Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

Two similar stories happened in two different northern provinces: one in Thái Bình and the other in Thanh Hóa, but both are stories of true friendship.

|

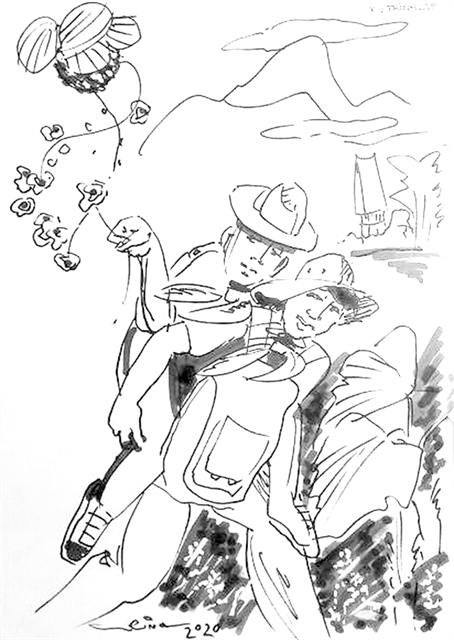

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

by Nguyễn Mỹ Hà

It seems like the whole country has been talking about Ngô Minh Hiếu, a high school student from the northern province of Thanh Hóa who posted a pretty high score at the national university entrance exams but nonetheless failed to get into the prestigious Hà Nội Medical University (HMU).

Bearing a name that means, literally, “filial piety” in Vietnamese, Ngô Văn Hiếu has been true to the ideal, carrying his invalid best friend Nguyễn Tất Minh from home to school and back every day for ten years. Reporters started calling him Ngô Minh Hiếu, squeezing in his friend’s name.

When it was time to apply to universities, Hiếu wanted to become a doctor, in a bid to shed some light on his friend’s condition and help him out. Minh, sharp of mind but suffering from a birth defect that affects all of his limbs except his left hand, wanted to become a computer scientist. They took the entrance exams for the HMU and the Hà Nội University of Technology (HUT) and scored an impressive 28.15 and 28.10 points out of 30, respectively.

But … well … there’s always a paragraph starting with “But” in real life, even when a beautiful life story is involved. The “deadly” high score needed for the HMU was announced, and Hiếu was an agonising quarter of a point short of his dream.

Aware of his moving tale, many people took to social media or online news websites to appeal for a special waiver from the HMU.

“Hiếu’s score was an impressive 28.15 out of 30. Please let him in, the Medical University, so that he can be close to his best buddy Minh and keep their fairytale alive,” wrote one commentator.

But there were others who disagreed. “I believe that if the Medical University took him in, it would be unfair to those who were only 0.05 points short of living their dream. We need to respect the publicly-announced entrance score.”

Entrance exams determine who secures a place at universities in Việt Nam, and the barrier that separates those who pass and those who fail is small yet huge.

If acceptance was based on standardised exams plus a statement of purpose and a personal interview, then the decision could easily factor in character and not be solely based on academic performance.

To bring the “opinion warfare” to an end, Hiếu told the press, “Even if the Medical University offered me a place, I would turn it down. My dream is to become a doctor, not to get into one specific school!”

Such a self-righteous young man; winning the respect of all who know of him.

Hiếu and his friend Minh planned on applying to the two universities in Hà Nội because they are nearby each other and the two could rent a room together. Hiếu could continue to help Minh out and write the next chapter of their long-lasting friendship, set in the big city.

The second choice on his university “wish-list” was the Thái Bình Medical University, which accepted him.

But it involved living in Thái Bình City, 100 km southeast of Hà Nội and his friend, who was to study in the capital.

The HUT, though, promised Minh extra support and assistance while he pursues his studies.

More joy awaited Hiếu, as the principal, Prof Hoàng Năng Trọng, told him the university had decided to waive all his tuition fees.

But an even more moving story came soon after, when it emerged that they shared a common bond.

For Prof Trọng had also “carried” his best friend, poet Đỗ Trọng Khơi, some 30 years ago. “I was touched by your beautiful friendship, because I have my own friendship with someone who is not as fortunate as I,” the professor reportedly told Hiếu.

The two similar stories happened in two different northern provinces: one in Thái Bình and the other in Thanh Hóa, but both are stories of true friendship.

“Your kindness not only helps your friend survive, but also gives him courage and belief in life,” the professor said.

Hiếu was surprised to have heard of this, and visited Khơi in his home.

“Did your friend ever lose faith?” the poet asked when they met. “No, he is very strong and full of a love for life,” was Hiếu’s answer.

Khơi, 60, has a family of his own, with two sons. His wife is a librarian in the city. When he was 11, he suffered a fever and caught polio, which left his legs paralysed.

This was in 1971, and Khơi’s father had already been killed in the war against the US. He was unable to get to school and quickly became bed-ridden. He spent hours listening to a radio his mother had bought him, and the Voice of Việt Nam’s poetry recital programme, “The Sound of Poetry”, became a favourite.

He then started to pen his own poetry.

In 1987, a group of young doctors and medical students from the Thái Bình Medical College came to Khơi’s village. Among them was the young Dr Trọng.

By chance, Trọng read one of Khơi’s poems and wanted to meet the man behind the words, who he knew suffered from a physical disability. Khơi has remembered what Trọng said to him all those years ago: “Keep writing your poems and keep the originals. I live quite near some newspaper offices, and I’ll show your poems to the editors.”

A friendship had begun.

For nearly 40 years now, Đỗ Xuân Khơi has been friends with Hoàng Năng Trọng, and he has also added his friend’s name to his, adopting the pen-name Đỗ Trọng Khơi.

He then asked Hiếu how his special friendship came to be.

“We were neighbours,” Hiếu replied. “Both of our families were poor. His parents moved to work on new land in the Central Highlands. No one took him to school, so he only came off and on. I didn’t want him to miss his studies, so I carried him.”

And so a modern-day fairy tale was written, with the moral of the story being “A friend in need is a friend indeed”.

Prof Trọng told Hiếu, “I was just like you. When I helped out my friend, people would think the help was only going one way. But no, I also relied on him for many things and often needed his help.”

The two now have their own families but have maintained close ties, living just a few hundred steps away from each other. VNS