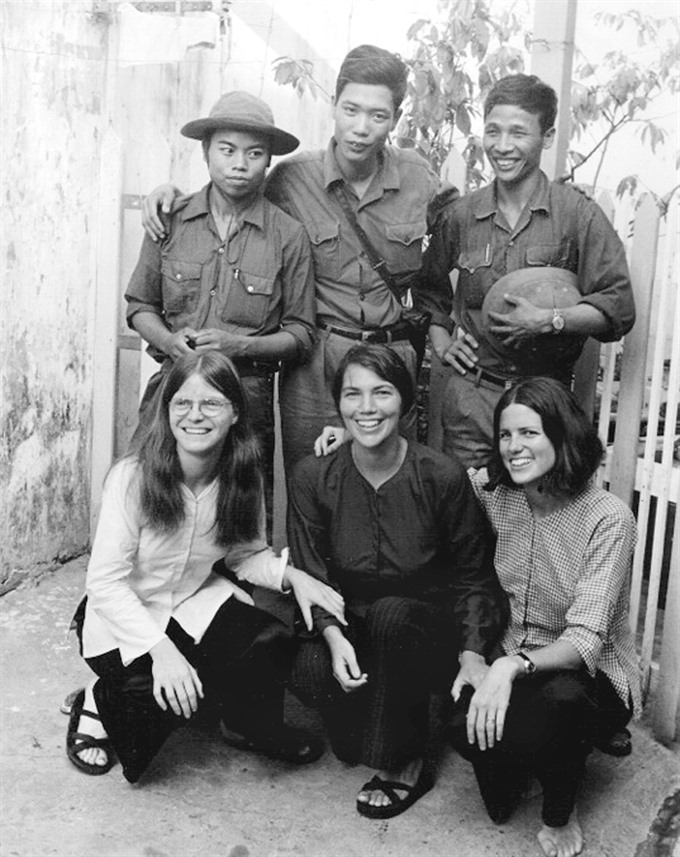

I was one of a handful of Americans who stayed in Saigon while the rest were fleeing and helping panicked Vietnamese friends and staff do the same at the end of April 1975.

The propaganda had been extensive and effective in Saigon that the conquering North Vietnamese and National Liberation Front soldiers would maim, murder, mutilate and destroy. But they didn’t.

I had been in Việt Nam two years already, and stayed in Saigon until July 1975, thus witnessing first-hand the change of power and the first few months after the American-supported South Vietnamese yielded full power to the National Liberation Front and the North Vietnamese, (also called simply the Vietnamese).

We lived in Quảng Ngãi, a poor town near Mỹ Lai in central Việt Nam, where we directed a civilian rehabilitation programme and hosted visiting journalists and officials. During the time we lived there, the area was controlled by the South Vietnamese during the day, and by the Liberation Front (locals against the Americans and South Vietnamese) during the night.

As the South Vietnamese Government began to crumble, we fled to Saigon. But we learned later that the transition had been peaceful. In fact, the Liberation Front had entered the town 24 hours after the South Vietnamese officials had already left.We decided not to leave, and to see the change in Saigon for ourselves. So when the Americans were putting people on helicopters at the embassy, we stayed.

Of course, there was danger. It was a war. There were bombs, rockets, artillery and random rifle fire by scared soldiers in the last days. America also was testing other less conventional weapons until the very end.

A few weeks before the end of the war, the South Vietnamese dropped an American CBU 55 bomb on civilian Vietnamese, killing everyone and every creature in range that breathed oxygen. The United States also tested agent orange and white phosphorus on the Vietnamese population.

We dropped carpet bombs and cluster bombs and, of course, planted hundreds of thousands of land mines.

And there was the C5A aircraft that was packed with children, but unbalanced, that crashed in mid-April 1975, killing 138 people.

Saigon’s population had been mostly shielded from the war until the end, while those who lived outside the city suffered for years and years. In April 1975, the danger and the war reached Saigon and the residents panicked.

We spent the night of April 30 in a little house on a little alley.

|

| A truck carrying North Vietnamese soldiers, foreground left, is stuck in a huge traffic jam on May 1, 1975, as everyone was out on the streets following the American pullout. |

|

| South Vietnamese soldiers arrive on May 1, 1975, at Van Hanh University in Saigon, where they discarded their uniforms and guns, then left as ordinary civilians. |

|

| Claudia Krich, kneeling at left, is one of three American women and 12 Americans altogether who stayed in Vietnam after the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. Here, they pose with three North Vietnamese soldiers who were eager to have their photo taken with American women. "They couldn’t imagine they were meeting American women," Krich remembers. "They had cameras and took lots of pictures. This picture was taken in our little alley where we lived." |

The next morning, the streets of Saigon were jammed with relieved people, out sightseeing and curious to meet the arriving soldiers.

Many of the arriving busloads and tanks carrying the soldiers were stuck in traffic. We saw people throw flowers and cigarettes to the arriving soldiers. Everyone was taking pictures.

South Vietnamese soldiers in Saigon discarded their uniforms, turned in their weapons at improvised collection centres, and joined the crowds.

North Vietnamese soldiers camped in the city parks, washing laundry and hanging it on clotheslines strung between trees.

They all spoke the same language, of course. In fact, many families that had been split between the north and the south met again in those first few days, after decades apart. The soldiers met each other, took pictures, and shared stories.

We spent the next few months being taken for Russians as we lived normal lives in Saigon.

We observed the new government organising to recover from war; improve general health care, housing and education; increase access to water and electricity; and “re-educate” the South Vietnamese high-level government officials who were still there.

But there were no firing squads; there was no murder, no torture.

The new Government was committed to reconciliation as the only way to unite the country and make progress.Of course, many Vietnamese fled then and in later years.

The money-poor new Government immediately had to deal with a large number of refugees streaming in from Cambodia where the Khmer Rouge had taken over.

They had to deal with antagonism and fighting with China, and they had to be careful in their relationship with Russia not to alienate others.

The United States embargo caused tremendous suffering.

Việt Nam, once a major rice producer, had needed to import rice during the war due to the destruction of rice fields. It took a lot of time and a lot of land-mine removal before they could return to growing their own rice. It is true that rich Saigonese lost most of their wealth. Much of that wealth had been acquired during the American war and through contacts with Americans.

The post-war effort tried to reconstruct the country and to redistribute wealth. But the new government tried to avoid retribution and there was no killing of enemies. They even wanted to be friends with America, despite the long, deadly war.

And now, America is enriched with many new Vietnamese-American citizens, and Việt Nam is enriched with a peaceful relationship with America. — The Davis Enterprise/VNS

*Claudia Krich, a longtime Davis resident and retired teacher, attended a KVIE screening in Sacramento last week of the documentary “Last Days in Vietnam” and was moved to write this essay, first published in 2015 by The Davis Enterprise. The documentary rekindled memories of the unique experience she and her husband Keith Brinton shared there 40 years ago. From 1973 until July of 1975, Brinton and Krich co-directed a civilian rehabilitation programme and hosted visiting journalists and officials in Quãng Ngãi, near Mỹ Lai, in central Việt Nam. Brinton also worked there from 1966 to 1970. In April 1975, they did not leave Saigon with all the other Americans. They stayed and saw what happened.