Society

Society

An excerpt from The Bridge Generation of Vietnam by Nancy K. Napier and Dau Thuy Ha

|

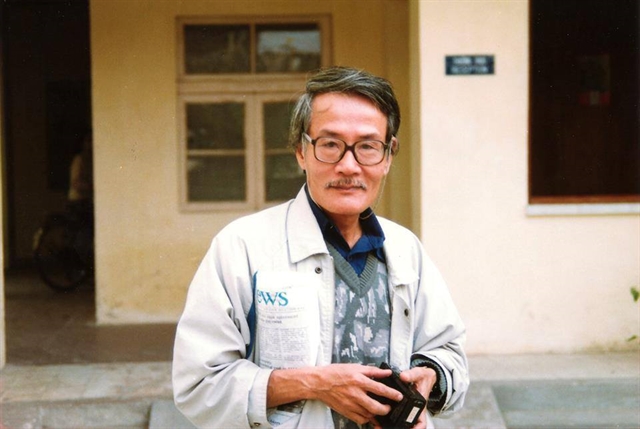

Nguyen Cong Khuyen - The Journalist

(An excerpt from The Bridge Generation of Vietnam by Nancy K. Napier and Dau Thuy Ha)

“My bicycle was a great asset. It meant life. ”

Nguyễn Công Khuyến

Newspaper legend Nguyễn Công Khuyến (pronounced “coo yen”), in his eighties, has suffered from Parkinson’s disease for twenty years, so his movements are slow and deliberate. He bends ninety degrees at his waist, turning his head to the side to see me. While his posture is bent, his mind is sharp, and he still can slip into journalist mode, painting vivid pictures that made me feel I was with him during the hardships of the American War. We also sat in long stretches of silence. Working in Asia for so long, I’ve become comfortable with silence—fifteen to twenty, or even thirty, seconds passed while we sat still, together. Eventually, Khuyến spoke, offering another good story. But during the silence, he stared at and into me.

Khuyến’s name is difficult for many foreigners to pronounce so when he began working with them, he gained the nickname “Mr. K.” A longtime journalist with the Vietnam News Agency, Khuyến founded Vietnam’s first government-funded English language newspaper in 1991. Hà (co-author of this book) worked at the Foreign Languages Publishing House in 1991, now called The Gioi Publishers, which in Vietnamese, means “the world.” She recalls the excitement around the office when she heard about the “new kid on the block.” How could it be possible in Việt Nam, she wondered, to turn out a daily newspaper in English with such scarce resources? But, Mr. K and his colleagues did pull it off and the “new kid on the block” remains today.

In fact, in the early 1990s, when I worked in Việt Nam, The Việt Nam News was my local source of information, as well as a gauge of the government’s attitude toward foreign ideas at any given time. Some months, western movies and music were out of favor as a “campaign against social evils” took hold. Other times, ideas from the West flourished, and music like Mambo Number 5 blared on my neighbors’ tape players a few weeks after the song hit the charts in Germany, in the mid-1990s.

* * *

Nguyễn Công Khuyến - The Journalist

By 2017, Khuyến lived near Khâm Thiên Street, which looms large in older Hanoians’ memories, because so many lost relatives and friends during the December 1972 bombings of the area. It is the street that thirteen-year-old Hằng walked down, seeing dead people and white headbands. Today, the east-west street is modern and energetic, jammed with cars and motorbikes, shops and bustling restaurants. But at 47 Khâm Thiên Street, on the south side, is a memorial to those who perished during the ten days of bombing. Tucked into a narrow space between two towering buildings, the plate at the top of an obelisk reads “Khâm Thiên residents nurture deep hatred of the U.S. enemy” (“Khâm Thiên khắc sâu căm thù giặc Mỹ”). I’m always a bit taken aback by such phrases or messages, written or spoken in a frankness that is very Vietnamese. In front of the obelisk stands a statue of a young mother, named Mrs. De, carrying her lifeless one-year-old child. The mother and child died at the location where the statue rests, under rubble from the bombs on the night of December 26, 1972. The child drapes over the mother’s outstretched arms—head falling back, legs dangling. The pose reminded me of the way soldiers carry flags during Vietnamese state funerals: a long red flag drapes over the outstretched arms of a soldier who follows the casket of the statesman being laid to rest.

