Features

Features

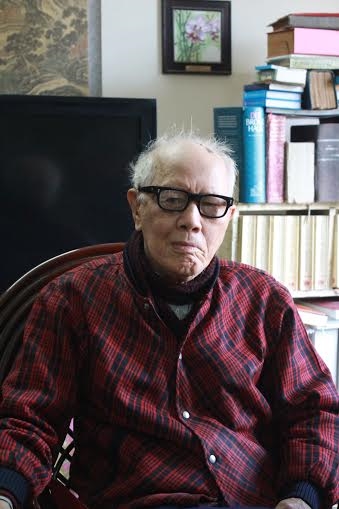

Seen as one of Viet Nam's keenest observers of traditional culture and change, scholar Hữu Ngọc, 98, recently published a tome that teaches visitors what they need to know.

|

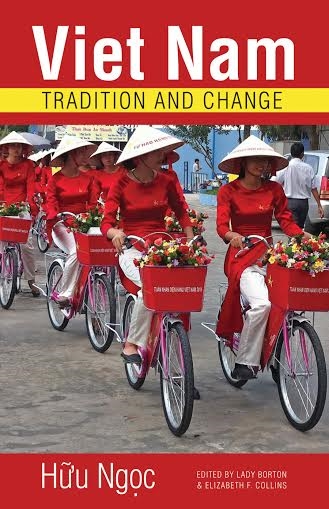

| Bicycling forward: The cover of Hữu Ngọc’s book. |

by Lady Borton

If I were to choose one person to accompany visitors on their first trip to Việt Nam, my choice would be Hữu Ngọc. If I were to choose one book for those about to visit Việt Nam or those unable to visit, my choice would be Hữu Ngọc’s Việt Nam: Tradition and Change.

At age ninety-eight by Western counting (ninety-nine according to Vietnamese), Hữu Ngọc is among Việt Nam’s most famous general scholars. Born with limited eyesight, he reads by holding a text three inches from his near-sighted eye. Yet with his unusual linguistic ability, prodigious memory, and his longevity, he is among Việt Nam’s keenest observers of traditional Vietnamese culture and recent history. For twenty years, Hữu Ngọc wrote a Sunday column in French for Le Courrier du Vietnam (The Việt Nam Mail). An English version appeared as “Traditional Miscellany” in Việt Nam News, the national English-language newspaper. He collected 1,255 pages from these essays into Wandering through Vietnamese Culture, the only English-language book to win Việt Nam’s Gold Book Prize.

Việt Nam: Tradition and Change is a selection from the many treasures in Wandering through Vietnamese Culture.

Hữu Ngọc was born on Hàng Gai (Hemp Market) Street in Hà Nội’s Old Quarter in 1918, when Việt Nam did not yet have its own name on world maps. At that time, the French name for Việt Nam was Annam, which was also the French name for one of Việt Nam’s three regions—Tonkin (Bắc Kỳ, the Northern Region); Annam (Trung Kỳ, the Central Region); and Cochinchina (Nam Kỳ, the Southern Region). The Vietnamese people in all three regions endured colonialism’s rigid and often lethal grasp. The literacy rate among Vietnamese was from 5 to 10 per cent. The schools recognised by the French provided education in Quốc Ngữ (Vietnamese Romanized script) and French to train a small group of Vietnamese students to be administrators at French offices. The curriculum in the country’s few high schools centred on French literature, French history, mathematics, and the sciences, with Vietnamese taught as a foreign language.

During Hữu Ngọc’s student years, Hà Nội had only two state-run high schools—Bưởi School for Vietnamese and Lycée Albert Sarraut for French children as well as for Vietnamese children from the privileged class. Hữu Ngọc was one of two students from Bưởi along with several from Sarraut to place highest in the special examinations. The prize was a ride in the first airplane to circle above Hà Nội.

“This was 1936,” Hữu Ngọc says. “Airplanes were rare in Việt Nam. How extraordinary, how amazing to be up in the sky! Such a wide-open view!”

Việt Nam was still under French rule when Hữu Ngọc completed a year of law school in Hà Nội and taught French in Vinh and Huế, two cities in the Central Region. Việt Nam’s Declaration of Independence placed the Democratic Republic of Việt Nam (DRVN) on the world map on September 2, 1945. Hữu Ngọc joined the Revolution that same year.

However, nationwide independence was short-lived. The French re-invaded Việt Nam’s Southern Region on September 23, 1945, three weeks after the Declaration of Independence, arriving on British ships carrying American materiel. Then, in late 1946, the French re-invaded Việt Nam’s Northern Region and its Central Region, again with American materiel. By this time, Việt Nam was divided into two shifting zones—French-occupied and liberated.

