Op-Ed

Op-Ed

|

Anh Đức

I remember vividly my childhood journeys on the backseat of my parents' bicycles, surrounded by dozens of bicycles riding together in the busy streets of Hà Nội.

Motorcycles cost a fortune back then, and it was not until 2000 that we got our first motorbike, a Chinese-manufactured bike in the form of the Honda Dream, or as the Vietnamese would call them, 'Dream Tàu'. Cars were even rarer and were perceived as a symbol of wealth; you could only see one or two parked in the streets during the 90s.

|

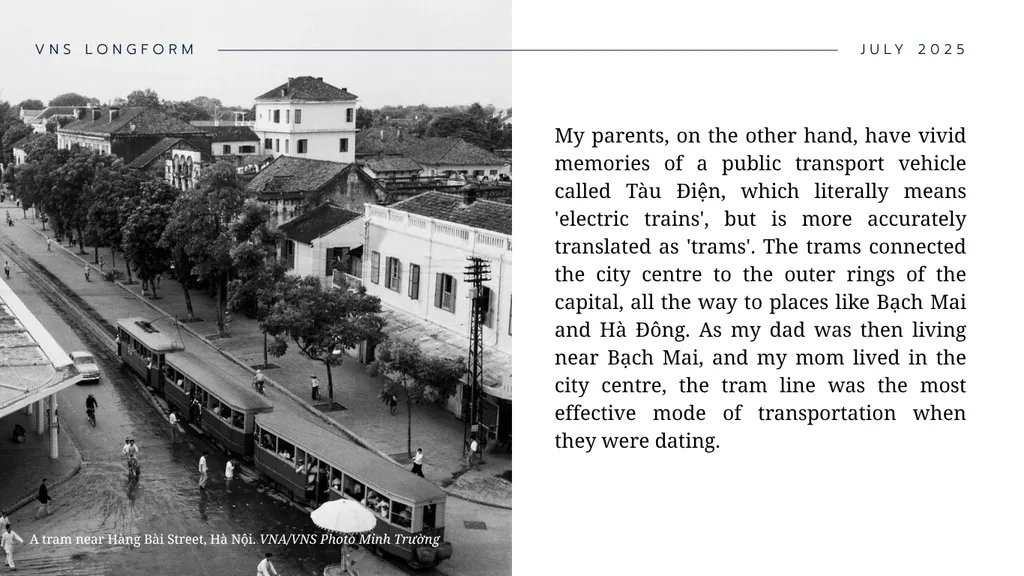

And then all of that rapidly changed as Việt Nam developed. As the economy progressed, trams were discontinued and replaced by buses. Motorcycles started popping up like crazy. By the time I was in high school, even some of my peers had their own mopeds. And with entry-level affordable cars available by 1998, owning an automobile was no longer a wild dream for most Vietnamese families.

But there is one more memory from my childhood that many others brought up in the Hà Nội of the 90s will also recall: the blue skies on summer days. As we progressed into the 2010s and the 2020s, these days became rarer, and grey and white became more dominant.

After a mild pneumonia sent me into the hospital last June, my doctors recommended that I took up a light sport for lung recovery. I eventually chose cycling.

|

My most common cycling route is described by many as 'bizarre': I tend to travel in rush hour from the office in the city centre down Nguyễn Trãi Road all the way to the outskirts of the city and then back again to the Old Quarter.

But through that route I was able to see the reality of air pollution and traffic congestion in Hà Nội. A chaotic traffic game of fill-in-the-blanks. The smell of gasoline and sometimes a dash of black fumes from buses. All this as residents rush to get home as soon as possible — and it gets even worse on rainy days. A summer sunset on my cycling route is few and far between, but a sight to behold.

