Environment

Environment

|

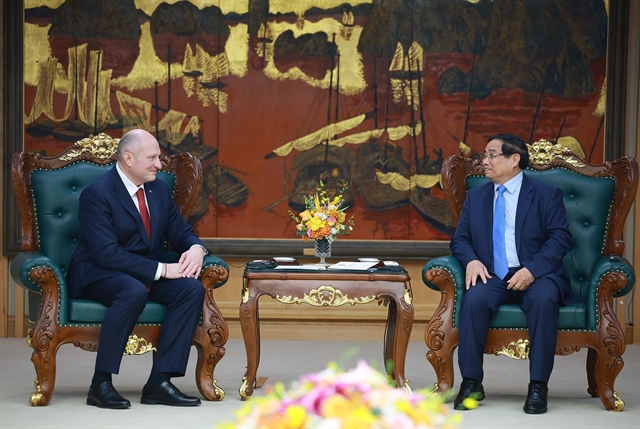

| Workers classify waste in the southern province of Bình Dương. — VNA/VNS Photo Dương Chí Tưởng |

HÀ NỘI — Waste sorting at the source is a crucial step in environmental protection. Although it is now legally mandated, enforcement remains challenging in many areas.

Việt Nam generates an estimated 67,000 tonnes of waste daily, with urban areas accounting for around 60 per cent.

Most waste is still disposed of in landfills, which poses significant risks to both the environment and public health.

To address this, the 2020 Law on Environmental Protection requires domestic solid waste to be classified into three categories: recyclable waste, food waste, and other household waste.

The law on waste sorting officially took effect at the end of 2024.

However, many people—including waste collectors—still lack awareness or a clear understanding of the regulations and how to implement them.

Trần Thị Thảo Trang, a resident of Mỹ Đình Ward in Nam Từ Liêm District, Hà Nội, said her family’s waste disposal routine remained unchanged despite the new regulations.

"When I read in the newspaper that people could be fined for not sorting their rubbish, I asked the local garbage collector, but she said there were no instructions yet. Waste collection is the same as before," Trang said.

Associate Professor Lưu Đức Hải, Chairman of the Việt Nam Association for Environmental Economics, noted that while authorities were focused on managing household waste, construction waste—which accounts for 15-16 per cent of urban waste—remained largely overlooked.

Hải explained that waste generated in households, apartment buildings, and businesses consists of multiple types—at least 30 to 50 categories, with plastic alone having six or seven varieties. For effective recycling, these materials must be sorted at the source rather than mixed together.

"Waste can be a resource if sorted properly at the point of disposal. However, once collected and left in landfills for two to seven days, it simply becomes waste to be burned or buried," he said.

Several pilot waste-sorting initiatives are currently underway in Hà Nội and HCM City, funded by foreign organisations or the State budget. However, Hải said these projects had yet to succeed due to a lack of specialised collection vehicles, inadequate storage facilities, and limited public awareness.

He added that even with a modest estimate of US$50 per tonne for waste collection, transport, and treatment, Việt Nam spends approximately $3.35 million every day on managing domestic waste.

This is no small expense for a developing country like Việt Nam.

Sorting waste at the source increases the volume of materials available for recycling, laying the foundation for a circular economy where waste is transformed into resources that can be fed back into production.

The regulation also plays a key role in environmental protection, reducing the amount of waste requiring treatment and helping Việt Nam move towards a zero-emission economy by 2050.

Turning policy into practice

Associate Professor Lê Hùng Anh, Deputy President of the Việt Nam Association for Clean Water and Environment and Director of the Institute of Science, Technology and Environmental Management, noted that waste classification had yet to be properly implemented in cities like Hà Nội and HCM City.

"Local authorities have not fully committed to enforcing waste sorting at the source. In reality, most people are unprepared, and many are still confused when asked about waste classification—some are even unaware of the regulation," Anh said.

Associate Professor Nguyễn Thị Ánh Tuyết, Director of the Institute of Science and Environment at Hà Nội University of Science and Technology, pointed out that although the law is in effect, it has yet to become a routine part of daily life. She stressed the need to assess existing challenges and determine whether supporting legal documents are appropriate.

Implementation, she suggested, should be phased in gradually.

Under the Government’s Decree 45/2022, households and individuals who fail to classify domestic solid waste face fines of VNĐ500,000-1 million ($19-39). Tuyết argued that while the penalty is significant, it is difficult to enforce given the current lack of infrastructure and public readiness for waste sorting.

"My concern is not just about imposing penalties but how to enforce them fairly. Some households have the space to sort waste, while others do not. Public awareness also varies. Any fines should be applied in a way that takes these differences into account," she said.

Sorting waste at the source is a crucial step in environmental protection, but for the regulation to be truly effective, it requires coordination across all levels of government and the community.

Experts stress that the issue is not just about forcing households to comply—it requires a comprehensive strategy to build a well-functioning and coordinated waste-sorting system. — VNS