Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

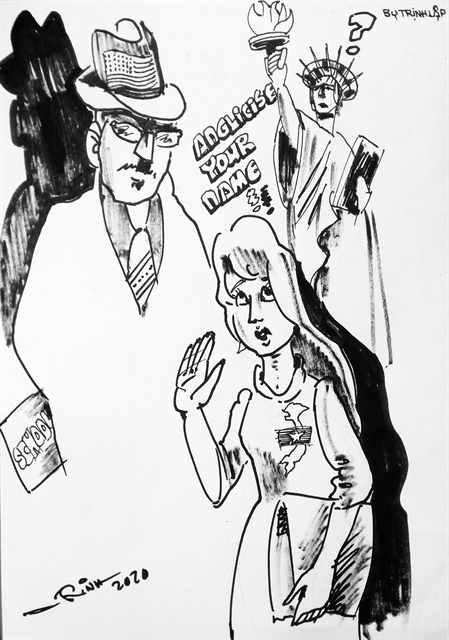

Recent news of a maths professor at a US community college asking one of his students to “Anglicise” her name made headlines around the world, while the offending email was widely shared on social media.

|

| Illustration by Trịnh Lập |

by Nguyễn Mỹ Hà

Recent news of a maths professor at a US community college asking one of his students to “Anglicise” her name made headlines around the world, while the offending email was widely shared on social media. He has been placed on leave pending an investigation.

Initially it seemed to be the usual obstacle many immigrants to the US or elsewhere face: your name may mean something quite beautiful in your mother tongue but absolutely not in English.

Millions of people coming from Asia to Europe or the US change the way their names are pronounced. Whereas people may leave their family names unchanged, their given name can be altered to accommodate new surroundings and culture and make it easier to fit in. Some people pick another name altogether, that’s easier for others to pronounce.

In Vietnamese, the woman’s name Bích Vân means “Blue Cloud” but sounds like “Big Van” in English, so many with the name Vân decide to go with Vanessa.

Dung means “Grace” and is a woman’s name, while Dũng means "Bravery" and is a man’s name. But many people choose to add a Z just after the D (Dzung), as Dung in English is really not that pleasant.

And Thu Nga may translate as “Autumn Moon” but can sound like “Tuna” in English. If you don’t want to change the beautiful name your parents gave you, be prepared to be called "Tuna" in your new home.

In Việt Nam there is a saying, “Nhập gia tùy tục”, meaning when you are in a new family, adapt to their customs, or similar to English proverb "When in Rome, do as the Romans do". Millions of people have done so to make it easier to assimilate.

As did Phuc Bui Diem Nguyen, who used to go by the name May but one day decided to use her legal name, which bears both of her parents’ family names and a two-word given name. Her given name means “Happy Blessing”, which reflects her parents’ joy over her coming into their lives as well as their wish that she experiences a life full of blessings.

Though people who were born speaking English tend to have the world accommodate their preferences, the college student mentioned above asked that she keep her original name, which put the professor out of his comfort zone. His request that she “Anglicise” her name literally meant finding another way to pronounce it or choosing a whole other name. But his insistence that she do so triggered not only the student but also others.

Problems with names are quite common. Staff in the tourism industry often have to ask visitors to repeat their names, and if it has another meaning in the local tongue then they may politely suggest the person temporarily changes it.

Many choose a new name that at least approximates their given name: Vân becomes Vanessa in France and English-speaking countries, Hà becomes Hanya in Russia or Haly in Germany, and Giang becomes Gianna or Gianne in Italian.

In my graduate class many years ago was a girl from Russia whose name was Irina Slutsky. Needless to say, she was advised to change her family name on a regular basis.

At hotels, resorts, and foreign-owned companies in Việt Nam, Singapore, China and beyond, employees may be asked to pick an English name, to make it easier for visitors or international managers to address them. And at international schools, children also take on an English name, to make it easier for the teachers.

It goes both ways, too. Many Americans, Canadians, Brazilians and others who have made a home in Việt Nam have chosen a Vietnamese name. A famous Canadian called Joe went for Dâu (but Vietnamese call him something like Zoe instead), and authored a best-selling book entitled My Name is ‘Dâu’. Footballer Kesley Alves from Brazil picked the Vietnamese name Huỳnh (pronounced in the south, at least, as “Win”).

Another American-Vietnamese man wrote a book entitled John đi tìm Hùng, or “John in search of Hùng”, which shared his tales of returning to his roots and seeking his Vietnamese identity.

Unlike in the West, where parents may name their children after their own parents or someone else in the family tree, in Việt Nam it’s considered unacceptable to give your children your name or the name of your parents.

In the past it was considered unacceptable to even say your parents’ names. You would also never know the names of your grandparents or other elders in the family, and on many occasions new parents opted for the name of a heretofore unknown dead relative, with much consternation ensuing.

There is, indeed, a great deal in a name. More than just what a person is called, it’s also wrapped up in family tradition or parents’ expectations.

Sometimes in Việt Nam it’s a name that reflects when they were born. During wartime, many people were named Thống Nhất (Reunification), Chiến Thắng (Victory), Hòa Bình (Peace), or Hạnh Phúc (Happiness).

So, be considerate and thoughtful whenever you say someone’s name, because you may be confronting not only one person but an unknown world of culture and tradition. VNS