Society

Society

October 12 has always been a special day for former staff of the Liberation Press Agency.

HÀ NỘI — October 12 has always been a special day for former staff of the Liberation Press Agency.

It’s even more special this year as they have been bestowed a prestigious title by the State for their contribution to the country’s liberation.

The designation 'Hero of the Armed Forces' was given to the agency by Party General Secretary and President Nguyễn Phú Trọng at the beginning of September.

For former war correspondents who worked at the agency during the American War like Nguyễn Thanh Bền, this State-level recognition means a lot.

“First, it means we deserve it. Second, it means our contribution has been recognised by the State,” he said. “It is an honour, and also a motivation for all of us to work harder to live up to it.

“And it’s also a consolation for those who died, who never lived to see the country’s liberation – those that lost their lives before April 30, [1975].”

The title is awarded to individuals and collectives with outstanding achievements in combat, combat service and work, representing the revolutionary heroism in the cause of national liberation, national defence and the protection of the people.

Founded on October 12, 1960, in the southern province of Tây Ninh, the Liberation Press Agency was the Government’s mouthpiece in Southern Việt Nam from 1960 to 1975.

It reported on the revolutionary movement during this period, guided by the National Liberation Front of South Việt Nam against the American-aided administration in the south.

As many as 240 journalists and staff of the agency died in the war, more than any other media outlet in the country.

Joining the agency in 1964 as a reporter and working until he retired in 1999, Bền knows everything there is to know about covering a war.

He recalls the importance of communicating at all times.

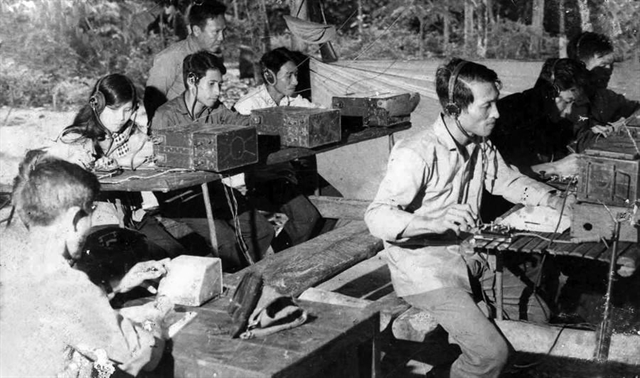

“Our agency had a noble slogan, ‘the non-stop wave’, which indicates the radios that were considered an inseparable part of the reporters,” he said.

|

| “The reason we had this was because if there was no radio signal, it meant something bad had happened to us. It meant we had been caught by the enemy or killed. |

“So we were never allowed to lose communication. It didn’t matter if we were out in the storm or rain when it was time to communicate, we all pulled out the antennas and communicated. Even if we didn’t have anything to report, we still communicated. And we were able to do that throughout the war.”

Lý Văn Tích has vivid memories of being a member of a group of reporters sent from Hà Nội to support their southern colleagues in 1973.

“In July 1972, when the revolution in the south had made significant progress and victory was foreseeable, the Government allowed the Vietnam News Agency to recruit students at universities in the north, especially the University of Hanoi, to become reporters to support the Liberation Press Agency and the southern battlefields,” he said.

“The University of Hanoi at that time had seven departments – maths, physics, chemistry, biology, literature, history, and geography – and their students were all recruited. So were students from the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam and the University of Languages & International Studies.

“That was July 1972. That was why I studied physics but worked in journalism.”

|

| No Title |

The 149 students-turned-war correspondents attended a training course on reporting from July 1972 to January 1973 in Hà Nội, then moved to work in central and southern localities from March 1973 until the country gained freedom in 1975.

For Tích, wartime blurred the boundary between life and death.

“Journalism is one of the dangerous occupations. And being a war correspondent is undoubtedly dangerous,” he said.

“It was normal for us to have everyone going to overthrow an enemy’s station, but carrying the dead bodies of our colleagues back when the fight was over. Simple as that.

“We used to wish each other luck at dinner before going into battle, and lost colleagues on the same night. It was unpredictable. Unforeseeable.”

And because of those sacrifices, the title feels to him like a bittersweet achievement.

“I was happy, so happy to hear we got it because I contributed a little to it. It’s little, but I did contribute,” he said.

“But it’s also sad because the people that deserve to know we got it are no longer alive. That just keeps tugging at my heartstrings.”

Now that freedom has been established and Việt Nam has entered a new era of development, the former war correspondents said it’s important young journalists keep the spirit of the wartime generation.

“Don’t be pessimistic about the negativities you see, and always remember Việt Nam is worth being proud of,” Tích said.

“Our generation was born and raised in the war, so to us, this peacetime is so precious.

“And for the young generation, you always have to think for the country. When you report, write, film, or photograph, remember society is diverse, it has the good and the bad, but we must understand the nature of things and be able to see where the truth lies.”

Don’t be so distracted by modern technology you forget the fundamentals of good journalism, Bền said.

“It doesn’t matter what state-of-the-art equipment you have, humans still decide everything. Equipment is just a tool that helps us,” he said. “It can never replace humans. So self-improvement is still important.”

He added: “Nowadays we lay stress on ‘journalistic ethics’, but I don’t think it’s necessary. The mission we carry is bigger than ethics.

“Ethics are what normal people need to have. But what we do is a noble mission. Journalism has always been one of the four pillars of democracy – it’s the fourth estate of mankind."

Timeless advice for aspiring journalists. — VNS