Born in 1951, Vĩnh Quyền is an established writer in Việt Nam's literary circle and has authored 18 books. His journalistic background as Central Region Head Office Editor of Lao Động (Labour) newspaper in Đà Nẵng for many years gives his offerings a real-life edge under worldwide issues, yet tangled in traditions and age-old customs.

Quyền writes in both Vietnamese and English. His English language novels include Debris of Debris and Inside Infinity.

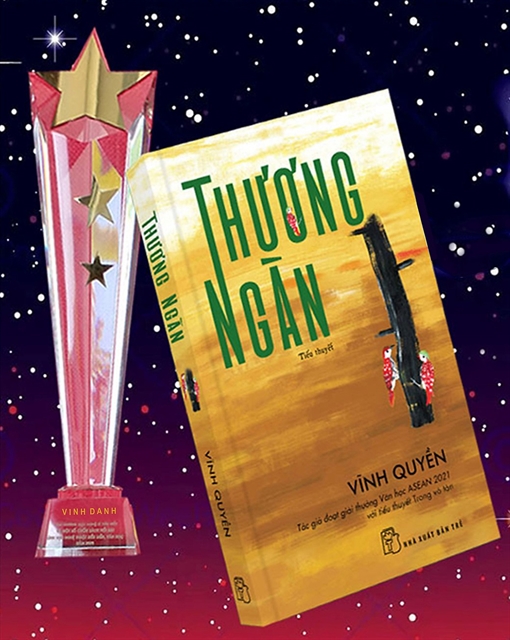

Việt Nam News presents an exerpt from his latest book, Thương Ngàn (Heart for Forests), his fifth novel. It touches upon a genre of eco-literary theme in Việt Nam, and the author's vast knowledge of the traditions, customs and life of a jungle paints a cinematique and vivid picture.

|

by Vĩnh Quyền

The two-week survey in the golden oak forest had ended. We held a team meeting by the campfire. I said “team” out of habit, but at that point – if you didn’t count the dog that always followed me — it was just Katy and me. Katy was an Australian PhD student, passionate about wildlife research. Two days earlier, the head of the Vietnamese delegation had left for Hà Nội to catch a flight to South Africa for a conference on combating rhino-horn smuggling.

Y Bham, the elephant jockey, had gone upriver at noon to find Y Tun and prepare for the return trip to Lak District. Whenever the group stopped, elephant Y Tun was allowed to forage freely after his front legs had been loosely chained.

There was nothing to discuss about the failed survey. We had walked through most of a large forest identified on satellite imagery, and until the last day of the programme we had no luck spotting a red wolf. Katy’s three camera traps had also recorded nothing. As for me, I was just a guide and a seasonal contract translator, not involved in the scientific work or administrative matters.

The golden yellow of the Australian woman’s hair, the earthy yellow of the dog’s fur, and the lemony yellow of the moonlight flickering in the campfire combined in my mind into a picture of wild yellow tones. My fingers flexed slightly, but I remained almost motionless, the camera resting in its leather bag on my lap. I knew I wouldn’t capture the photograph I had in my head – everything that looked sparkling and beautiful before my eyes would feel different after a click.

That thought led to another: I wondered whether Katy had kept or deleted the clip from the camera trap taken two days earlier.

Y Bham had moved one of the camera traps in a final attempt to confirm evidence of the red wolf, but had forgotten to tell Katy. He aimed it toward the stream and hung a salt bag on a tree near the bank, where he had found footprints indicating animals had come to drink.

Then, the next morning after breakfast, Katy and I checked the camera’s results for the previous day. We were both shocked. The camera had captured Katy bathing in the stream – naked, illuminated by the moonlight.

Embarrassed, Katy was speechless. I quickly turned off the screen, said we still hadn’t spotted the wolf, and left the tent to smoke a cigarette.

“If I get the chance to come back to Việt Nam, I hope to have Kiên’s assistance – Kiên has been exceptional these last two weeks,” Katy said gratefully, setting the tone for the meeting.

I nodded and absently twirled my fingers around my moustache, hiding a half-smile. Katy suddenly flushed; her eyes flashed with suspicion, as if she guessed what image of her I had been holding in my mind.

