Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

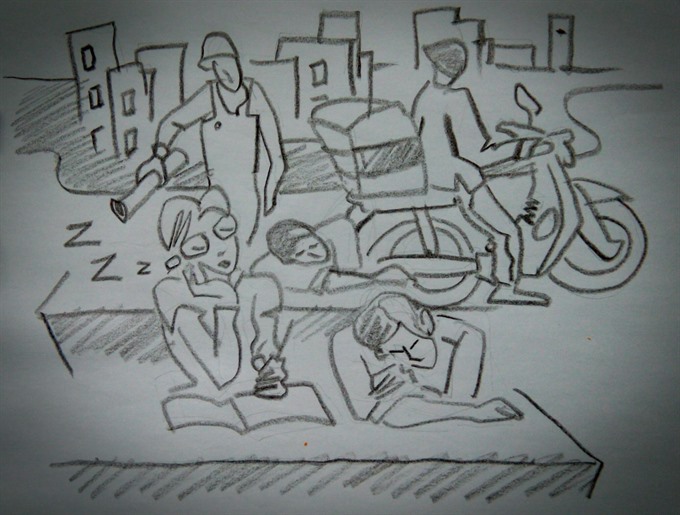

An incident recorded at an eatery for low-income people in District 1 of HCM City last week has raised discussion on the attitudes towards becoming independent of Vietnamese university students.

|

Bảo Hoa

Vũ Tuấn Anh runs an institute that provides soft skills and management training for college students to increase their chances of finding a good job.

He flew into a rage last week on seeing a long line of students queuing up at an eatery in HCM City’s District 1 that offers very cheap meals for low-income citizens. Run by local philanthropists, a meal costs just VNĐ2,000 (9 cents).

“It stunned me,” he said, captioning a photo of the students on his personal social media page. “These young adults, who are in perfect health, should have enough self-esteem not to eat what’s meant for poor, old people incapable of working.

“Getting a part-time job to support themselves shouldn’t be too hard,” he fumed.

The incident sparked discussion on a very important, relevant topic.

Some people agreed with Tuấn, while others said most students, especially those who come from rural areas to study in the city, are poor, and getting a low-priced meal is their way of cutting costs.

While an argument can be made that Tuấn Anh was a bit presumptuous in labeling the students lazybones unwilling to work, it cannot be denied that there are millions of students who don’t work while studying, depending entirely on parents and not assuming any responsibility for their upkeep.

What’s more, this is a situation encouraged in Việt Nam by “helicopter parents” who want their children to stay in their arms forever.

Đỗ Anh Tuấn, father of a university student in Đống Đa District in Hà Nội, doesn’t want his daughter to work because he fears it will interfere with her studies.

“Suppose I let her do it, she would not be making much money anyway,” he said. “And a job, even a part-time one, costs time. I’d rather she remains focused and do well in her formal studies so that she can get a good full-time job when she graduates.”

Minh Hồng, a third-year student at the Việt Nam National University in Hà Nội, has a part-time job at a design company. She applied for the job without asking her parents. “They weren’t so pleased,” she said.

“The job requires me to work every morning, so my parents are worried that it’s taking too much time. They keep telling me to quit.”

A 2015 survey of about 500 students aged 18-22 found 19 per cent working part-time, and another 38 per cent who’d done it earlier. Being a waiter or waitress and tutoring were the most popular part-time jobs, the survey found.

Class consciousness?

I have a friend who used to work as a “ticketing agent” for an art show while she was in the university. Her job involved standing at the entrance of a theatre, talking to any customer that walked in, and persuading him or her or them to buy tickets to the show.

Since most of her customers were foreign tourists, English fluency was a job requirement. Occasionally, she threw in a bit of the French she was studying then. It seemed like a very cool, intellectually interesting and challenging job to me, but this friend didn’t tell her schoolmates what she was doing.

Why not? “Because in order for them not to probe too much I’d have to simply say I am ‘selling tickets,’ and that would sound so lame.”

This got me wondering. If the easiest job to get, and therefore, most preferred, was waiting tables, were the helicopter parents and students that don’t work afraid of losing face, of “being found out” by acquaintances doing menial jobs?

I suspect that there is more than an element of truth in this, especially among the more well-to-do sections of the society.

There are proven benefits of having a part-time job while studying. They earn their own money, gain budgeting and time management skills, get a break from mind-boggling academia, and get a self-confidence boost that can be very helpful no matter what they do in the future.

Class conscious parents and students should understand that working part-time, no matter what the job, will boost real self-esteem, not prop up fake prestige.

So, barring rare exceptions, Tuấn Anh is right. When it comes to self-esteem, students queuing up at charity eateries are way out of line. — VNS