Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

Thu Vân talks about several instances of babies being switched by mistake at birth, and the pain, suffering and trauma that follow for parents and children with the realisation that they’ve been bringing up the “wrong” child and have been brought up by the “wrong” parents for years.

|

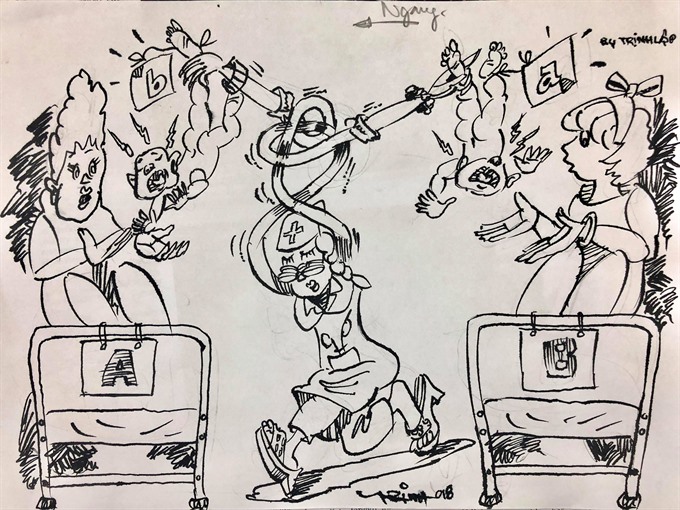

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

by Thu Vân

It’s like a plot that only the most twisted, sadistic minds can think up, so the casual way in which it happens and the even more casual way in which redemption is found are as shocking as the plot itself.

Does this sound confusing, convoluted and tortuous?

If it does, that’s exactly how I feel, and you can add a liberal dose of anguish, anger and frustration.

I am talking about several instances of babies being switched by mistake at birth, and the pain, suffering and trauma that follow for parents and children with the realisation that they’ve been bringing up the “wrong” child and have been brought up by the “wrong” parents for years.

And then, everyone involved on the side of the authorities, officials and hospitals, redeem themselves by saying sorry and “correcting” the mistake by holding a ceremony to hand over the “right” children to the “right” parents. They smile, shake hands, throw in some compensation money.

Case closed.

Except, it’s not (expletive) closed.

Two baby girls, born on January 13, 2013, in Bình Phước Province, within 15 minutes of each other, were mistakenly switched at the hospital. Three years later, the truth shocked the public and broke many hearts.

Early this month, a similar tragedy made the headlines. Six years after two boys were given to the wrong parents at Ba Vì District Hospital in Hà Nội, DNA tests confirmed what the parents of one child had long suspected.

Obviously, there is no ideal solution in such cases. But why the mindset that there is only one “correct” solution?

If you want to see how wrong this solution can be, just watch the documentary that was made on the case in Bình Phước.

Watch the anger, anxiety and uncontrollable emotions of the S’tieng ethnic mother when the other couple tells her the truth, the endless tears that flow as the ceremony is held to return the children to their true families.

Most of all, listen to the heartbreaking cries of the little girls when they are separated from their “wrong” parents, who are basically strangers. Consider the blank, empty look on the biological child of the S’tieng mother, a woman worse off in the poverty stakes.

The psychologists and their insights are conspicuously absent.

In Ba Vì, Phùng Giang Sơn wanted his biological child, Đỗ Nhật Minh, back immediately, but the "wrong" mother of his child, Vũ Thị Hương, found it hard to accept the truth, although she’d been divorced by her husband on suspicions of infidelity.

Forced to leave Hương for his biological family, six-year-old Minh cried his heart out: “Mommy, help me! Don’t leave me!”

Now, imagine having to let go of our kids, and their crying out in similar fashion. I cannot. I would die, literally.

So imagine what Hương must be going through. She wanted time, for her son and herself, to adjust to the truth and learn to accept it.

Instead, she received insulting messages from Minh’s “real” family for not returning him quickly, and bad words from acquaintances for not taking her “real” child home immediately.

I cannot imagine that people can be so cruel. Why didn’t Sơn think of the pain of the child that he and his wife had brought up for six years?

And the children’s responses were a categorical “No”, when asked if they wanted to go to their biological parents. What makes the “real” parents think that their children can come to love them really, when they can ignore the child’s pain to such an extent?

In fact, shouldn’t the main question in such tragic cases be: what’s the best solution for the children?

Sophie Serrano of France realised a decade later that the daughter she’d raised and loved, Manon, was not her own. After meeting each other, the parents took the heartbreaking decision that their biological children would remain with the other family.

Serrano said this was the only way they could carry on with their lives, for Manon’s place in her heart was untouchable. The daughter, Manon, said what they’d been through had only strengthened their bond, one of “love and trust”.

In South Africa, a boy and girl born on the same day in 2010 were taken home and raised by the “wrong” parents, but the mistake was realised relatively early, 18 months later. The Pretoria High Court decided the children must stay with the families who raised them as adopted parents.

"It is not a matter where anyone can say they’ve won. It is a matter which must, at the end of the day, benefit the children," the court said.

This makes far more sense to me than what has happened in my own country.

So I found the ceremonies to “return the children to their families” a tragedy that had descended to farce – the handing over of “compensation”, flowers, teddy bears and smiles from the hospital leaders congratulating the two families for having “more relatives now”.

The mothers were not smiling.

They could not stop crying.

They are adults. What about the children?

When one father in the Ba Vì case pointed out that the diaper of the child given to him by the hospital was different, the nurse told him “It’s just a different diaper, but not a different baby. What do you think? If we give you the wrong child, we’ll go to jail!”

No one has been jailed.

But we, as a society, have failed. VNS