Pulling me back to the so-called meeting, Katy cleared her throat and said, “No language barrier at work, so you’re the kind of person international survey teams need.”

I changed my position and lit another cigarette before replying, “I can’t help with this survey. I’m sorry.”

A rare expression of joy appeared on the delicate but austere face of the workaholic blonde. She continued, “Just because we haven’t encountered red wolves doesn’t mean they aren’t here – we’ll persist. And with Kiên’s help, I’ve gathered crucial information about Việt Nam’s dipterocarp forests.”

Unsure what to say, I smoked in silence.

Katy shifted to something more personal. “Where did Kiên learn English?” she asked.

“At university,” I answered briefly, thinking, No one can know what that language means to me.

The campfire gradually died down, growing as soft as a silk ribbon fluttering upward. The flapping wings of a large sleepy bird in the nearby bushes and the high-pitched chorus of crickets, geckos, and cicadas around us reached their peak, amplifying the quiet between us.

Katy’s expectant gaze prompted me to clear my throat – I realised I needed to say something.

To begin, I told her I had learned English in the first days after returning to civilian life, following five years as a reconnaissance soldier. A grenade fragment had lodged in my head – a souvenir from a drug smuggler across the Vietnamese–Cambodian border.

“It’s still here,” I said, tapping the back of my head. Her expression of helpless concern moved me and made me more willing to tell my story. I continued.

The first thing I saw when I woke was a white shape sitting at the foot of the bed, murmuring words like a prayer. For a moment, I thought I was dead, forever twenty-three. Then the figure slowly came into focus, and I realised I was still alive in the military hospital; the silhouette was a young nurse in uniform.

She put down a book and, meeting my open eyes, exclaimed. In a brisk voice she told me I had been in a coma for more than a week – long enough that she could watch over the living corpse that was me and still study for her English exam in night class without being reminded. No one at the hospital believed I would recover.

“What did they call my condition then?” I seemed to ask myself.

Katy blurted out one word: “Clinically dead.”

I went on: a week later, the nurse showed me photos from the closing ceremony of the English course. I froze when I saw the teacher – a woman with long hair past her back.

Katy leaned forward. “A lover?”

I nodded and continued. As soon as I could walk again, I signed up for the English class. I was eager to see my high‑school sweetheart, and my mood was as tense as it had been before the shooting. But in the eyes of that only‑child woman, I was merely a pleasant memory of a youth everyone experiences.

Still, I could not resist the pull of the past. I accepted her invitation to dinner, feeling as though villagers were reconnecting in a strange city. After that, I occasionally visited her home. While waiting for her to finish cooking, I would play chess with her husband.

After I finished that English course, the medical assessment results arrived: I left the army as a seriously wounded soldier. Leaving behind the rainy season and the sad love affair in the Central Highlands, I travelled south to seek change. My memories of the forest led me to the Đồng Nai Forestry University.

Somehow, the English night class had steered me toward a programme taught in English. Thanks to that, after graduating, I passed the exam and won a full scholarship for a research programme in Australia. A year later, however, I had to put my studies on hold to return home for medical treatment.

I paused to light another cigarette. Katy watched me smoke in silence, concern evident on her face. Suddenly she reached for the cigarette in my hand, brought it to her lips, exhaled the smoke, looked into my eyes, and dropped the rest into the burning embers. A small flame flared, then died out as if nothing had happened.

“Kiên has smoked more than ten cigarettes tonight,” Katy said, her tone a mix of admonishment and accusation.

I sat with my hands on my knees, not touching the pack of cigarettes anymore. My reaction was ambiguous; I was not sure whether I agreed or disagreed. Still, there was a pleasant surprise for me: even a wild man could soften when cared for and could yield to the gentle, imperious power of a woman.

Katy steered the conversation to her concerns. She had noticed me tirelessly walking through the woods for the past two weeks and hoped I had overcome the difficult period with my health. I confided in her that the problem was more mental than physical. Although I had been feeling almost normal lately, the doctors warned the illness might return because its root lay hidden in my memories – or perhaps it was the memory itself that defied human intervention.

Suddenly, I found that I was opening up, haltingly, about something I had never told anyone and had never expected to disclose.

