Talk Around Town

Talk Around Town

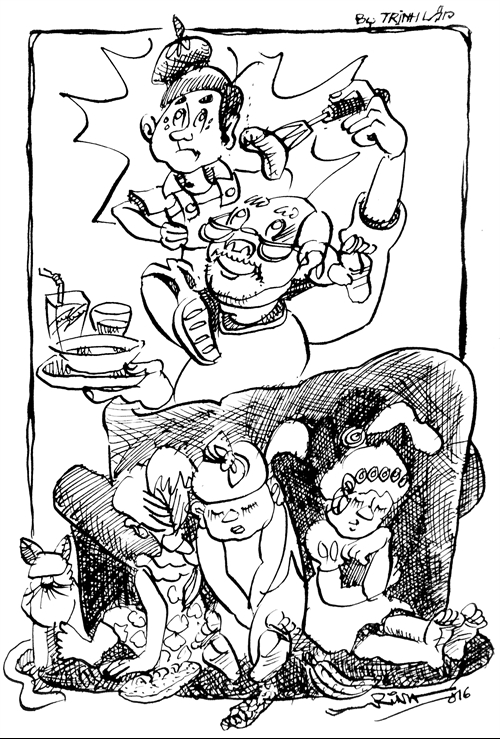

I was in shock at the nasty habit of Vietnamese society putting pressure on new brides to give birth to a boy.

|

by Vanessa Pham M.

Ever since my husband and I returned from an ultrasound session during the 2nd trimester of our pregnancy, I have not been able to forget what I experienced. The news made my entire body and soul cringe, the instant I heard it. As a daughter, as a future mother, and as a woman, I need to express my feelings about what happened.

The ultrasound went fine. Naturally, my husband and I were immensely emotional at the sight of our little bundle of joy moving and jumping inside of me. I couldn’t hold back my tears as the ultrasound images passed before my eyes. (Though I blame my hormones for the crying). We were very happy.

Out of curiosity, I asked the doctor if he could tell the gender of our baby. How surprised I was when he answered me in a way I could not have expected: “Hospital policy forbids me to divulge the sex of your unborn baby, Madam.” “Oh? And may I ask you why?” I asked.

“Too many Vietnamese families decide to... well... get an abortion if the baby turns out to be a girl, Madam.” said the doctor.

I was in shock at what I had just heard. Yes, it’s no secret: I have always known about this nasty habit of Vietnamese society putting pressure on new brides to give birth to a boy.

I know some couples who are still trying to have a boy, after giving birth to only girls. But I did not know the Vietnamese prejudice against girls was this bad. I did not realize that mothers have to give birth to boys at any cost. I was horrified. I was discovering a whole side of my half-Vietnamese roots which I had no clue about before. The realization made me feel intensely sad and somewhat powerless.

I guess the doctor saw my expression. Then he asked if I have Vietnamese citizenship. I told him that I’m a French citizen. To which the doctor replied that he might be able to tell me the sex of my baby after all, but only if my husband agreed to step out of the room.

My husband and I looked at each other for a moment. Then he left the room so the doctor could go ahead and share the precious information with me. As soon as my husband left the room, the doctor turned to me. And as he was about to tell me the baby’s sex, I stopped him.

So far, I had found the situation utterly ridiculous, to say the least. This entire masquerade! I told the doctor that, on second thought, I did not want to know the baby’s gender anymore. I told him I completely understood the hospital policy, and that I respected him for refusing to disclose the gender of our baby.

How can such a foolish and overly dramatic scenario happen? But this is the reality Việt Nam faces. Is not telling the parents a baby’s sex really all we can do to prevent unborn babies being aborted, just because they are not the “right” gender?

In the end, my husband and I decided against learning the sex of our baby. We hope this small, insignificant act on our part will send a message to both our families, our friends, our colleagues, and society as a whole.

How many women have been forced to give up their unborn children, only because they were girls? How many women are still being forced to keep trying until it’s a boy? How many rightful lives were wrongly ended? Too many.

How many women were humiliated and shamed by their peers, by their families, by society -- for being "unable", or for "not knowing" how, to give birth to a boy? Gender does not matter. And it should not matter. It’s not a boy. It’s not a girl. It’s a baby.

And all of this injustice is for what? For the sake of keeping a family name? A bloodline? Even more ironic and saddening is that some of the fingers pointing at women who give birth to daughters belong to other women who suffered through the very same torment themselves.

History sure has a way of repeating itself.

On a separate, but not unrelated, note: if you have a boy, people tend to buy you a ton of blue things with basketballs and Power Rangers on them. If it’s a girl, you can be sure gifts will feature the Pink Panther and Barbie. If you’re anything like my husband and I, you hate the idea of being pigeonholed. Not knowing the baby’s gender forces people to think outside the box and to consider gender-neutral gifts.

Our neighbours and grocers can’t understand why we don’t want to know the baby’s gender. They keep asking me as often as possible if the baby is a boy or a girl.

"Don’t you want to know if it’s a boy?!" they say.

No, we do not want to know.

Not if knowing means there will be a difference in the way we think and feel about our unborn child.

Our decision has met with mixed reactions, to put it mildly. But we are one hundred per cent proud to stand up for our choice. We simply feel blessed at being given the gift of having a child. That is the only thing that matters. VNS