Sunday/Weekend

Sunday/Weekend

|

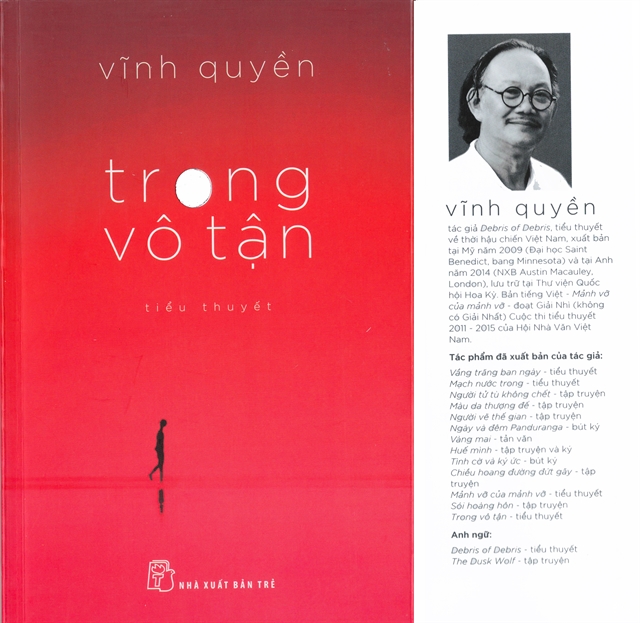

| The cover of Trong Vô Tận (Inside Infinity), a novel by Vĩnh Quyền. |

By Linh Do

In his latest novel Trong Vô Tận (Inside Infinity), writer Vĩnh Quyền offers a sophisticated genealogy of Việt Nam which is at once familiar and also new.

Like many stories of origin, Quyền’s genealogy, which was published by Trẻ Publishing House, sketches a patriarchal state built by devoted mothers and courageous fathers who fight to the death to defend their country and pass it down to their sons.

This hard masculine style is characteristic of Quyền, a journalist and writer whose previous novel, Debris of Debris (Mảnh Vỡ Của Mảnh Vỡ) about post-war Việt Nam, was first written and published in English before it went on to win a second prize (in a contest without first prizes) at the Việt Nam, Writers Association’s 2011-2015 Novel Prize.

Trong Vô Tận features Việt Nam’s troubled history and somewhat justified drive for nationhood. Việt Nam, is a small but proud state which has to constantly defend itself against superpowers such as China and France.

The pride of Việt Nam is encapsulated by Quyền’s unnamed narrator: the heir of the royal Tôn Thất family, a long line of patriotic swordsmen, artists and intellectuals living in Huế, the ancient seat of the Nguyễn Dynasty.

Raised by a loving mother and stepfather, the narrator goes on a journey to visit his dying biological father, with whom his mother earlier broke up because he couldn’t forget a former lover.

In a 10-day physical and psychological journey, the narrator travels back in time to connect with the cultural legacy of his father, grandfather and other male ancestors who, despite great odds, created a nation, and have many values to share.

One value comes from a short story written by the narrator’s grandfather, who was a painter. In the tale, a painter uses his last breath to draw an almost life-like red cotton tree masterpiece for a devoted patron. Another value is taught by the great grandfather, a royal court’s swordsman who carried out dangerous tasks against the French for Emperor Duy Tân, and who learned it wasn’t martial arts skills, but the overcoming of fear, that made a master.

These well-chosen values about talent and courage are woven into an intricate stream-of-consciousness narrative in which the first-person voice of 'I' passes back and forth between the narrator, his father and other male ancestors, all of whom appear at the age of 25.

It’s men teaching men, directly or indirectly through books and art, the love of culture and country. In these male relationships, the prodigal son’s motif stands out. Sons are often seen breaking away from family constraints in their young years only to return to their fathers’ forgiving arms at last.

In this genealogy, which one had better read with a pencil in hand to note down who is whose father, Quyền provides numerous interesting observations about the distinctiveness of Vietnamese culture vis-à-vis China.

For instance, the word sơn hà which means 'country' in the Han Chinese language, is composed of sơn, meaning 'mountain', and hà, meaning 'river', because Chinese geography boasts high mountains and long rivers.

Việt Nam, by contrast, has a long coastline hugging its land from north to south. This combination of land and sea is manifest in the Vietnamese word for 'country': đất nước. The novel is explicit in its criticism of China’s hostile deployment of its HD-981 oil rig in Việt Nam’s exclusive economic zone and continental shelf on May 2, 2014.

Quyền’s political vision could easily persuade one but for the patriarchal aspect of his nation state. In the heroic effort to build and protect Việt Nam’s independence, women seem to have to sacrifice too much. Not only the narrator’s mother, but other women also have to share their men.

Concubinage is an integral part of the patriarchal state in which the first wife suffers the hardest burden. She stays at home like a shadow to care for her husband’s family while he is free to explore the world and find true love in other women, as in the case of the narrator’s great great grandfather, painter Tôn Thất Cẩm Thi.

Ultimately, however, Quyền is a nuanced writer whose text reveals the imperfection of the solidarity that his narrator wishes for. There are two elusive characters that exist on the fringe of the narrator’s all-encompassing patriarchal consciousness, refusing to be co-opted.

One is Hoàng, a homosexual friend whose advance the narrator rejects and who ends up committing suicide out of irreconcilable conflicts with his times. Another is Nhàn, a spiritual girl who rejects the narrator’s advance.

The hypersexual Hoàng and ethereal Nhàn occupy the two extremes whose middle is the narrator, who, despite a long family tradition and ponderous last name, is, after all, just a graduate student with an ambitious master thesis in history titled "Đại Nam - An East Asian Superpower" which argues that Việt Nam, was an East Asian superpower by the time the French came.

The narrator’s ancestors also appear in their early manhood, suggesting an inherent vulnerability. Quyền further explains that in history, the last name Tôn Thất which meant 'honourable family' could be bestowed on both royal blood and ordinary people who made great contributions and so deserved the name.

The idea of the patriarchal state then has a certain openness. This light masterstroke gives Vĩnh Quyền’s novel its grace. Whether Việt Nam was, or should be, an East Asian superpower, and what are the relationships between men and women and everybody in between in this political vision are questions yet to be definitely answered. VNS