|

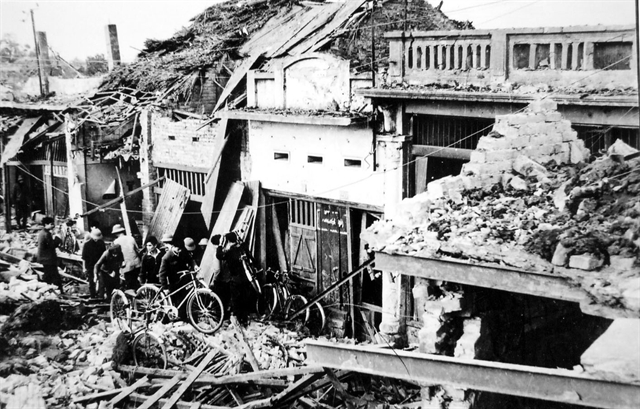

| US B52 'Flying Fortress' planes carpet-bombed Hà Nội on December 26, 1972. They destroyed a section of the city 50-70m and 1km on what was Khâm Thiên Street, killing 287 people and injuring 290 others. The bombing raid destroyed nearly 2000 houses, schools, pagodas and healthcare clinics. Overcoming the wounds of war, people of Khâm Thiên have rebuilt their houses, schools, pagodas and clinics, bringing them back to normal life. There is a memorial statue on the street and these days, surviving family members lay flowers and light incense so that those who died can rest in peace. VNA Archive photo |

Khâm Thiên Street may be best known for the twelve days of horrific bombing in December, but the story began earlier. In May 1972, President Richard Nixon initiated “Operation Linebacker,” an aggressive bombing of the north. The goal was to bring North Vietnamese leaders to the bargaining table, which did happen when the Americans and Vietnamese met in Paris in August to negotiate. By the end of October, the two sides had reached an agreement that prompted Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s famous statement that “peace is at hand.” Peace was nowhere near at hand, though. The United States had not cleared the deal with the South Vietnamese president Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, who refused to accept it. In December, the United States accused the North Vietnamese of “stalling,” and on December 14, issued a seventy-two hour deadline to restart negotiations. The Vietnamese refused to return to the table.

Nixon then approved “Operation Linebacker II,” bombings to run from December 18-30,1972, using a dramatically different approach. During much of the war, the Americans had used fighter jets, carrying smaller bombs, and focused on fuel depots and munition warehouses. The new endeavor used B52 planes: larger, slower but able to carry bigger and more lethal bombs. The planes flew lower to the ground, so “carpet bombing” was more destructive. Yet, because they flew lower, the Vietnamese could shoot the planes down, and they did.1

The operation targeted airfields, railroads, warehouses, and power plants in and near Hà Nội and Hải Phòng, a major port city along Vietnam’s northern coast. By the end of the twelve days, the Americans had flown nearly 800 night sorties, dropping 20,000 tons of bombs, but many hit unintended sites. One of the most memorable happened on December 22, when bombs eliminated a major wing of Bạch Mai Hospital, the country’s top medical school and training hospital, killing twenty-eight staff and patients. The loss of innocent life appalled the Vietnamese leaders and people. Instead of “coming to their knees,” the Vietnamese dug in.

