A short story by Vũ Thị Huyền Trang

|

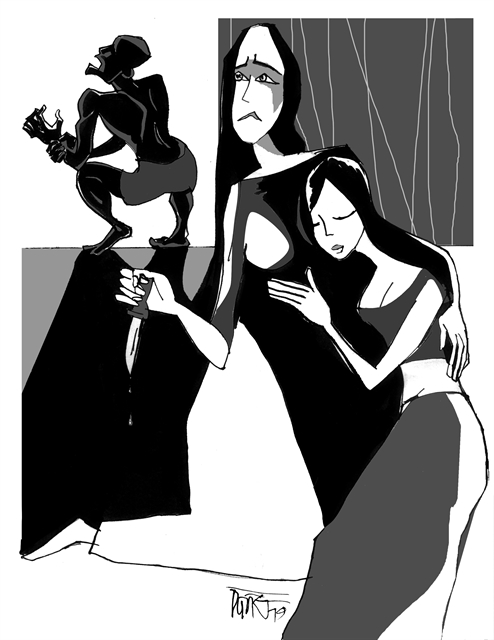

| Illustration by Đỗ Dũng |

A Mother’s Heart

Mai lay with three men who gave her three babies. Hón was born out of her marriage with the first husband who was a bus driver. That marriage lasted for a day. The morning after their wedding night, the bus company called Mai’s husband to work in an emergency. He lost control of his bus when it went down a slope. The bus crashed into an abyss while carrying 30 passengers. When Mai learned the news, the wedding roses were still fresh as they perched on top of her wedding bed canopy.

A few weeks after the funeral, all of Mai’s in-laws gathered around her asking, “Have you felt anything yet?” Mai answered with bouts of nausea and requests for sour tamarinds. Her husband was the sole son so everybody watched Mai chew the tamarinds nosily with happy expectations. When Hón was born, the little girl dashed the whole family’s hope. Mai’s father-in-law sat up all night smoking. The following morning, his hair was white. “Well, a daughter is okay,” he said. “She’s still our flesh and blood.”

During the three-year period in which Mai observed her widowhood, she didn’t dare look in the mirror to see her face which had faded with each sunrise. Her wrinkled fingers knitted as she lay in bed at night. One winter morning, Mai couldn’t stand the prospect of growing old inside her husband’s bedroom any longer. She took her daughter and left. As Mai sat waiting for a train, Hón frolicked around plucking wild flowers. On the train, the little girl smiled as she watched the trees glide by the window. Mai felt as if they were aboard the arrow of time. In just the blink of an eye, Hón turned 18. Her face looked like the moon, beaming with graceful curvature. The girl was so breathtaking that every time she passed back and forth before her third husband Phi’s eyes, Mai shuddered.

Hón often wore skin-tight crop tops that revealed both her waist and navel. Her shorts were also skin-tight, baring all of her rosy tender youthfulness. A few times Mai reminded her daughter to dress properly, especially when Phi was around. Yet every time Hón replied, “I’m not you in your days, mom. My girlfriends all dress like me. Phi isn’t a stranger. He’s like a father to me.” Mai wasn’t sure if Phi wanted to be Hón’s father. Phi wasn’t her legal husband. He had sought her out in her tiny smelly boarding room merely out of lust. Though there was a child between them, Mai doubted if it could tie him to her.

Phi was a Vietnamese-American. At 20, he fell in love and got married to a Vietnamese-American woman. After more than 30 years of marriage, they had birth to three daughters. The oldest was already 35, had got married and made Phi a grandfather many years before. Though he had a handful of children and grandchildren, Phi still yearned for a son. Outwardly he often boasted that he came from a civilised, progressive and open-minded country. He criticised Vietnamese men for being conservative, patriarchal, violent, and cowards. At almost 60 years of age, Phi still looked quite young. Others might mistake him for being just over 40. He was tall, handsome and expensively-dressed. He raced his motorbike around with his head held high and paid restaurant bills with dollar bills, which was enough to sweep any woman off her feet. Mai was fooled by those appearances. Or to be more accurate, in her eyes then, Phi belonged to another world, standing taller than all the men around her. He too looked tall beside her, a withering mother of two.