Hữu Ngọc was in the liberated zone. There, he took an examination with forty candidates to choose four who would become English teachers. He placed first. He laughs about this now: “The examiner for the verbal section asked about Wordsworth’s The Daffodils, my favourite poem. I could be unusually fluent, and so I placed first. Wordsworth changed my life!”

He taught English in Yên Mô District, Ninh Bình Province and in the liberated zone of Nam Định Province, where he also served as chair of the Cultural Committee for the Nam Định Province Resistance. While in Nam Định, he created, wrote, and edited a French agitprop (agitation and propaganda) newspaper intended for troops in the French Far-East Expeditionary Corps. Only one known copy of the newspaper remains. Its red banner proclaims L’Etincelle (The Spark). That issue has an article about General Võ Nguyên Giáp, complete with a photograph.

Hữu Ngọc would tie his contraband newspapers to his bicycle’s luggage rack. He remembers passing through a Catholic village. He was biking down a narrow alley when he spotted several French-affiliated African troops, who had arrived for a mopping-up operation. They were on foot and heading toward him.

“Halt!” the soldiers shouted.

“I had to remain calm,” Hữu Ngọc says. “I ducked down an alley. I heard the click of gun triggers engaging. I was sure the soldiers would shoot me in the back. But I was lucky. I had just enough time to turn into another lane and disappear.”

In 1950, the DRVN government called up adult men in the liberated areas to join the army. By then, the French had re-occupied the liberated areas in the Red River Delta. Hữu Ngọc walked hundreds of kilometres out to the Việt Bắc Northern Liberated Zone in the mountains. As an army officer, he supervised the Section for Re-Education of European and African Prisoners of War (POWs). At that time, the DRVN kept the POWs at houses of local Tày and Nùng ethnic-minority people in “prisons without bars”. Hữu Ngọc remembers sitting with three POWs around a hearth in a house-on-stilts. “One POW was French,” he says, “one was an English former officer who’d served in the Royal Air Force, and one was German. We were chatting about anything and everything. I was speaking three foreign languages in the same conversation! I learned a great deal about foreign cultures from the POWs.”

Several thousand Germans had joined the French Foreign Legion, a French mercenary force, after World War II for assignments to Việt Nam. Some deserted to the Việt Minh side.

“I worked closely with Chiến Sĩ (Militant, aka. Erwin Borchers), an anti-Nazi German intellectual,” Hữu Ngọc says. “Chiến Sĩ had joined the French Foreign Legion and then deserted to the Việt Minh before our 1945 Revolution. He handled our agitprop among German POWs. We were close friends. That’s how I learned German.”

The Foreign Legion and the French Far-East Expeditionary Corps in Việt Nam had nearly twenty different nationalities. Many POWs had come from the French colonies in northern and Central Africa. Hữu Ngọc and his colleagues organised lectures and printed training materials on nationalism to persuade POWs (particularly those from other French colonies) that they had been assisting the French in an unjust war.

Then the Vietnamese periodically released their “best students” back to the French side to organize within French ranks. The French soon caught onto the scheme and sent the newly released POWs back home. Once they were back home, many of these liberated African POWs began to organize for their own national revolutions. Perhaps it is no accident that some Algerians identify the beginning of their revolution as May 8, 1954, the day after the Vietnamese victory over the French at the famous Battle of Điện Biên Phủ.

Hữu Ngọc received a People’s Army Feat-of-Arms Order for his agitprop work. His assignments during the French War had taken him between POW camps-without-bars to staff headquarters and to other sites in liberated Việt Bắc. Like many other army officers, he hiked along mountain paths. One day, at an intersection between two trails, he met one of his former Nam Định students, a lovely young woman, who by then was an army nurse and who, before long, would become a pediatrician. The two courted in the mountains and married in a simple wedding with tea, cigarettes, and their friends’ congratulations. They shared three days off in the special honeymoon hut Hữu Ngọc’s colleagues had built. Then he and his wife returned to their assignments, seeing each other whenever possible. Their first child was born in the mountains.

After Hà Nội was liberated in October 1954, Hữu Ngọc and his family moved back to the capital. These days, he and his wife live with one of their sons and his family. Without fail, their children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren gather each Sunday for lunch, rotating from one household to another. Over the years, foreigners from many countries have joined Hữu Ngọc’s family for Sunday lunch, formerly sitting in a circle on a reed floor mat but now sitting around a large, polished table, yet always conversing in many languages.

During the American War (the term Vietnamese use for what Americans call “the Vietnam War”), Hữu Ngọc was deputy director of Việt Nam’s Foreign Languages Publishing House. He and Nguyễn Khắc Viện, the publishing house director, edited and translated Vietnamese poetry and prose for their thousand-page Literature Vietnamienne (Vietnamese Literature, 1979). Publication of this work was a major cultural event. Le Monde (The World), the leading newspaper in France, noted: “Every day, a hundred American B-52s pummeled North Việt Nam. Nevertheless, the Vietnamese did the work to publish this major anthology of their literature in French.”