|

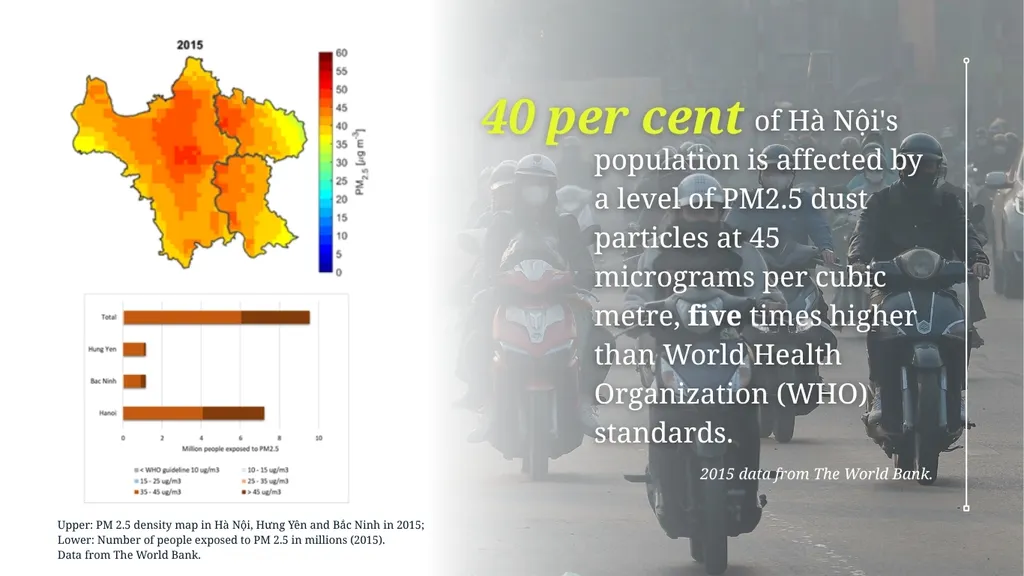

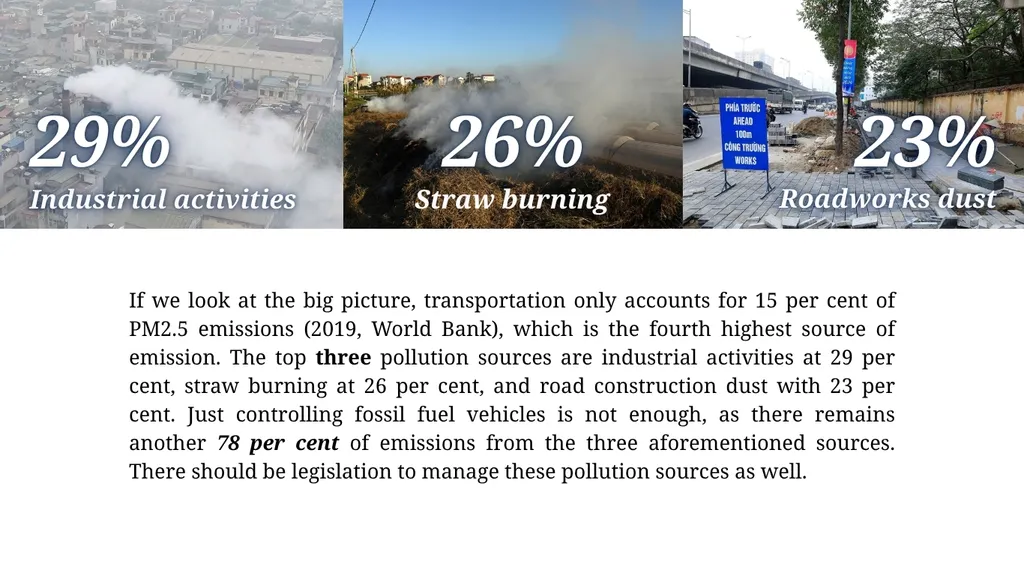

A study by the World Bank in 2020 suggested that 40 per cent of Hà Nội's population is affected by a level of PM2.5 dust particles at 45 micrograms per cubic metre, five times higher than World Health Organization (WHO) standards. Fourteen per cent of suspended particulate matter emissions come from traffic, according to a five-year estimate from 2015-2020 by the Hà Nội Environment Department.

The World Bank cited a study from the Development Policy Centre at the Australian National University that found ambient air pollution causes more than 52,000 deaths every year nationwide. Common respiratory and cardiovascular conditions caused by the rise of traffic-related smog include stroke, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, lung cancer, Acute Lower Respiratory Infections and others.

|

According to the World Bank, the medical and social costs of dust particle-related illnesses are huge: about 7.74 per cent of Hà Nội's GRDP (in 2020). A reduction of PM2.5 levels to match WHO's recommendations would save the Government up to VNĐ114 trillion (US$4.3 billion), about 5.1 per cent of the nation's GDP. An estimated 4,500-13,300 lives would also be saved annually.

Việt Nam is also aiming to achieve its COP26 commitment of net-zero emissions by 2050. Cleaner urban transport is a crucial element to achieve that goal.

|

The Government on Sunday set out a stepping stone on that journey by announcing a ban on fossil fuel vehicles inside Hà Nội's Ring Road 1, which encompasses the city centre and main wards, from July 2026, with a view of expanding the ban to areas inside Ring Road 3 in 2028.

Setting a timeline to swiftly ban the capital's fossil fuel vehicles starting next year is a bold ambition. For perspective, Paris plans to ban petrol and diesel cars by 2030, a goal the city announced in 2017. Not to mention, Paris' public transportation system is more well developed than Hà Nội's.

Hà Nội can go green, and the switch from diesel to electric will happen sooner or later. But it is not a matter of flipping the switch from one to zero; it needs a plan and a roadmap to support the capital's residents, who will experience difficulties with their current diesel motorbikes and cars, and may have to quickly sell their vehicles and buy new ones.

In terms of public transport, the system should be developed quickly, and there should be a change in the locals' attitudes, as they always prefer personal transport methods rather than public transport.

|

The clock is ticking, and there is one year left until the deadline. If the switch is complete, this would change the capital in ways never seen before.

And I will be on my bike waiting for the blue skies and the bicycles on the streets to return soon. VNS

|