Features

Features

by Nguyễn Khuyến, former Editor-in-Chief of Việt Nam News in his memoir Ship With Paper Sails*

|

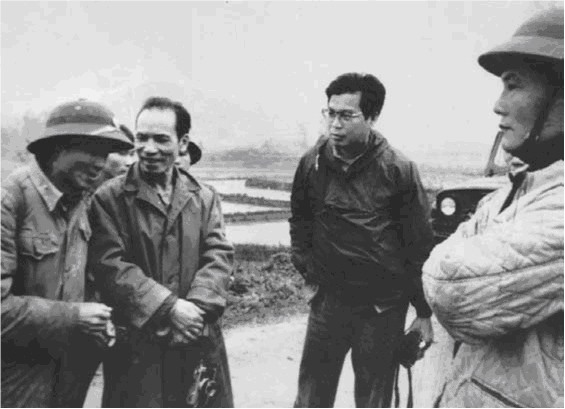

| Ambushed in Lạng Sơn: This picture was taken outside the northern border town of Lạng Sơn on the morning of March 7 1979 by a VNA photographer. We were making a stop to listen to a report on the situation by a local army officer, far left. From right: Me, Japanese correspondent Isao Takano, and Kinh Kha, a guide from the Foreign Ministry. |

by Nguyễn Khuyến, former Editor-in-Chief of Việt Nam News in his memoir Ship With Paper Sails*

... Like most people, I could not foresee that despite the formally signed peace agreements, the war in Việt Nam, then beginning to be "de-Americanised", would drag on for two more years in the south, until the collapse of the RVN [Republic of Việt Nam] government in Sài Gòn in April 1975.

And war continued from 1975 to 1977 in the form of continual cross-border raids conducted by the China-backed Khmer Rouge from Cambodia into Việt Nam’s southwestern regions.

Off and on I travelled to border villages in An Giang Province where Khmer Rouge raiders had sown death and destruction.

War showed its ugly face again in February-March 1979.

Stung by the defeat of its protégé, the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, at the hands of Vietnamese armed forces, China threw 600,000 troops into an invasion of the entire northern section of Việt Nam’s border encompassing six provinces.

On March 7, the day after China had allegedly pulled back its army, I was sent to Lạng Sơn, the most important gateway to China, to cover the aftermath of the brief but particularly violent border war.

I had three companions - Isao Takano, a correspondent of Akahata (Red Banner), the official paper of the Communist Party of Japan; Kinh Kha, an interpretor from the Foreign Ministry; Moro Nakamura from Japan Press Service; and Bùi Thanh, VNA [Vietnam News Agency] chief of staff.

We had no problem in our first hours in the deserted town. On the way out, late in the afternoon, we came under fire. Machine guns from the other end of the road pinned us down on the rubble-strewn road.

Takano was instantly killed by a shot to the head. He was riding in the lead car - one of those Jeep-like Russian military vehicles.

Bùi Thanh and I were in a similar car some fifty metres behind. From the first salvo, a bullet drilled a hole in the radiator. Our driver, Tước, was hit in the hip as he was trying to plug the leak with an oily rag.

Bùi Thanh and I dragged our whimpering driver into a half-destroyed building on the roadside.

Outside, the sustained gunfire was kept up for about half an hour before silence set in.

At nightfall, we heard footsteps and Vietnamese whispering close by. It was an advanced party of the local army.

With the help of our soldiers, we moved Takano’s body and our wounded driver to a deserted pagoda, where we snatched a few hours of fitful sleep before making the journey back to Hà Nội.

My report broke the news of the fatal incident. I jotted it down on the back of a cigarette packet as we were rushing home with Takano’s body. I sent it top priority to the Foreign Desk via the local VNA bureaux then relocated at Đồng Mô, half way between Lạng Sơn and Hà Nội.

That morning of March 8, 1979, I returned to a tearful family. My mother, my wife and my daughters could hardly believe their eyes, seeing me in one piece. When they set about making preparations for International Women’s Day celebrations, I reminded them of a woman somewhere in Japan whose husband had just been killed in action in Việt Nam.

My short report earned me the third prize in a media war coverage competition organised by the Việt Nam Journalists Association in 1979.

That was my first and only direct experience of what turned out to be a long border war between Việt Nam and China.

This war went on for years with increasing intensity. One instance was Vị Xuyên, a major border checkpoint in Hà Giang Province. It was repeatedly attacked by division-sized Chinese forces with the support of artillery and tanks from April -August 1984. The following year, it was the target of about 800,000 Chinese artillery rounds.

In March 1988, two years before Việt Nam and China normalised their relations, the latter blatantly seized several islands, shoals and reefs in the Vietnamese Trường Sa (Spratly) Islands in the East Sea.

I missed most of this long-drawn war because of an extended assignment in Cambodia and various lightning overseas trips. — VNS

*Ship With Paper Sails, Vietnam News Agency Publishing House, 2016