Sunday/Weekend

Sunday/Weekend

Just south of Hà Nội lies Chuyên Mỹ Commune, where generations of artisans have transformed humble shells into shimmering works of art. As global tastes shift, this thousand-year-old mother-of-pearl inlay craft is evolving – blending ancient skills with modern flair to shine on the world stage, writes Bùi Quỳnh Hoa.

|

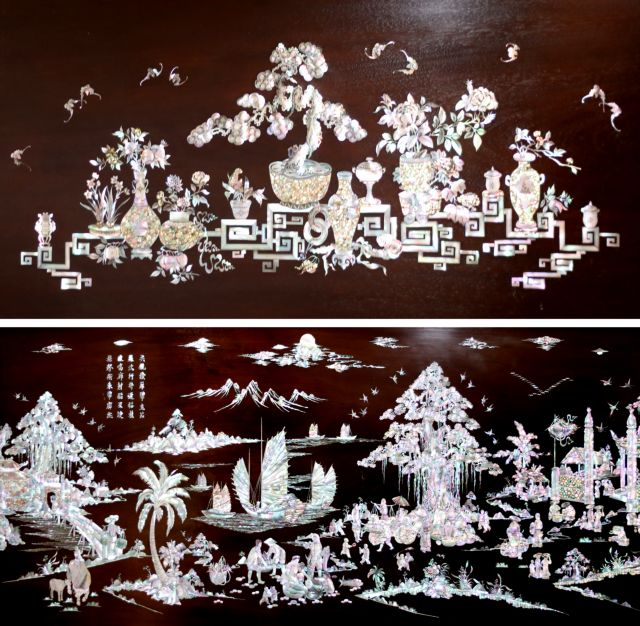

| Decorative patterns in Chuyên Mỹ’s mother-of-pearl inlay artworks are vivid and soulful. VNS Photo Đoàn Tùng |

About 40km south of central Hà Nội, where the city noise gives way to the gentle scent of lotus flowers and birdsong, lies a village that shimmers with centuries of craftsmanship.

Chuyên Mỹ Commune in Phú Xuyên District is not just a peaceful countryside escape – it is the cradle of one of Việt Nam’s most exquisite handicrafts: mother-of-pearl inlay.

Here, tradition is not only preserved but lived. The hands that shape its beauty work quietly in modest workshops, behind bamboo-framed windows and lacquered panels – pieces of iridescent shell coming together to tell stories older than memory.

On a breezy summer morning, the road to Chuyên Mỹ is lined with blooming pink lotus ponds and vibrant flamboyant trees. The early air carries a hint of lake water and lacquer. There is a stillness here that makes time feel paused.

But listen closely, and the rhythmic tapping of chisels reveals the village’s pulse.

|

| Master artisan Nguyễn Xuân Dũng meticulously works on a picture with mother-of-pearl inlay. |

Inside a small workshop, Nguyễn Xuân Dũng, whose family has practised this craft for five generations, bends over a wooden panel. In his fingers is a tiny fragment of mother-of-pearl.

“This work takes patience, but the result speaks for itself,” he says, his eyes never leaving the shell as he guides it into place. Around him, dozens of trays glimmer with abalone, mussel and conch shells, waiting to be shaped into history.

A craft carved from time

The art of khảm trai, inlaying mother-of-pearl into wood, has been practised in Chuyên Mỹ for over 1,000 years. According to village elder Nguyễn Phú Chiến, the origin of the craft dates back to the 11th century.

“Our village worships Trương Công Thành, who is said to be the founding father of this craft,” Chiến says.

“He was a general under national hero Lý Thường Kiệt. After retiring from military life, he spent his days in nature and stumbled upon the beauty of river shells. That was the beginning.”

From decorative altar panels to grand furniture, the art flourished under dynasties and weathered wars. Through it all, the villagers held fast to their chisels, protecting not just a trade but an identity.

|

| Creating inlaid artworks takes time and patience, but the result speaks volumes. |

Creating a mother-of-pearl inlaid piece is nothing short of alchemy.