|

| Starting on December 18, the US launched Operation Linebacker II, employing the Seventh Air Force and Navy Task Force 77 for an aerial bombing campaign to destroy major targets in Hà Nội and Hải Phòng, in what the US termed as "maximum effort" bombing raids carried by B52 bombers. It was the heaviest US bomber strikes since WWII, in an attempt to send Việt Nam back to "The Stone Age," as US Air Force General Curtis LeMay wrote in his 1968 memoir, with the intention of "taking out factories, harbours and bridges until they have destroyed every work of man in North Việt Nam."The bombing raid ended in what Vietnamese termed as 'Điện Biên Phủ In The Air', with enormous Vietnamese fatalities, Long Biên bridge broken and devastation on Khầm Thiên Street, Bạch Mai Hospital, Hà Nội's University of Foreign Languages Library and many more. The Geneva Peace Agreement in January 1973 came as a result of this particularly fierce chapter in the American War. VNA/VNS Photo Văn Bảo |

On December 24, bombers hit the railroad station again. After a day of respite—Christmas Day—the bombing renewed. On December 26, at 10:30 p.m., the bombers demolished Khâm Thiên Street. One official report claimed that over 5,000 families, or 28,000 people, lived in the Khâm Thiên area,2 and that 2,000 to 2,380 civilians died that night. For days afterward, people carried the dead in wooden coffins through the neighborhood. Many more wore white headbands, the symbol of death, and spent the day wailing, trying to bring back a dead relative.3

The American singer and anti-war activist Joan Baez happened to be in Hà Nội during those twelve days. She arrived in Hà Nội on December 16 and planned to leave on December 23, after meeting with and delivering letters to American POWs. But when the worst bombing in Hà Nội’s history started on December 18, all planes were grounded, and Baez was unable to leave until December 30.

Rolling Stone's Tim Cahill wrote about Baez’s time in Hà Nội, drawing upon her journal and interviews with her.4 She told of one woman weeping uncontrollably, her face swollen, sitting on rubble. Another woman called out for her dead sons buried under rubble from a collapsed house. One whole family died, while embracing each other, trapped under the wreckage strewn along Khâm Thiên Street.

Baez came away with gut wrenching images. She told Cahill about one photo of a young Vietnamese girl, perhaps seventeen years old, sitting on a high stool. Her legs hung down, but she had no feet since her legs ended at mid-calf. Here’s Baez:

“She told me that she lost her legs a week before her wedding. She didn’t think her husband would want her, but he carried her to the wedding on his back.”

One of the best Vietnamese movies about the period is called “Hà Nội 12 Days and Nights.”5 It follows the lives of several characters in Hà Nội, in and outside of the city. In the film, we hear a voice from loudspeakers calling for people to run for shelter, the whistles warning of incoming planes, the streaking sound of bombs falling and bursts of red in the sky. Some nights brought four or five raids. A few nights brought ten or twelve, and people remained in the shelters all night.

|

| Over the course of 12 days and nights, 2,380 people died and 1,355 others were wounded in a carpet bombing campaign that saw 40,000 tonnes of bombs dropped on Hà Nội, Hải Phòng port city and Thái Nguyên Province. More than 40 years later, vegetation and housing complexes cover the old bomb craters. The bravery of those who lived and died during Operation Linebacker II has not been forgotten by generations of Vietnamese since. VNA/VNS Photo Văn Bảo |

In one of the movie’s final scenes, Hanoians come to the side of Hữu Tiệp lake in Ngọc Hà village, where the final plane of the onslaught has crashed. The crowd cheers that the plane has landed in the water, broken into warped pieces of metal, and that the fighting is over. One man laughs hard, but then pounds his foot on the wreckage, kicking it and screaming in anger. Next, he picks up a small boy, holds him above the ruins of the plane, and says, “Piss on it, kid,” which the child does. The crowd cheers and laughs again at the humiliation given the plane, the downed pilot, and the country that tried to “bring Hà Nội to its knees” and failed. Finally, an old man, who has lost friends and his beloved only daughter, shuffles forward, his face in anguish, and places burning incense sticks onto the plane. He turns and walks away, and the crowd realizes that no one wins when someone dies, no matter what side.