The Foreign Languages Publishing House (also known as Red River Press) printed books in Arabic, Chinese, English, French, German, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, and other languages, including Esperanto (a constructed international language).

“The Esperanto period was so interesting!” Hữu Ngọc says. “Not many people knew Esperanto, but those who did were fanatical. They would translate from Esperanto into their own languages. Esperanto multiplied our efforts at the publishing house because Esperanto translators worked in both the communist and the capitalist blocs.”

Hữu Ngọc was director of the publishing house from 1980 until his retirement in 1989. When Việt Nam began to open, he changed the name to Thế Giới (World) Publishers because all countries in the communist/socialist bloc had a Foreign Languages Press. Hữu Ngọc wanted to signal that Việt Nam was not only unique but also open to the whole world, including the West.

During the American War, the publishing house had paid particular attention to English. Those books and Vietnamese Studies—a quarterly founded by Nguyễn Khắc Viện in 1964 and still published today—reached American activists and scholars.

Between the end of the American War in April 1975 and September 1989, Việt Nam faced war on two fronts: the Khmer Rouge incursions into southern Việt Nam with the subsequent war in Cambodia and the Chinese invasion into six Vietnamese border provinces. The then US government politically backed the genocidal Khmer Rouge and the Chinese invasion. Thus, although many say the American War ended in 1975, in truth, re-unified Việt Nam first enjoyed peace only in 1990.

The United States responded to the war in Cambodia by enforcing an even stricter embargo, which entangled all Western countries except Sweden. The embargo kept out not only Western goods and spare parts for any machine produced or patented in the West but also books, including medical journals. Việt Nam’s leadership had already instituted a rigorous, intensely collectivised socio-economic system, which stymied individual incentives in agriculture, trade, business, education, and scholarship. Although Việt Nam received military aid from the former Soviet Union, with the exception of Sweden, the country essentially had no outside assistance for food, medicines, and post-war reconstruction. Everything was rationed. Everyone was gaunt. Typhoons, floods, and droughts compounded the stress. Nevertheless, by the mid-late 1980s, Hữu Ngọc was already looking ahead to normalised relations between Việt Nam and the United States. He had published works about French, Japanese, Lao and Swedish culture. Now, he wanted to write about American culture.

Hữu Ngọc often cites this caution: “You can go to Paris for three weeks and write a book, but if you live there thirty years, you dare not write a word.”

With his own caveat in mind and long before the Internet, Hữu Ngọc read everything he could about American culture. He asked any Americans he met to send books with the next visitor and to write articles. He went on to create a thousand-page volume in Vietnamese with essays from friends, summaries from his own research, and a very extensive bibliography. Hồ Sơ Văn Hóa Mỹ (A File on American Culture) remains in print today after twenty years. Hữu Ngọc’s oeuvre also includes many books about Vietnamese culture. Perhaps most important among them is his Dictionary of Traditional Vietnamese Culture, which has been available in Vietnamese since 1994 but was published in English only in 2012. This must-have book holds gems on every page.

When Hữu Ngọc was still in his late eighties, he walked to work, carrying his bag of books and covering the five kilometres in a little more than an hour. He used his far-sighted eye to negotiate Hà Nội’s famously horrendous traffic while reciting poetry in Chinese, English, French, German, and Vietnamese, with William Wordsworth still among his favourite poets. And so, it is no accident that Hữu Ngọc’s Wandering through Vietnamese Culture opens with his favorite lines from Wordsworth’s The Daffodils.

Several years ago, Hữu Ngọc’s family moved too far from World Publishers for him to walk to work. Now, for exercise, he walks forty-five minutes every day, covering three kilometres inside his house, often reciting the ten Buddhist precepts. He begins with the first precept, then recites the first and second precepts, then the first and second and third. When he finishes all ten precepts, he starts over again. Then Hữu Ngọc continues his day, writing his essays in heavy black ink, a felt-tip marker as his pen.

Hữu Ngọc has a rather wry approach to his prolific writing.

“Do you know why I write?” he will say, pointing to the shelves of books he has written and edited. “When I need to check something, I know where to look!”

Three days a week, Hữu Ngọc rides on the back of his son’s motorbike to his office at World Publishers. He is a mentor to many. His door is open. Whoever pops in is welcomed, introduced, and linked to anyone already in the room. His open door emphasizes the great role of “the random” in life. Hữu Ngọc says his own life has been a continuous series of random events. As a youth in Hà Nội, he dreamed of marrying a girl from the mountains and nesting in a house by a stream. However, the random from an interview question and lines from his favourite Wordsworth poem led him to teaching. In 1945, he joined the Việt Minh because of random events of history. His limited eyesight and assignment to work with POWs and the random in life led him to a career as a researcher in culture. Yet, despite his belief in “the random”, Hữu Ngọc recognises opportunity without being an opportunist. Those who take advantage of his open door know that he has an unusual ability to discern and develop a new idea or a novel approach.