Every lunar October Phi returned to Việt Nam to observe his father’s death anniversary. He had a bunch of brothers and sisters. Three lived in America, one in Canada, and three in Việt Nam. Phi’s father had passed away a few years before, leaving behind his mother who was still clear-headed at 90. Every night when Phi slept around with girls at his hotels, the old woman with her conical hat would seek him out and create an uproar. She knew exactly where he was. She would go to the right den and point her finger at some particular lover and scold, “Are you after his money? What a slut. I’ll drag you back to your parents.” Phi laughed and gave his mother a few boxes of ginseng:

- These are my gifts to give you strength to keep on chiding us.

- I know you want to sleep around to have a son. But you’re destined to have only daughters. You won’t have your way. Or if you do, your son may not be yours. So stop fooling around with these greedy women. I’ve married you off once and only have one daughter-in-law and three granddaughters. I won’t accept anyone else.

- I’ve married myself off, not you. So you don’t want to have a grandson to lead your funeral? I want to have a son here so that he can take care of our ancestor worshipping ceremonies.

- I don’t need to be worshipped after I die. Just cremate me and scatter my ashes into the river. Don’t fool around or you’ll destroy your family.

Phi didn’t say anything, because his mother wouldn’t have understood him. He only confided his deep secrets in some potential lover he was wooing for the moment. He did so the first time he got drunk and told Mai about his unhappiness.

- My wife turned frigid after she gave birth to our third child. She didn’t let me touch her. We slept separately.

- Why didn’t you take her to see a doctor?

- She refused. She didn’t care about my feelings anymore.

Mai was so infatuated with Phi that she decided to give him a child even when she was still married to her second husband, a sailor. Phi slept with Mai then returned to his family in America. After one year of traversing the sea, the sailor came home to see his wife’s belly bulging. He was thunderstruck. What a tramp. A slut. A whore. Those words were hurled at Mai by others, not by the sailor himself. For his part, the sailor didn’t say anything. He only made a fist with his hands, which made Mai fear sooner or later he would strangle her and her baby to death. For half a month afterwards, Mai didn’t dare to look up at him during meals. At last he spoke: “If no man claims this baby, I will.”

Yet Mai had become fed up with her husband. She wanted to take this opportunity to leave him. Ever since they got married, never for one day had she felt free from care. When she was pregnant with their own son, little Thản, the sailor didn’t even go to work. He would go to his ship for a few months then took half a year off to lie idly at home. Mai didn’t have enough money for daily expenses. Less than a fortnight after giving birth, she carried her newborn on her back and went out to work. Hón was only five then but already had to work as a waitress by serving customers food, cleaning the tables and chairs, and washing the dishes in freezing temperatures to help her mother run a street food stall. Once in a while little Thản would cough violently from his mother’s back after inhaling too much burning honeycomb charcoal. Hón would spread some jute bags on the pavement and huddle herself to sleep. At the time, Mai’s husband would be drinking with some neighbours. At noon, he would return home and demand, “Where’s lunch?” After growing tired of the land, he would leave for the sea for a long time without once phoning to inquire after his family. Mai got into debt and had to sell the house. So with the third man, she planned to give birth and follow him. She figured that the sailor would be responsible for the boy and Hón would work part-time to pay for her own tuition. As for the new child, Phi had promised to help Mai take good care of it.

Unfortunately, the child Phi had anxiously expected wasn’t male. He was disappointed and turned cold for a while. Yet after little Mít could speak, her carefree baby talk drew her father back. Every feature on her face took after her father’s too. Phi called his daughter every day on Facebook. Mai didn’t do anything but stayed at home to take care of her youngest one. Phi sent her $1,000 every month. With food, rent, and electricity bills, it didn’t amount to much. Mai didn’t have much left to pay for Hón to go to college, or for Thản to continue to high school. She wanted to work but Phi objected, saying, “Don’t make me lose face!”