“There are six main steps,” Dũng says. "First, we sketch a design on tracing paper, then transfer it onto the flattened shells. These outlines are carefully cut. Then comes the wood carving, where we prepare space for each inlay. After that, everything is sanded smooth, polished and painted to bring out the shimmer. Finally, the panel is coated in black lacquer or varnish.”

The process can take days or even weeks, depending on the complexity of the design. Materials come from across Việt Nam and abroad, including large, luminous yellow-lip pearls from Singapore and rare red snails used in royal-style motifs.

“The most prized shell has the lustre of a rainbow,” Dũng says. “Each fragment is like a brushstroke of nature’s palette.”

One hallmark of Chuyên Mỹ's technique is precision. “We don’t allow gaps between inlays. The fit must be exact, as if the shell grew there,” he says.

Each scene — a dragon in flight, a scholar beneath a pine tree, a mother carrying her child — is steeped in symbolism. “It’s not just decoration,” Dũng explains. “It’s storytelling. It’s our history in shell and wood.”

|

| From different angles, Chuyên Mỹ’s inlaid artworks reveal shifting shades and colours. |

For generations, Chuyên Mỹ’s craftsmen produced ceremonial furniture, altar panels and classical paintings inspired by legendary tales.

But tastes have changed.

“Young families no longer want the bulky, ornate furniture of their grandparents,” artisan Vũ Đình says. “They want something that fits in modern homes – elegant, functional and global.”

And so the village has begun to transform. Over the last decade, artisans have introduced new product lines: minimalist jewellery boxes, portrait inlays and sleek home decoration. Exports now reach Japan, the Netherlands, the UK, the US and Russia.

“We still keep the soul, but we evolve,” Đình says.

Nguyễn Đình Hân, chief of Chuôn Ngọ Hamlet, puts it simply: “When foreigners admire our work, it reminds us that this tradition has a place in the world.”

This evolution didn’t come easy. Many artisans still use hand tools, and each inlay is unique. Competing with mass-produced items, often imported, remains a challenge.

“Customers today prefer beauty, but also practicality,” Đình adds. “It forces us to improve, not just copy the past.”

Tradition meets technology

In 2023, all seven hamlets of Chuyên Mỹ Commune were officially recognised as traditional craft villages by the Hà Nội People's Committee [Administration]. Over 80 per cent of the commune’s nearly 3,000 households still participate in the craft, and 15 master artisans hold city-level honours.

But sustaining the industry requires more than skill – it needs marketing.

Nguyễn Trung Hội, chairman of Chuyên Mỹ People's Committee, says digital platforms have become a lifeline.

“We collaborate with trade promotion centres and organise product exhibitions, both offline and online, and we began training families to livestream their sales on Saturdays,” he says.

The results are striking. “In just the first four months of this year, online sales exceeded VNĐ70 billion (about US$2.7 million),” Hội says.

“Families now invest in photography, lighting and digital branding. Online commerce helps us reach beyond the village, even beyond the country.”

|

| Young artisans totally dedicate themselves to their work inside a small workshop in Chuyên Mỹ Commune. |

Even as the village modernises, its heart beats in the hands of those who remember its roots.

Duy Hải Phát, a master artisan in Chuôn Ngọ, reflects on the balance between progress and preservation.

“Machines can make work faster, but they cannot make it soulful,” he says. “A handcrafted piece has breath — you can feel the maker’s intention.”

Phát and others now partner with universities and cultural institutes to document the techniques of inlaying, while offering design workshops to younger generations.

“We tell the youth: innovate, but remember. Your hands are writing the next chapter of a thousand-year story,” he says.

Inside another family workshop, Lâm Văn Tứ gently wraps a jewellery box bound for a customer in Singapore. Next to him, his father polishes the surface of a tea cabinet inspired by 19th-century designs. They work side by side, quietly, in synchrony.

“Each shell we use carries a piece of us: our past, our patience and our pride,” Tứ says.

As the sun sets over the lotus ponds of Chuyên Mỹ, its lacquered panels catch the last golden light. The inlays gleam, unmoving yet alive, whispering stories through shimmer and silence. In this village, tradition does not stand still. It glimmers forward, one shell at a time. VNS