|

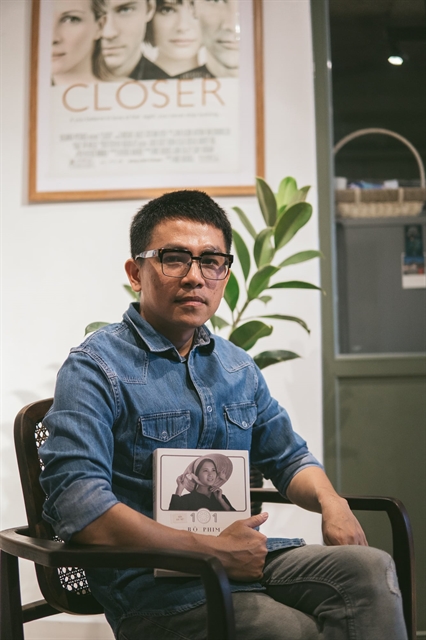

| Lê Hồng Lâm pose with his latest book, "101 Best Vietnamese Movies", which was publisted late 2018. |

By paying heed to directors on TV and in print media, Lê Hồng Lâm, a prominent film journalist, gained a deeper understanding of the film world. Lâm says his first love has always been Vietnamese films since they touched his soul more than any foreign movies. Lâm talks to Thu Vân about how he is optimistic about the Vietnamese film industry as it begins to diversify.

What do you think about the Vietnamese film industry? Is our current film industry, compared to the past (before 1975), improving in terms of quality and depth?

From the perspective of a journalist with nearly 20 years following and writing about Việt Nam’s cinema, I often use the word "transitional" to talk about the Vietnamese film industry. It's a film industry that was born decades later than the rest of the world and matured quite slowly. In each stage of development, there is no inheritance of the previous generation and there’s a lack of diversity. The film industry in the north is completely different from that in the south. And if we compare the current film industry with that of the 1990s, we see no connection or relevance.

However, there are a few directors and actors in each period that are remarkable.

Since the 1990s, film directors returning from overseas, or Vietnamese diaspora, such as Trần Anh Hùng, Tony Bùi and Nguyễn Võ Nghiêm Minh, brought back with them different eyes compared with those working and living here. Over the past ten years, some directors have made records such as Charlie Nguyễn, Victor Vũ, Phan Gia Nhật Linh, Ngô Thanh Vân, and some rare directors who pursue indie and arthouse films such as Phan Đăng Di, Bùi Thạc Chuyên and Nguyễn Hoàng Điệp.

The period with the most achievements for the film industry, in my opinion, is the period from 1975 to the early 1990s, when State cinema partly escaped from its propaganda function, and shifted to describing the real lives of voiceless people. During this period, the film industry to some extent portrayed a true Vietnamese spirit and soul, in both good and bad ways. This is also the period in which the Vietnamese film industry made the best films, in my opinion.

In order for Việt Nam to be able to join developed film industries in the region, what do you think can be done at the management level as well as by the filmmakers themselves?

Việt Nam is still less developed than many other countries with regards to film production, both in terms of talents, technical skills or investment. We do not yet have a generation of talented directors who can build their own identity, but we do have some names that are recognised at prestigious international film festivals, such as Đặng Nhật Minh with When the Tenth Month Comes, which was picked as one of the best Asian films of all time by CNN, Trần Anh Hùng with The Scent of Green Papaya and Cyclo, Tony Bùi with Three seasons, Nguyễn Võ Nghiêm Minh with The Buffalo Boy and Phan Đăng Di with Bi, Don't Be Afraid.

In my opinion, we do not yet have a generation of talented directors who can build their own identity or a clear voice of the country, but we have outstanding individuals more or less known to the world.

I think the Government is now mainly giving the film industry to the private sector and doesn’t have many supporting policies for young talent, nor any policies to preserve the heritage and the values of the past. That leads to rather unhealthy development for the film industry – in the past, we had too many “propaganda” films, now we have too many entertaining films that lack depth, poignancy, or those about social problems or marginalised people. As a matter of fact, we don’t have many films that touch the audience’s hearts and make them think, or make them feel related.

Without the government's supportive policies, some directors have to stop their careers at age 50 and 60 – which is the golden age for many filmmakers.