Mai didn’t have any alternative but to rely on Phi. But Phi was no longer the man she had once admired. Or to be more accurate, he had always been himself, only she had let her imagination run wild. He could be generous to strangers but was stingy with her. He made careful calculations so that every penny was accounted for. For one whole year, Mai didn’t dare buy herself any new clothes. After Phi was caught cheating, his marriage in America fell apart and his company went bankrupt. He went back to Việt Nam to brood about a comeback. Though he got a reputation of staying in Việt Nam to take care of his aging mother, he spent all day at Mai’s place. The boarding room, which was only 20 sq.m, grew even smaller with so much stuff and so many heads. It was seldom lit up with sunlight and seemed to be soaked in the damp, sour, stingy smell of moss, cat poo and mice. After having lived most of his life abroad, Phi sometimes felt like vomiting as he crawled into this barbaric nest. His friends asked, “Why don’t you buy them a house?” Phi sneered, “Not yet.” Mai knew it was impossible. She was only a breeder for hire and couldn’t expect more.

- You don’t even know how to breed. If only you gave me a son, I’d give you everything.

As Phi said these words, his eyes glanced at every step Hón took. The room was littered with stuff, making Hón feel like she was stranded as she walked. She was looking her best, full of youth and life. Her breasts blossomed, her lips curved, her skin shone. Sitting next to her, even her mother smelt spring. Once in a while, her stepfather Phi pretended to compliment her nonchalantly, “You look prettier day by day, Hón.” Mai followed Phi’s eyes which seemed glued to her daughter’s butt and bumps. The whole family had only one bed and Phi asked to sleep over every night. Thản had been sent to live with Mai’s parents. The mother pushed her other kids to one corner of the bed to avoid touching their stepfather. Yet one morning when she woke up, Mai was startled to see Phi hugging Hón.

- Don’t you think shit honey. I’m a liberated Western man. Between your daughter and me, there is only fatherly love.

- It’s different in Việt Nam. You’d better watch out.

- What a vulgar woman.

Hón stood outside her mother’s worries. The girl often boasted innocently that her stepfather Phi had given her money to buy a new dress, to go to the cinema, or to have her hair cut. Mai didn’t know what to say. If she told the truth, she feared her daughter would treat her stepfather with contempt. But she couldn’t let Hón go on being innocent forever. Mai wanted to snatch her family from Phi’s claws. But what about little Mít? Without him, Mai didn’t know how to feed her children. And she couldn’t lose Mít to Phi either.

Mai tried many times but still couldn’t tell Hón her fears. When her friends dropped by, Hón boasted lightheartedly that her stepfather loved her very much. These days, Phi stuck to Mai’s house without returning to his mother. Only when his drinking buddies called did he crawl out of the damp room. When he came home, he was often drunk and asked Hón to play chess with him. As Mai went to the market, cooked, or did anything else, she felt on fire. As Phi was playing chess, his eyes kept hovering around Hón’s revealing chest. Mai planned to send her oldest daughter to the city to learn bakery. The girl had dexterous hands and dreamed of running her own little bakery shop. She must push her daughter away, the sooner the better, Mai thought. Her nest had turned into a tiger’s den.

Hón was yet to move out when something happened. One night, she was startled out of sleep by a shriek that seemed to tear apart the darkness. Phi darted out of the room with a knife stabbed right through his hand. Blood dripped and trailed his footsteps. Hón looked dazed, wondering what was happening. Mai shut the door tight and told her children to “get back to sleep”. Then she knelt down and wiped away every bloody stain left on the floor. Phi hadn’t expected to be stabbed by a sharp knife when his fingers crept onto Hón’s breast. Mai had been hiding a knife under her pillow for some time. When she slept, the pointed knife had often scratched her nape…

Translated by Đỗ Linh