Katy shook her head slightly. “Memories? I’m not sure I grasp what Kiên is trying to say.”

I stopped, feeling as empty as a car that had run out of fuel. Still seated with my knees bent, I stared at the pack of cigarettes resting on the dry firewood.

Katy reached in, took out a cigarette, clumsily lit it, took a quick drag, and handed it to me.

“Thank you, Katy,” I said, and I looked into the Australian woman's eyes as if searching there for an answer to the question that had just arisen in my mind: should I avoid it or lead Katy into my memories – those bleak memories?

Those clear, bottle-green eyes suggested that Katy had something in common with me: she lived in the woods more than at home and was someone who could share with and understand me better than anyone else.

The dog snuffled just as I was about to continue. It had been lying with its muzzle on its front paws, then sat up, eyes bright, nose tilted up toward the source. As if the scent in the air wasn't yet certain, it tensed slightly, but still stood there with its long tail curved upward.

"She hasn't had a litter, has it?" Katy changed the subject.

I nodded, knowing she could read the condition of an animal through its external appearance.

“I heard you call her Lài. I know Vietnamese names for people and animals usually carry meaning,” she continued.

“What you say is true, though in this case I’m not sure. She was given the name by her previous owner, a Mông man from Lai Châu who had recently moved to the Central Highlands, when he sold her to me as a three-month-old puppy. I can only guess that ‘Lài’ with a falling tone comes from ‘Lai’ with no tone, meaning ‘hybrid’, since she’s part dog and part wolf.”

“This type of breed is especially rare because, as you know, wild dogs are now nearly extinct,” I added.

The dog wagged its tail anxiously as it looked out over the stream. It flared its nostrils, then stiffened in a state of suspense.

“She’s probably just picked up Y Tun heading this way,” I said.

Katy studied the dog, then shook her head, “I think she’s caught the scent of a male. If you look between her hind legs, you can tell. It’s the end of spring after all; breeding season’s underway.”

Not looking at Lài but Katy, I thought to myself that even though I wasn't an expert, I could guess she hadn't done that in a while.

Swiftly shifting away from my inappropriate thoughts, I told Katy that during the press conference in Buôn Mê Thuột, most attendees were non‑zoologists and had been startled by the phrase “the dusk wolf” in the Vietnamese translation. Some even asked if I had made a mistake.

“Really?” Katy grinned. “The red wolf is most active in the early morning and evening. That’s why scientists use that image to describe them.”

“I suppose even scientists can be romantic.” Then, I asked, “What about you?”

"Oh, I'm not sure." Katy chuckled softly, leaned in, and retrieved a bottle of wine from her backpack.

We sipped in silence until Katy repeated her question about the memory issue in my health, which caused me to interrupt my research program.

Perhaps my response may have been somewhat vague, but it was unavoidable.

I chose forestry as my college major without much thought. It was a direct link to my childhood – the son of a forest-plantation contractor – and my experiences as a border-guard scout. One could say I was as familiar with the Vietnamese–Cambodian border forest road network in the Central Highlands as the palm of my hand.

Studying forestry allowed me to reconnect with that environment. The most delicious meal I ever had was unseasoned wild meat, grilled to a perfect half-raw, half-cooked state. The most exquisite drink I have ever tasted was an ethnic wine distilled from tree roots grown above two thousand metres, perpetually dusted with frost. I couldn't say when my aversion to socialising began; I felt at ease and secure when I was alone in the forest.

In other words, I didn't just choose a career for the future; I chose to continue living in the world of my past. Everything would have been fine if it had ended there.

For a long time, I enjoyed calling myself "the son of the forest". But I failed to understand — and even misunderstood — the essence of the "mother of the forest". Through silvicultural science texts and documentaries at university, my cognitive and emotional relationship with the natural world gradually changed.

That shift led me to a graduate research programme in Australia, majoring in nature conservation. During fieldwork, drawing on my background as a former border-guard scout, I was assigned to a team combating criminals who illegally hunted and trapped wild animals.

After a week of intense operations, I received distressing news from my younger brother back home: my father had been arrested while leading a group armed with chainsaws into the yew reserve.