For some of the new generation directors who are not dependent on the state's budget or major private entertainment studios, they have to walk by themselves and choose a totally different path to find investment from international film investors or funds. And they have succeeded, to some extent. These independent filmmakers may face more challenges and difficulties, but I believe they will create a Vietnamese film identity in the near future.

|

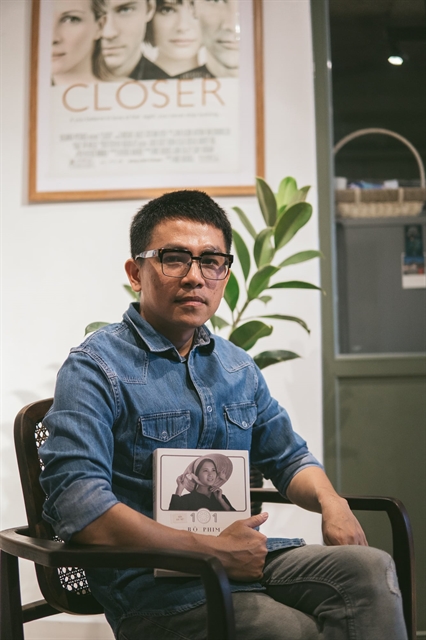

| Lê Hồng Lâm interviews artist Kiều Chinh, one of the most prominent artists of Saigon cinema prior to 1975, who had a successful career in the US since 1975 to date. Photo Vũ Khánh Tùng |

How can Vietnamese film directors keep their national values while having to face fierce competition of Hollywood movies as well as from other Asian countries? Do you think the new generation of local directors will be able to quickly bring Vietnamese films to bigger markets?

In recent years, when the domestic film market flourished, the local film industry has some of the films that made it as the highest-grossing films of the year such as Hai Phượng (Furie), Cua lại vợ bầu (Love Again), Em chưa 18 (Jailbait), Em là bà nội của anh (Miss Granny). This shows that Vietnamese audiences still love Vietnamese films. However, there are still a series of films that failed.

According to my survey last year, the number of films that are box-office flops accounted for three-quarters of the number of films produced in the year. This year's rate is similar. This shows that Viet Nam's film industry is still underdeveloped and investment in the industry is still a gamble.

But I always believe in young directors and am waiting for a generation of filmmakers who have success at the box office but still don't compromise and always carry their personal imprints. Only by doing so can they withstand the fierce competition from Hollywood films or other developed film industries in Asia.

But if a filmmaker does not follow the general public’s taste, will he or she lose the game?

To make a blockbuster, producers and directors have to appeal to the tastes of the mass audience. But that doesn't mean a filmmaker has to lower his criteria to please a part of the audience that only goes to the theatre to be entertained.

On the contrary, filmmakers should aim for elite audiences, true "movie-goers", to conquer them with films that make them feel both entertained and touched. Artistic and experimental movies still need to be made, and directors must still try to make an impression. This makes the ecosystem of the cinema more diverse and interesting.

Indie films in recent times like Song Lang, Nhắm mắt thấy mùa hè (Summer in Your Eyes), Thưa mẹ con đi (Goodbye Mother), may not be successful at the box office, but I think these are good signs for the country’s independent cinema.

The directors of these films have dared to take the adventurous path by telling challenging stories. They might not be welcomed by the general public, but they created a strong belief for true movie-goers that they can have faith in the Vietnamese film industry again.

Besides entertaining films, the Vietnamese film industry really needs to have decent independent films to stay in the minds of viewers. As someone who is deeply entrenched in Vietnamese film, when I look at the signs, I feel quite optimistic. As the market grows, so do the tastes of the audiences in Việt Nam.

You are conducting a research project on Saigon cinema before 1975. Can you share a little about this project?

Saigon Cinema 1954-1975 is my next independent project after the "101 Best Vietnamese Movies" book that I published last year. This is a research project to restore the heritage of cinema once in danger of being permanently lost. This is a challenging project because the resources are scarce and there are not many witnesses.

Fortunately, my project was funded by the British Council's FAMLAB in Việt Nam and I am funded to go to the United States to meet some of the surviving witnesses of Southern cinema at this stage.

Meeting them has helped me with many valuable sources and extremely valuable emotions to revive the atmosphere of this period of the country’s film industry. In my opinion, this is a very special period of Vietnamese cinema that few people know about, especially the young generation.

I hope that through the project, which is expected to be published in a book in early 2020, the young generation of movie lovers will learn more about the golden age of southern cinema. After that, I may start my third project on famous film artists of the time, like a gift to those who contributed to the history of Vietnamese cinema in a period that has already past but will still ring like a bell if we know how to retrieve it.—VNS

Inner Sanctum

Inner Sanctum