Accurate or at least consistent information about what happened in those twelve days is hard to come by. The estimates of deaths, injuries, houses destroyed, and B52s shot down vary widely. The Americans claimed that sixteen B- 52s were destroyed, and nine were damaged. In the “Hà Nội 12 Days and Nights” movie, the number of downed B-52s is thirty-four, with a total of eighty-one American airplanes brought to the ground. It matters on one level, and yet on another, as anyone who lived through it might say, even one death or injured martyr, Vietnamese or not, is too many.

* * *

Today, the Khâm Thiên neighborhood seems upscale, filled with leafy trees and quiet streets. Khuyến lives in a walled off cluster of four-story row houses, each a single room wide. Huge vines and bougainvillea gardens enclose the houses, making the street green year round. All of the houses hide behind walls of iron, and some have spikes at the top of the walls to keep thieves and burglars out. Khuyến’s metal front gate, in Peter Pan green, stands at least seven feet high and sports a small square opening at eye level so family members can see who has come to visit. When I went the first time, his daughter opened the door and apologized for her English, saying she was visiting from Germany. I switched to German, and we got along fine. Her teenage son (Khuyến’s grandson) Andre, speaks German, Vietnamese, and English equally well, and joined us for the interview with his grandfather. Andre and I continue to correspond as he tells me about his medical school training and his thoughts on German and American politics.

I followed Khuyến’s daughter up a steep flight of cement stairs going from ground level to the second floor of their house, into the living room, which is about one hundred square feet. Bookshelves line two walls, holding volumes such as Le Carré spy novels, photo books, and novels, many with English titles. They range from books by authors like Tim Winton from Australia to Americans like John Updike and David Baldacci. A Vietnamese translation of Gillian Flynn’s book Gone Girl rests alongside. Khuyến confesses that his ability in the language began before the coronation of England’s Queen Elizabeth II. His skill improved thanks in part to a steady supply of books from a friend who worked at the national library in Hà Nội who smuggled books out for him to read. Books unavailable to the public became his passion, especially westerns and spy stories, which kept his reading passion alive even in the thick of the American air war.

|

Photos on the wall show Khuyến as a young news reporter, as a husband with his wife and toddler-aged daughters, and as a journalist meeting famous people. This comfortable home contrasts starkly with where he and his family lived for twenty-five years: a one room, 200-square- foot space that held two double beds and a small desk. As he describes in his book, Ship with Paper Sails, they lived in one of thirteen apartment buildings built with aid from North Korea in the 1960s.6

To learn that North Korea offered aid money to Vietnam surprised me. In fact, the two countries established diplomatic relations in 1950 and were very close for nearly twenty years. During the American War, North Korea was a strong supporter of North Việt Nam, offering military equipment and training, pilots and uniforms, economic aid, and education for university students. North Korea remained a close ally of North Việt Nam’s until 1968. But once the United States and North Việt Nam broached the topic of peace talks, North Korean support for Việt Nam waned. The North Koreans feared that with peace, the U.S. would be less distracted and might shift its focus back to the Korean peninsula. The two countries must have made up some time ago, since North Korean soldiers periodically show up in Hà Nội for meetings, and in 2019, Hà Nội gained the spotlight for a North Korea-US summit.

During the American War, Khuyến’s work as a deskbound copy editor for the Vietnam News Agency was, by his reckoning, tedious. But in 1964, the news agency sent him to the field. One of the most difficult assignments was when he learned that nearly all of the family of his wife’s elder uncle had died. Khuyến, the journalist, went to cover the tragedy. Nine people perished: father, mother, and seven children. All had been refugees freshly repatriated from Thailand where they had sought shelter during the First Indochina War (1946-1954). Hardly had they settled down in Hà Nội in 1964 when disaster struck.

“They were sleeping peacefully and then a bomb hit. Senseless killing. I had to write about it, as a journalist, without indulging in self-pity.”

* * *

During the war, Khuyến’s ability to move around the city, and eventually into the countryside, was dependent on his bicycle.

“My bicycle was a great asset. It meant life. ”

When he said that, Khuyến’s grandson leaned over to me.

