Features

Features

Vietnamese lacquer painting, or sơn mài, has become a precious and unique artistic craft over the course of thousands of years. Its global reputation is to be fostered now the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism has officially approved a project on building and publicising a national brand for Vietnamese lacquer art by 2030.

|

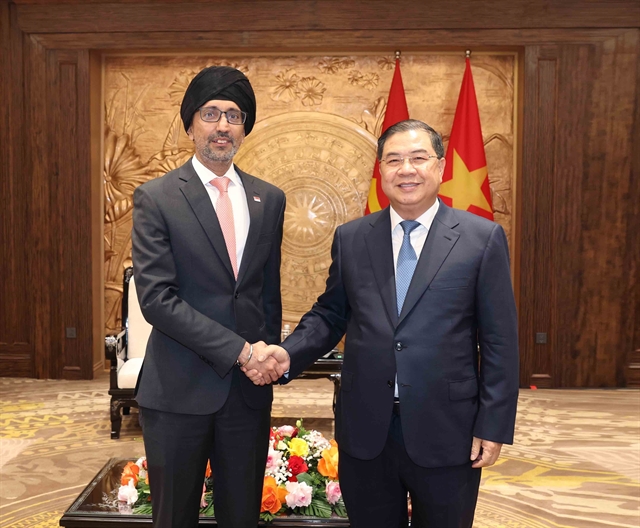

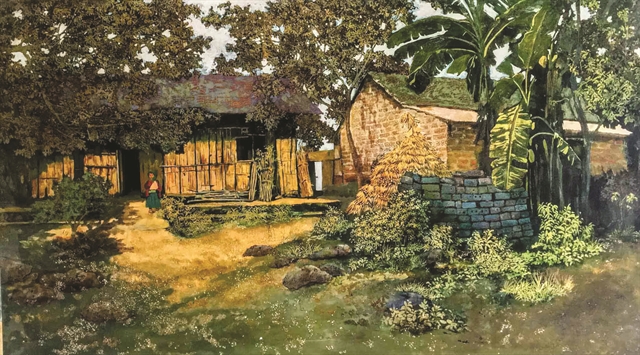

| SKILL ON SHOW: One of Chu Viết Cường’s lacquer paintings. Photo kenhnghethuat.com |

By Ngọc Anh & Mai Phương

Vietnamese lacquer painting, or sơn mài, has become a precious and unique artistic craft over the course of thousands of years.

Its global reputation is to be fostered now the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism has officially approved a project on building and publicising a national brand for Vietnamese lacquer art by 2030.

The project aims to boost its development and growth as well as present the land and people of Việt Nam to international friends via cultural exchange activities.

A report from the ministry's Department of Fine Arts, Photography and Exhibition notes that the project has been in place since last year and has primarily focused on preparations for surveying and collecting opinions from experts, researchers and management officials.

|

| KEY CRAFT: Villagers focus on the lacquer painting process in Hạ Thái Village in Hà Nội’s Thường Tin District. Photo thuongtin.hanoi.gov.vn |

Department Director Vi Kiến Thành touched on lacquer painting’s long history in Việt Nam. Boasting unique artistic features, the traditional craft has the conditions needed to become a distinctive art genre of Việt Nam and contribute to boosting tourism and socio-economic development.

Under the project, relevant agencies and localities are to focus on developing logos and identifiers for Vietnamese lacquer paintings and on issuing standards relating to materials and creative style.

Investment in growing sơn (lacquer) trees in the northern province of Phú Thọ and the promotion of lacquer production in Hà Nội’s Hạ Thái Village will also be given focus.

A host of events will be held to promote the brand name of Vietnamese lacquer works, including international and national festivals, workshops, seminars, exhibitions, and tours introducing and exploring the traditional craft.

Books, documents, and videos on the art form will also be published to promote sales as souvenirs.

An international lacquer art festival will be held every two years to promote the local brand name in global markets.

Training in creating traditional lacquer artworks is also a major target of the project.

Other project elements include preservation and promotion based on the application of new techniques and experience from other countries in the region and the world.

|

| ADMIRING EYES: Lacquer works on display at a recent exhibition in Hà Nội. VNA/VNS Photo Hiền Anh |

The culture ministry is to provide funding for the Department of Fine Arts, Photography and Exhibition to coordinate with relevant agencies, organisations and localities in implementing the project.

Two traditional lacquerware villages will be targeted for preservation and development: the Hạ Thái lacquer craft village in Hà Nội and the Tương Bình Hiệp lacquer painting village in the southern province of Bình Dương’s Thủ Dầu Một City.

Fine art schools, vocational schools, and training institutions must improve in quality and renew training programmes on lacquerware with a focus on professionalism, according to a decision of the ministry.