After retiring as chairman of the Vietnam-Sweden Cultural Fund and of the Vietnam-Denmark Cultural Fund, in 2012 Hữu Ngọc established the Cultural Charity Fund to provide children in remote areas with world literature. The translated books range from works by American John Steinbeck to Russian Boris Pasternak to the newest Harry Potter books. He has also given rural children the chance to study English first hand by organizing courses taught by English-speaking volunteers.

Hữu Ngọc continues to give his ever-changing lecture, “Three Thousand Years of Vietnamese History in One Hour". He will hand Wandering through Vietnamese Culture to a listener in the first row. “Take a look,” he says. “Pass it around.” One by one, members of his audience marvel at the book’s weight and peruse its 1,255 pages, pausing here and there to measure the book’s depth.

For this volume, Professor Elizabeth Collins from Ohio University has worked with Hữu Ngọc to select essays from Wandering through Vietnamese Culture. This was a huge task, one I had seen as important for years but had found overwhelming. Hữu Ngọc worked over successive drafts of the Contents, restructuring some sections, making minor changes in other sections, and adding a few pieces, which do not appear in Wandering through Vietnamese Culture.

A weekly newspaper column is like a ticking metronome rushing the writer on and leaving little time to ponder chords, trills, and grace notes. However, collecting columns into a book of essays gives the writer a chance to revisit his work—to consolidate some pieces, expand and tighten others, and to play with the melodies and harmonies of language. At ninety-eight, Hữu Ngọc is still writing weekly essays and assembling books. He is busy moving forward. For that reason, he asked me to assume responsibility for shifting his selected newspaper columns into the essays that appear in this volume.

That task provided me an opportunity for many random discussions of this text in Hữu Ngọc’s office. In consultation with the author, I have updated paragraphs, made corrections, and inserted some sentences and phrases for clarity and context. I have left in repetitive details because readers may approach the essays out of order. I have also added a note on the Vietnamese language, a historical timeline, and an index.

Vietnamese Literature, the English version of the French anthology, was the source for many of the excerpts from poetry and prose that Hữu Ngọc quoted in his newspaper columns. The Vietnamese works in Vietnamese Literature had been translated sometimes from Chinese (Hán) or Vietnamese (Nôm) ideographic script into Romanized Vietnamese script (Quốc Ngữ), then into French, and, only then, into English. As a result, understandably, many English translations in Vietnamese Literature and in Hữu Ngọc’s original newspaper columns were rather distant from the original texts.

For this reason, I have re-translated all the quotations from Vietnamese works, returning to the original Romanized Vietnamese versions and, when relevant, to the transliterated Hán and Nôm versions of the ancient poems and prose. By adding the Romanized Vietnamese titles, I hope to encourage interested readers to explore the original texts, many of which are available on the Web at www.thivien.net in Quốc Ngữ and, for the ancient works, also in Hán or Nôm at that same website. Some of our translations in this volume appear in our other books and articles and will appear in the new edition of Vietnamese Literature.

Hữu Ngọc chose not to read the final manuscript for this book because he wants to conserve his time to work on new projects. His son, Hữu Tiến, read the manuscript and alerted me to several errors. Phạm Trần Long, deputy director of World Publishers and the book’s editor in Việt Nam, is always a careful, helpful reader. Trần Đoàn Lâm, the director of World Publishers, is well versed in Chinese Hán script and Vietnamese Nôm ideographic script. In addition, he is fluent in Russian and English and can read French. Mr. Lâm has checked our translations with the original texts (Hán, Nôm, Quốc Ngữ, and French). As director of World Publishers, he is also the book’s final Vietnamese reader. Trần Đoàn Lâm brings to any text an extraordinary ability to think broadly yet concentrate on the smallest detail.

This book does not attempt to be a systematic study of Vietnamese culture or of Việt Nam’s traditions and changes. Rather, it is a compilation of some of the essays from Wandering through Vietnamese Culture that reflect that theme. As a result, there may be important events, people, and issues not covered in this collection.

Now, with many of us working together and with assistance from many other colleagues in Việt Nam at World Publishers and in the United States at Ohio University Press, we have Việt Nam: Tradition and Change, an accessible and absorbing tour of Việt Nam’s history and culture with scholar-writer Hữu Ngọc as our guide. VNS

|

| Stories to tell: Scholar and writer Hữu Ngọc. Photo Van Anh |