“He has said that many times. A bicycle was his ‘greatest asset.’ ” I got the impression that he found such a statement hard to fathom, coming from life in Germany or even in Hà Nội where autos now dominate.

But it was a statement I did hear from many Vietnamese who lived through conflicts and the subsidy period after the American War. Parents taught children how to ride and repair bicycles at the same time. Everyone who rode carried at least a tire pump and patches to fix the tires or inner tubes. By the early 1990s, though, bicycle repairmen squatted on street corners throughout Hà Nội with tools, tires, and tubes. They also had plastic containers of petrol for motorbikes. By the 2000s, fewer people could repair those same bikes and motorbikes.

But the “great asset” was not always reliable, since it had a tough life too. Even Khuyến’s commute in the city, which was less than a mile, could be a challenge, sometimes taking two hours. When the bike broke down, he pushed it onto the sidewalk and tried to fix it.

‘The inner tube was full of patches. Sometimes I replaced the inner tube with two outer tubes doubled up. There was no guarantee it would not explode. If the chain broke, I had to put it together again link by link. When it was worn out, I turned it upside down. And the free wheel-—what makes it move free inside—is a spring. When it broke, I used a piece of hard rubber to fix it. The noise it made—instead of tick-tick-tick—waspuu-puu-puu. Things like that, fixing the bike or pushing it if I could not, became normal. We took that for granted as a fact of life. We gave our thoughts to the war, how it was going, how soon we could conclude it, and could we stay alive until then. ”

His asset also meant the chance to visit his family when they had evacuated the city. Sometimes the government sent his family far from Hà Nội to safer ground, and other times they went to nearer locations. If they were nearby, Khuyến visited every weekend. He mounted his Chinese- made Phoenix bicycle on Friday at midnight for the twelve- mile journey. He piled rice, cooking oil, sugar, and more onto the bike, making it heavy and wobbly as he traversed dirt roads and fields of maize. He remembers that he and hundreds of others pedaled down the dark roads without speaking, all going on similar missions, their routes lit only by the moon and stars. The noise of the night came from frogs in creeks and lakes and the crunch of tires or rubber sandals on the gravel and dirt roads.

If he was lucky, Khuyến arrived Saturday morning by five a.m., before his children woke up. They shared lunch and caught up on their lives. Then, not having a watch, Khuyến relied on the sun for the signal to begin cycling back to town to be in the office for the night shift.

* * *

For Khuyến and many others, separation from family was the worst part of war. From 1965 onward, any person considered “nonessential” to the immediate war effort retreated to the countryside for safety—older citizens, children, and women with jobs that were less critical. Often families split up, and sometimes parents separated the children as well in the hopes that if some died in a bombing, others might live if they were in a different location. Everyone I spoke with remembered the misery of being apart. Yet, they accepted it, and as many commented, “We had no choice.”

Having no choice can lead to resignation, giving in even if not giving up. But the people I spoke to survived, living through death, separation, or near starvation. Instead of resignation, their stories showed resilience. I wondered how they managed to find that strength.

I found one answer from some recent research on Vietnamese who went through Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Many Vietnamese who lived in New Orleans during the disaster moved elsewhere in Louisiana or Texas after the hurricane. They fared better than other ethnic groups and were more likely to rebuild their homes and communities.7 But why? The researchers found that culture and history made the difference. Most of the Vietnamese had come to the United States after the American War as refugees. They drew on their common experiences from the war and from being refugees and, because they knew other Vietnamese who had the same past hardships, they could—as a group—focus on how to “come back” rather than on giving up.

* * *

Khuyến admits that during the days of evacuation, bombs, and enduring separation, he knew that life was not predictable or certain. He took solace in poetry. When he was on his way to visit his family in the countryside or during the ride back to the city the next day, Khuyến often mumbled to himself the last lines of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Mariposa”:

“Suffer me to take your hand.

Suffer me to cherish you

Till the dawn is in the sky.

Whether I be false or true,

Death comes in a day or two. ”

Khuyến said he was not being pessimistic but rather he was just trying to be rational, to be prepared.