Op-Ed

Op-Ed

In just several hours on Wednesday, two explosions constantly occurred at the same place in a village in the northern Bắc Ninh Province’s Yên Phong District, killing two people, both of whom are children, and injuring eight others, all are nearby locals.

|

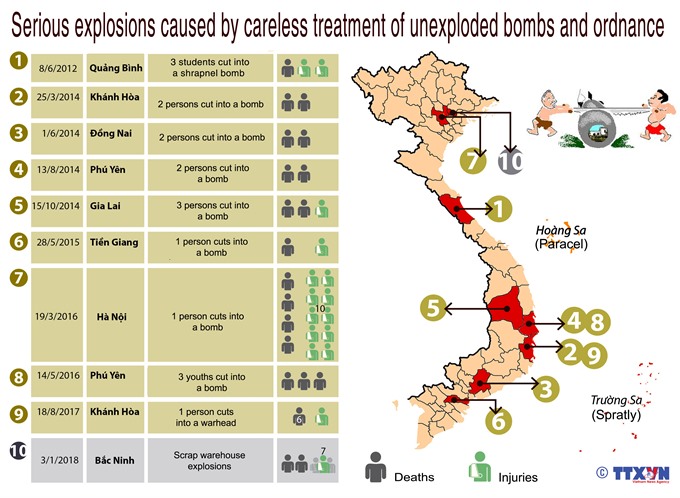

| VNA/VNS Infographic |

by Mai Khuyên

A deep crater is all that remains where a building once stood.

An explosion the likes of which the nation had not seen since the American War days obliterated the building, killed a baby boy and a five-year-old girl, injured at least eight people, destroyed several houses, unroofed several others, and scattered live ammunition over a very large area.

Wednesday’s blast in Bắc Ninh Province’s Quan Độ Village in Yên Phong District has shaken the nation, and provided yet another grim reminder that the deadly legacy of the war has not left us.

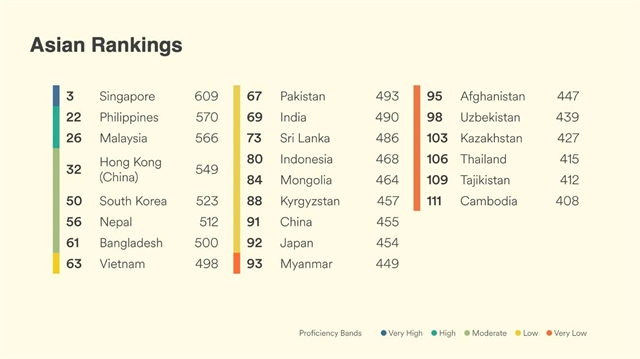

More importantly, it has also reminded us, graphically, that even fundamental safety precautions are often not being taken when dealing with the issue of unexploded ordnances that litter large swathes of our land, killing and maiming people with depressing regularity (see infographic).

The explosion happened at a scrap warehouse that had, officials say now, illegally stored military weapons. The collection of unexploded ordnances to sell as scrap is not a new vocation in the country, and it is not the first, or second, or third time that tragic accidents have happened.

To cite just a few examples, on March 19 last year, an explosion took place in the Văn Phú residential quarter of Hà Đông District in Hà Nội, killing five and injuring 10 others. Another explosion occurred in Đức Bình Tây Commune, Sông Hinh District, the central province of Phú Yên, on May 14 the same year, killing three people.

It is not a cliché, but a truism that individuals, the Government and society have to act together to prevent such tragic accidents.

Articles and photographs of the Bắc Ninh explosion have reached far and wide, and they emphasise how urgently an alarm should be raised on the lack of awareness and loose management of explosives at local levels, particularly the illegal storing and trading of military weapons as waste material for recycling.

Obvious follow up actions have been taken: a criminal probe into Nguyễn Văn Tiến, 54, who owned the scrap warehouse, local administration being asked to work with the Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of National Defence to identify the cause of the explosion, and so on.

But we cannot afford to ignore some other obvious facets of this issue.

Soon after his arrest, Tiến told the the police that he had bought seven tonnes of old cartridges from a staff member of the Technology Centre for Bomb and Mine Disposal under the Army’s Engineering Command since January 2016, to disassemble and sell as scrap. The ammunition was stored at the warehouse where the explosion occurred.

Seven tonnes!

Such a large quantity of ammunition being bought and sold could not have escaped the notice of both local and military authorities, surely?

Tiến has been remanded to custody to investigate the illegal storing and trading of military weapons under Item 3, Article 304 of the 2015 Penal Code. Did he know of this regulation? Or was it a deliberate violation?

As we look for answers to all these questions, we cannot escape one conclusion: this disaster, including the death of innocent children, is not just one man’s action, it is a collective failure that implicates all of us.

Last year, Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc instructed concerned ministries to adopt urgent measures to prevent and limit accidents caused by bombs and mines left over by the wars. He also asked Committee 504, tasked specifically with overcoming the aftermath of bombs and mines left behind after the war, to advice ministries on any legal changes needed to enhance national management of the issue.

But we do not have to look far for what can be done.

‘Not rocket science’

“It’s not rocket science,” said Chuck Searcy, an American War veteran who has been on a mission for almost two decades to help deal with the scourge of UXOs and rehabilitate their victims.

He cited a heartening success story that should give all of us hope and the determination to do what is needed.

“In Quảng Trị Province, Project RENEW for 15 years has maintained a steady campaign of public knowledge and information about the risk of tampering with unexploded ordnance.

“The practice of scrap metal collecting, attempting to dismantle or defuse old bombs, has dropped dramatically. And the rate of accidents, injuries, and deaths in such explosive incidents has been reduced nearly to zero.”

Zero is the target we have to aim at, seriously.

Referring to ordnance related accidents that have been happening all over the country, Searcy said, “they do not happen in isolation.”

He noted that few other provinces, including Bac Ninh, have launched risk education programs in schools, communities and among the general population.

Highlighting the extent of the problem, he noted that the “lurking danger remains from more than eight million tonnes of ordnance dropped by the US during the war, a lot of which did not explode at that time.”

“The RENEW model that has been created in Quang Tri Province, in close co-operation with Norwegian People’s Aid, Peace Trees, Mines Advisory Group, Golden West, the Vietnamese military and provincial government, is the platform that we hope will keep Viet Nam safe from such incidents in the future.

“This model eventually, we hope, will be expanded and introduced into other provinces that are contaminated by bombs and mines,” Searcy said.

Amen. We have no excuses left for the next such tragedy. — VNS