Once widespread since the Ice Age, yew trees now survive only in southern China, Laos, and Việt Nam, and they are endangered. Việt Nam is home to more than 200 yew trees, some over 700 years old, concentrated primarily in Ea H'leo and Krong Nang districts, Đắk Lắk Province.

The mastermind behind the illegal activity confessed he had travelled from Hà Nội to the Central Highlands to harvest yew, believing it had medicinal properties that could cure various diseases, including cancer. My father admitted his involvement, saying he did it out of necessity to fund my mother's cancer treatment.

That night, I felt a mix of blame and pity for my uneducated father, who had worked tirelessly all his life. I also felt anger at myself for being ineffective and unable to help my parents and younger sibling.

Around four in the morning, a sharp pain erupted from the old wound that contained a grenade fragment lodged in my cerebral cortex. The surgeons had advised against removing it because of the risk of paralysis. Believing the pain was stress-related, I took a paracetamol, tried to calm myself, and repeated, "Everything will be fine," until sleep overtook me.

The following day, instead of taking sick leave, I joined the team in the forest on a mission to rescue trapped animals. The morning progressed smoothly until the headache returned, starting mildly but intensifying. The sun's glare hurt my eyes; my steps faltered, and I lagged behind the team, eventually collapsing under a baobab tree, exhausted. After drinking water and taking another paracetamol, I continued to tell myself, "I am the forest's protector," until I lost consciousness.

Uncertain how much time had passed, I faintly saw Tâm, my sixteen-year-old brother, emerging from the gumbi tree by the stream, cautiously setting a wire trap. I had taught him that skill. He had to replace me in hunting wild animals to improve the family's meals after I left to join the army.

At my border-guard unit, the food was more plentiful and better than at home. At first, I liked canned food, but it soon made me sick. So I went into the forest – not with a wire trap but with a CKC sniper rifle – looking for fresh meat for my platoon. I was so good at this that people called me “hunter”.

Let's go back to my delirium in the Australian baobab forest:

I cupped my hands like a loudspeaker and shouted, "Tâm! Listen to me, stop..." but only choking sounds escaped my chest or mind.

Not hearing or seeing me, Tâm quietly vanished into the gumbi bush after completing his task. Despite the agony, I pushed myself to rise, intending to dismantle my younger brother's trap. I left the baobab tree's shade slowly, but collapsed face down and abruptly awoke from the delirious illusion.

While waiting for emergency treatment, I lay on the dry ground in the hot sun, remembering when I returned home from the border-guard unit and was happy to see meat on the table without my mother having to spend money at the market. Going to college changed my awareness: birds became no longer just flying pieces of meat but rare species worth protecting. I could not accept eating birds and animals listed in the Red Book.

I had a bitter memory. During a family meal, I said to Tâm, "Stop using wire traps. It's simple, yet it can catch anything from tiny squirrels to giant elephants. In other words, it's a blind trap; no species is spared. Setting a wire trap is unintentionally committing a crime."

Tâm and my father bowed their heads and struggled to finish the plate of grilled wild birds while my mother and I ate vegetables. She did it for me, not because of my words. The peaceful family reunion suddenly fell apart.

At that moment, I paused, unable to continue. My emotions overwhelmed me; I looked up at the starry sky to hide my tears – a rare sight for me.

Katy's trusting blue eyes and the fading campfire in the darkness coaxed me out of my shell, prompting me to reflect on my life with a mix of indifference and sorrow and to put my thoughts into words.

After a period of silence and bewilderment, Katy drew closer, running her fingers through my hair and gently touching the scar on my head where a wound still lingered, triggering painful memories.

"It's all right, it's all right..." Katy murmured, then added, "We can't erase the painful memories of the past, but love can create new memories for the future, soothing the old ones."

The chirping of nearby crickets swallowed my thanks.

We separated when a long, boisterous howl suddenly rose from upstream.

Katy gasped, whispering, "The dusk wolf!"

The dog trembled, hissed, and then, following the male scent, bolted away.

I stood and moved my feet.

Clinging to me, Katy said urgently, "Let them be free..."

* * *

Katy’s love for me was the driving force that brought me back to Australia to continue my unfinished research programme.

