Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

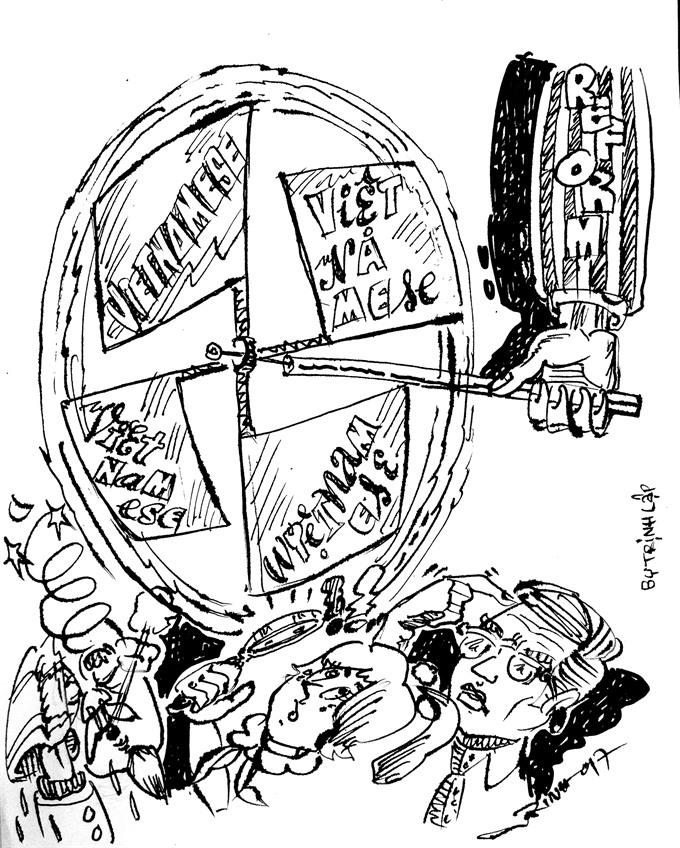

Over the few past weeks, linguist Bùi Hiền has become an internet sensation, not just in Việt Nam, after his paper suggesting a new way of recording the Vietnamese language rocked the worldwide web, touching the nerves of almost all the people who speak Vietnamese.

|

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

By Nguyễn Mỹ Hà

If you are a trained linguist and teach at a university all your life, chances that you become famous are quite low.

If you are really good and you have found or done something remarkably interesting, then may be your students will read your books and discuss them in your class. But people beyond the academic world would have little or no interest in what you find really fascinating.

Internationally, the only linguist who’s known well beyond immediate academic circles is Noam Chomsky, professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a famous political dissident, theoretical linguist and cognitive scientist, who, at the height of the American War visited Hà Nội for a week and lectured at Bách Khoa University, today’s University of Technology.

But over the few past weeks, linguist Bùi Hiền has become an internet sensation, not just in Việt Nam, after his paper suggesting a new way of recording the Vietnamese language rocked the worldwide web, touching the nerves of almost all the people who speak Vietnamese.

Almost everyone felt they had something to say about the paper that was presented at a conference recently, and later written up by some online newspapers.

Bùi Hiền, 83, former Vice Director of the Hà Nội Teachers University and Associate Professor of the Russian Language Department, started his studies more than 20 years ago.

He said he had noticed some indiscrepancies in the way Vietnamese consonants are written at present. For instance, one sound, say /k/, may be written using c, k or qu. This can be very confusing for users, for both Vietnamese and foreign learners of the language. As a result, typos have become quite common.

“It’s my lifetime’s work,” Hiền said in a recent interview, “I’ve placed all my energy and passion for the language in this paper. No one made me do it, but I felt the need to improve the way we write it and save.”

‘Saving resources’

Hiền claims that if the new dictation rules he proposes are applied, less words will be used, saving more paper, time and energy. “At this time of rapid growth, saving resources matters most.”

And this is not all that he wants changed. “The recording system of Vietnamese vowels also needs to be upgraded,” he said. “It’s very confusing as it is.”

Hiền presented his proposals at a linguists’ conference and received mixed reviews. But since his chart was published by an online newspaper, the bouquets and brickbats have flown thick and fast.

“He’s crazy,” wrote one person on Facebook. “There are other urgent needs to be addressed, than to dig all this up now.”

As it happens these days, a new app cropped up, showing how your proper name would look with the new way of writing.

Rarely does an academic paper receive so much public attention, criticism and specific peer reviews.

The degrees of criticism have varied from the posting of elegant, beautiful Vietnamese poems, verses, famous statements by scholars or poets, to sheer vulgarity deployed in the name of protecting the beauty and clarity of the Vietnamese language.

Dr. Ngô Như Bình of the East Asian Languages and Civilisation Department at Harvard University told zing.vn that he supports improvements in how the Vietnamese language is written. “I believe that changes need to be made, but steps must be taken really carefully and slowly.”

He noted that script improvements have been made in other languages – in Indonesia in 1972, in the Netherlands in 1980 and 2005, in France in 1990, in Norway in 1981 and 2005, and in Germany, Austria and Switzerland in 1996.

Already happening

Prior to Hiền’s paper, the internet and chat-rooms have already come up with shorter ways of recording the Vietnamese language. It’s not shorthand, but it enables people to have their writing keep pace with their thoughts. Adults would find it difficult, if not impossible, to decipher the “teencode” that many young people use these days.

“I’m for the shorter and more effective way of communicating online,” a professional writer in her mid 30s said. “But I will defend all the beauty and clarity of the literary Vietnamese language. It makes a difference.”

Over the course of history, from the 10th to the 17th century, the Han script was used for scholarly and administrative purposes. Then Việt scholars began to find the script wanting in its ability to fully record the Vietnamese language, so they invented the Nôm script, which used Han letters.

In the 17th century, western missionaries, most notably Alexandre de Rhodes, used Latin alphabets to record the Vietnamese language, and we use them to this day.

The first Việt-Portuguese -Latin dictionary was first published in 1651, but it was not until the edition of 1772, 171 years later, that the Vietnamese language began to look like what is currently in vogue.

So if we look at the longer story, the Vietnamese language has been growing and it’s not the same as it was two centuries ago.

Dr. Bình of Harvard added that he had not seen any suggestions in Prof. Hiền’s paper on recording Vietnamese vowels.

“In my presentation in March 2018 at a linguist conference, I will present my studies on upgrading the vowels,” Hiền said.

While bowing to the inevitable, I for one, would prefer to keep the Vietnamese language the way I’ve known it all my life. I am confident that I am not alone in nursing this desire.

But the future belongs to younger people. If they keep using language the way they do now, which is typing on a computer screen, sending emails at work and voicing their opinions in chatrooms, via Facebook and twitter posts, then maybe the language has already “evolved” and all linguists have to do is to systemize what is already happening.

It could be that the Vietnamese language will take new forms, maybe long after I and others of my generation are gone, maybe earlier, but my breath is not bated.

I’ll just continue using the Vietnamese that I grew up with. For life. — VNS