Society

Society

Bribes have become increasingly accepted by Vietnamese people, according to results of a seven-year study released by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) last month.

|

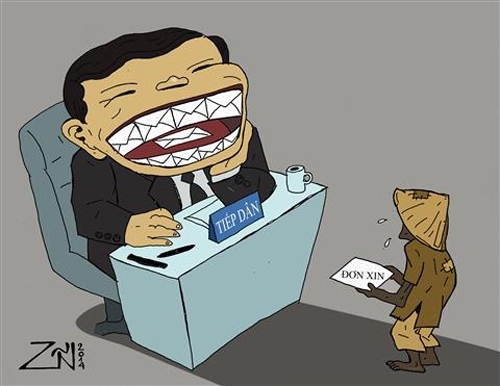

| ‘Envelope Smile’ – the first prize-winning cartoon from Việt Nam Press Cartoon 2014 organised by Thể Thao & Văn Hóa (Sports & Culture) newspaper. |

Nguyen Khanh Chi

Viet Nam News A mother of two was looking for a public kindergarten. Through an acquaintance she met the principal of a kindergarten in the city centre known for its prestige. Along with the three-year-old child’s CV, she brought an envelope containing VNĐ5 million (US$220).

After hearing that one needed to pay a price to get a seat, she went ahead with sending $220. After a weeklong wait, she got a nod.

The 36-year-old Hanoian who asked to remain anonymous said her act simply helped ‘grease the wheels’. She said she had paid a similar amount to receive a place for her elder son in a primary school’s first grade some years ago.

“My friends, colleagues and next-door neighbours often speak about the so-called ‘greasing money’ when it comes to education and health services, and other administrative procedures,” she said.

“When I gave birth to my children, whenever the hospital nurses came to pick them up for a shower, I put VNĐ20,000 (about 90 US cents) into the nurses’ pockets to make sure she would take good care of them.”

The unofficial payment she speaks of has become increasingly accepted by Vietnamese people, according to results of a seven-year study released by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) last month.

Research on the efficiency index of Việt Nam’s public administration, which surveyed nearly 75,000 people across 63 cities and provinces, reveals that the number of people speaking out about ‘greasing money’ in HCM City went down from 12.5 per cent in 2011 to only 2.3 per cent in 2015, whereas none of those surveyed in Hà Nội reported corrupt acts to the police in 2015.

Deputy Head of the municipal Department of Construction Đỗ Phi Hùng said worrying problems still exist, such as complicated procedures, bureaucrats seeking private gains and people wasting lots of time going back and forth when it comes to service provision.

In half of the provinces surveyed in the Việt Nam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI 2015), just 28 to 47 per cent of respondents said they did not have to pay bribes when accessing public health care at district hospitals. Similarly, only between 36 and 59 per cent of those asked claimed that bribery does not take place at primary schools.

The Penal Code and related laws stipulate that any person who abuses their authority to receive money or material benefits in any form valued at VNĐ2 million or more shall be accused of taking bribes.

The average amount of greasing money that respondents admitted to paying for administrative procedures since 2011 has far exceeded this amount, says PAPI 2015, released in April.

The index indicates that between 2014 and 2015, the tolerance of bribe amounts surged, with victims of corruption saying they would not report the case unless the bribe being asked for reached about VNĐ24 million ($1,070).

“Those figures reflected an increasing tendency of Vietnamese in getting used to corruption,” said UNDP policy analyst Đỗ Thị Thanh Huyền.

“Corruption still exists and is getting worse despite determined efforts from the highest level to eradicate it. If the corrupt acts persist, people are likely to fall into depression, increasingly drawing the poor away from social development while increasing feelings of injustice and exerting negative impacts on public confidence in those in power.”

According to the 2013 Global Corruption Barometer – Views and Experiences from Vietnam citizens, only 38 per cent of Vietnamese citizens surveyed said they were willing to report an incident of corruption, the lowest among surveyed countries in Southeast Asia.

“The figures show that when the level of corruption tends to rise in Việt Nam, Vietnamese people seemingly are getting more used to corruption and easily accept corruption,” said Đào Nga, executive director of Towards Transparency.

“The phenomenon is worrying because it might lead to the ‘normalisation’ of corrupt acts in society.”

A joint study by UNDP Việt Nam and the National Economics University entitled Local governance, corruption and public service quality: Evidence from a national survey in Vietnam shows that while corruption may benefit a smaller number of people holding public offices, it hurts society as a whole.

In basic areas such as health and education, corrupt acts lead to higher consumer costs and destroy personal integrity. Other consequences include the breakdown of social trust, followed by crime and social vices.

In a report released last month reviewing 10 years of implementing the Anti-Corruption Law, the Government Inspectorate found that over 92 per cent of ‘hush money’ was lost.

Known damages caused by corrupt cases and practices over the past 10 years reached VNĐ59.8 trillion ($2.7 billion) and more than 400ha, but only a tiny sum of VNĐ4.7 trillion ($209 million) and 219ha of land were recovered to the State budget.

Corruption is seen as a market, but in this market demand comes first. If public bodies and officials say “no” to unlawful money, ‘customers’ shall not have to ‘grease the wheels’, said policy analyst Huyền.

“More importantly, the whole society must demand information transparency and a stop to all corrupt practices. Surely enough, if there is no demand, supply will find no place to proceed,” she said.

During a recent meeting with Đà Nẵng authorities, Dennis Curry, assistant country director at UNDP Việt Nam, emphasised that "to move towards facilitating responsive and accountable local governments, it is necessary that voices of citizens and businesses are heard, their demands are met and their concerns are addressed."

Vice Chairman of HCM City’s People’s Committee Trần Vĩnh Tuyến also asserted that “the fight against corruption requires citizens’ determination not to pay bribes.”

“How can we stop corrupt acts if one is willing and even advises others to pay ‘greasing money’?” he said, adding that the city had created mechanisms for direct dialogues with local enterprises and hotlines to receive residents’ feedback.

A variety of legal documents have been put in place to encourage people to report corruption and to protect those who come forward to report corrupt acts. These include the Anti-Corruption Law, Decree 47, which guides the implementation of the law; the Law on Denunciation 2011; the Government Inspectorate’s Circular No 07 from 2014, which allows anonymous written complaints to be accepted; and the Government Inspectorate and the Ministry of Home Affairs’ Joint Circular No 01 from 2015 regulating rewards for individuals who have denounced acts of corruption.

Experiences of developed countries have shown that transparency, accountability and participation significantly reduce corruption which in turn helps increase access to and improve the quality of public services, said the National Economics University and UNDP Việt Nam research. — VNS