About a year later, I witnessed the “Black Summer”. Massive fires ignited across many forests in New South Wales and quickly spread to other regions. Every day, the television was filled with images of burning woodlands; the landscape seemed to be ablaze. Birds and animals desperately searched for escape routes, their motionless bodies captured by reporters’ lenses.

I could not help but shed tears as I watched. An estimated one billion wild animals died in the fires, and billions more suffered serious consequences. The smoke – laden with PM2.5 particles, including carbon, sulfur, and nitrogen pollutants – threatened small creatures up to 50 km from the fires. The scientific community expressed deep concern that many native plants and animals may have been lost in this catastrophic event.

Five of my classmates and I formed a volunteer team. We equipped ourselves with protective gear, learned firefighting techniques, and registered with the local government to serve the community. But even though the wildfires were at their peak three weeks later, we were still not deployed. In late November, I couldn’t bear to sit idly by and watch the wildfires burn on TV, so I decided to go. I rented a pickup truck and loaded it with cold water, Neosporin for burns, plastic containers, towels, and some milk. I decided to go on the mission without Katy, who was two months pregnant with our first child.

Eight hours later, the horror began to dawn on me. From the golden afternoon sun, my truck entered the shadow of a red-grey cloud that covered part of the sky. An hour later, I drove through the burnt forests. The fire had been extinguished, leaving behind a thick carpet of unstable ash and dust, with sporadic columns of smoke lazily ascending. The sensation of descending into a solitary hell brought conflicting thoughts: I wanted Katy by my side, and at the same time I was glad she wasn't on this deadly trip.

Occasionally, I saw people helping surviving animals that had made their way to the roadside. I continued driving until I reached the first active blaze. A team of professional firefighters looked exhausted from more than two months of fighting an unequal battle with the god Vulcan.

When they noticed my protective clothing and gear, the team leader approved my request to join. He handed me a hose, but I shook my head. Carrying my backpack, I explained why I had come. He was stunned for a second, then understood. The brigade had to work hard to block the fire’s path while there were still many lives in the burning forest that needed saving.

The captain directed three team members to spray water at one location. I rushed along the temporary waterfall that reduced the terrible heat and pushed me to the other side of the fire line.

I was interested in watching Environment Minister Sussan Lei speak on ABC television about the attitude needed when rescuing wildlife during the national forest fire disaster. She emphasised the equal importance of all species. I didn't have to consider that equality, because I met only koalas – a species I love. I imagined that other agile creatures like kangaroos and deer might have had the chance to flee to unscathed parts of the forest before the fires spread.

The endearing clumsiness of the koalas seemed to limit their escape. Instead of fleeing far from the flames, they sought refuge by climbing the nearest trees and curling up in vulnerable balls. I helplessly watched these beloved creatures cling to the trunks, burning and falling.

I climbed each tree, removed every living koala, wrapped it in a wet towel, carried it beyond the fire line with the aid of sprinklers, and handed them to the fire team before swiftly returning. At first, I quietly tallied the saved koalas: “Three… five… seven…” Yet the scorching heat eroded my composure. It culminated when a flaming branch snapped and struck my left leg. A firefighter rushed me to the ambulance, which had arrived roughly ten minutes earlier.

I was surprised when he placed me in the car’s trunk alongside the koalas I had rescued. They gathered around and looked into my eyes, making me believe they recognised me. Their small, blistered, bloody paws clumsily tried to touch me gently, tending to my wound in their way. In their unique manner, they conveyed gratitude and a desire to care for me.

In that instant, I was glad to have the chance to count the koalas several times, like a poor person endlessly counting his modest possessions – also the common property of this earth. “Thirteen… thirteen…” My tears flowed, burning my blistered face.

In that moment, Katy’s words whispered in my mind once more, like the chorus of a lyrical ballad:

“We can’t erase the painful memories of the past, but love can create new memories for the future, soothing the old ones.” VNS

, MOSTI, YB Tuan Chang Lih Kang Minister of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI), Tuan Fabian Bigar, Secretary General of the Ministry of Digital, and Norman Matthieu Vanhaecke, Group CEO of C)