Training centres on lacquerware production need to integrate traditional skills with new techniques to foster Vietnamese lacquer artworks and introduce them both in Việt Nam and abroad, the decision states.

Storied history

More than 2,000 years ago, during the time of the Đông Sơn Culture, Vietnamese already knew how to process raw lacquer for use in everyday goods.

Lacquer, the sap coming from some species of trees growing in northern Việt Nam, was used primarily on furniture, boats, weapons, and objects of worship in the past. It later became popular in decorative works at palaces, temples and pagodas.

Increasingly, though, households began to be decorated with pictures coated in lacquer.

Lacquer works have also been found in ancient tombs discovered in Việt Nam’s north. As far back as the Lý Dynasty (11th century) or perhaps even earlier, lacquer was used widely in the ornamentation of palaces, communal halls, temples, pagodas, and shrines.

Dâu Pagoda in Bắc Ninh Province, which was built during the 2nd century, is among a few ancient places of worship to retain Buddha statues from different dynasties painted in gold - proving that lacquerware had been a profession in Việt Nam for some time.

|

| SCENE SET: A lacquer painting by Chu Viết Cường of a landscape in the northern mountainous province of Hà Giang. Photo kenhnghethuat. |

Among the more fascinating examples are lacquer objects discovered in shipwrecks that belonged to the Nguyễn Lords in Việt Nam’s south, which remained intact despite being submerged in saltwater for more than a century.

The department’s research shows that lacquer paintings possess the highest level of artistry in the lacquer craft overall and evolved from traditional handicrafts in certain villages.

“While lacquerware tends to be a main fine art product in other countries, in Việt Nam lacquer paintings are considered unique,” painter Lê Thiết Cương once acknowledged in talking about the value of lacquer painting in the country.

The precise process of lacquerware production was always kept secret and handed down within clans of artisans, who were held in high regard by all.

With increasing sophistication being seen in the craft, the next logical step was to introduce specialisation, either in terms of production steps or the specific application of the lacquer.

In turn, such specialisation led to the foundation of guilds. One may have excelled in processing lacquer while another distinguished itself in gilding or in making vermilion powder.

Guild members lived and worked together, producing lacquerware in wards or along streets named after the craft. Today, in Hà Nội and some neighbouring areas, many streets and villages have preserved their traditional lacquerware production.

Lacquer is found in a range of Vietnamese art, not just in paintings but also in other arts and crafts.

One lacquer product requires artisans complete a set of processes, each with certain skills, in particular dexterity, perseverance and enthusiasm.

Only a few lacquer craft villages are home to highly skilled artisans today, including Hạ Thái in Duyên Thái Commune in Hà Nội’s Thường Tín District, Cát Đằng in Yên Tiến Commune in Nam Định Province’s Ý Yên District, and Tương Bình Hiệp in Bình Dương Province’s Thủ Dầu Một City.

Though Hạ Thái Village was not the first to become involved in lacquer painting, it has long been a centre of the art form in Việt Nam. Started by Vietnamese painters at the Indochina College of Fine Arts in the 1930s, it was introduced to people in the village and many artisans found fame in the craft.

Meanwhile, the lacquer products made in Cát Đằng Village were often hung in ancient tombs and imperial palaces in Hà Nội and the former imperial capital of Huế. Most of these products can now be found along the souvenir streets of Hàng Bông and Hàng Gai in the centre of Hà Nội.

Tương Bình Hiệp, meanwhile, is one of the oldest lacquerware villages in the country, with many products now considered national intangible heritages.

Lacquerware production is now in decline in the village, however, as few younger people wish to follow in the footsteps of their ancestors and preserve the craft, as earning a living from the occupation is anything but easy.

Many cultural preservationists and artists are indeed warning about the decline of lacquer artisans all around the country.

“The traditional lacquer art is in danger of dying out, primarily because there are too few artisans these days,” Cương said.

The painter explained that lacquer painting is quite a complex job and much time and effort is needed from craftsmen while raw materials are expensive.

“There have been fierce debates in the arts community over recent years about the tendency to alter some of the processing stages and use raw materials improperly when making traditional lacquerware,” he said.

Meanwhile, painter Bùi Hoài Mai is concerned about the limited supply of quality materials, mostly those from the lacquer trees growing in the country.

“There are not many areas growing lacquer trees anymore,” Mai lamented.

According to both painters, Thanh Sơn District in Phú Thọ is the only area in the country where good lacquer trees can grow.

“Autumn is the only time to harvest the best lacquer sap,” Cương said. “Many Chinese traders buy the best quality lacquer, with the remainder, of lesser quality, being bought by domestic artisans.”

In order to preserve traditional lacquer art, he said, raw material supplying areas must not only be preserved but expanded, with support provided to lacquer tree growers. VNS