World

World

|

| Under current Korean law, adoption records are permanently sealed after an adoptee’s death — even from their own children. PHOTO ILLUSTRATION |

SEOUL — Adoptee advocacy groups from all over the world gathered outside South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in Seoul on April 10, calling for a new round of investigations – and legal accountability – over systemic malpractice in the country’s intercountry adoption programme.

The demonstration comes around two weeks after the independent commission on March 26 announced that it had identified human rights violations in 56 of the 367 adoption cases submitted since the investigation began 2022. The adoptees had been sent overseas between 1964 and 1999 to countries including the United States, France, Denmark and Sweden, according to Reuters.

As at March 26, the commission said it had completed investigations and issued reports for 98 cases – only about 26 per cent of the total. Of those, 42 were dismissed due to “insufficient evidence”, leaving just 56 cases officially recognised.

The remaining 267 cases have already been investigated, but their final reports are still being written. However, with the mandate for this TRC – South Korea’s second in history – set to expire on May 26, it remains unclear how many of these will result in official acknowledgment before this commission’s mandate ends.

A TRC official cited the “sheer scope and complexity” of the cases as the main reason for the delay.

“Our message is simple,” said Mr Peter Moller, a lawyer born in South Korea and adopted to Denmark, who is co-founder of the Danish Korean Rights Group. “If all 367 adoptees cannot be recognised, a new commission must and shall be established – one that allows new applications.”

Moller stressed that the burden of proof should not fall on the adoptees themselves as victims whose records were deliberately destroyed or falsified; in other words, whose human rights were violated through illegal adoptions.

“That’s how the rule of law works,” he said.

Advocates are also pushing for criminal prosecution – not just fact-finding.

“This is no longer just a matter for investigation,” said Min Young-chang, co-chair of the Adoption Solidarity Coalition. “It’s a matter for prosecution.”

Min argued that missing documentation itself signals wrongdoing, not a lack of evidence. “Information that doesn’t exist – that is the evidence,” he said.

He also called for certain cases to be referred to prosecutors and the National Assembly, if necessary.

Other speakers at the rally shared stories that reflect the long-term effects of South Korea’s adoption policies.

Cho Min-ho, director of the Children’s Rights Solidarity, recounted being labelled an orphan by the state despite having living parents. “I was intentionally made into an orphan,” he said, condemning the erasure of identity as a violation of both Korean constitutional rights and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

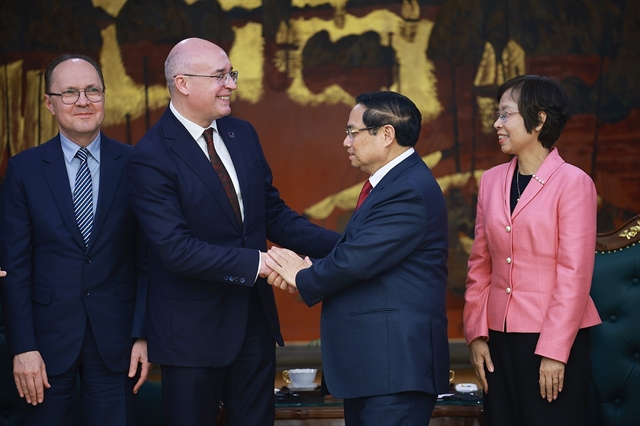

Maite Maeum Jeannolin, a filmmaker and daughter of a Korean adoptee to France, highlighted the lasting consequences for adoptees’ descendants.

Under current Korean law, adoption records are permanently sealed after an adoptee’s death – even from their own children. “We deserve the right to understand it,” she said, referring to descendants’ rights to search for their biological families.

Ben Coz, a Korean adoptee to the US and member of the international network ibyangIN, called access to birth and adoption records “a human right”, citing international child rights law and professional ethics standards.

He encouraged adoptees and supporters in receiving countries to advocate for policy changes at home, noting that more countries, like Norway and the Netherlands, have opened their own investigations.

Many demonstrators said they were unable to apply to the current TRC before the application window closed and are now left without any path to official recognition or redress.

“This isn’t history,” said Mr Min, reacting to recent remarks by TRC chairman Park Sun-young, who called the adoption abuses “a thing of the past”. Min disagreed, saying: “It’s still happening.” — THE KOREA HERALD/ANN