Politics & Law

Politics & Law

|

Linh Đỗ

Almost five decades after the Việt Nam War ended, humanitarian initiatives such as war veteran Chuck Searcy’s Project RENEW are still working to remove unexploded ordnance (UXO) in the central province of Quảng Trị, the most heavily bombed location during the war.

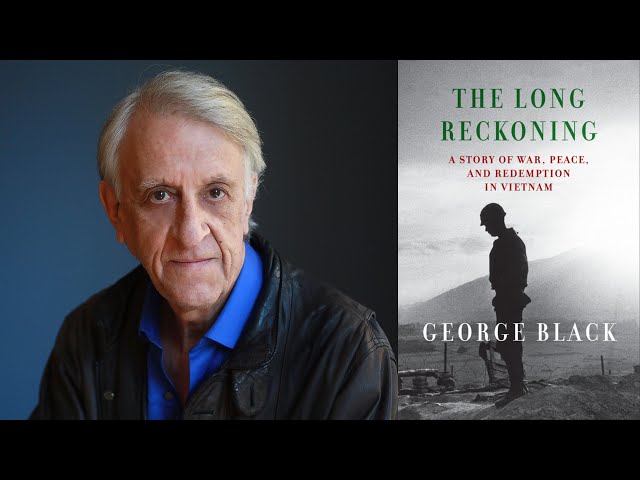

British national and American resident George Black described Quảng Trị as “tiny” in a recent talk in Hà Nội to promote his book, The Long Reckoning: A Story of War, Peace and Redemption in Vietnam.

Despite being 75 times smaller than Germany, the province was subject to more bombing than all of Germany during World War II, about 2 million tons of bombs.

As it was situated in the narrowest part of Việt Nam’s long and thin S shape, right at the 17th parallel which split the country into two following the Geneva Accords in 1954, Quảng Trị witnessed some of the bloodiest fighting between the northern Vietnamese army with its associated National Liberation Front, or Việt Cộng, forces, which pushed inexorably southward and westward along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail on the Trường Sơn Mountain range bordering Cambodia and Laos, and the joint force of the Republic of Việt Nam [Sài Gòn administration] and American forces.

The US forces sprayed 20 million gallons of herbicides and defoliants to deprive Northern forces of forest cover and food crops, and dropped 8 million tons of bombs on Việt Nam, Laos and Cambodia combined, delivering the most intense bombing campaign in military history. Quảng Trị was hit with 750,000 gallons of the toxic chemicals and bombed flat, literally.

As Black recounts in his three-part book, which was published last year by Knopf and covers in roughly equal measure major battles and campaigns, bitter post-1975 relations caused by sore feelings in the US for having lost the war and later international aid, of all the bombs dropped here, about 10 per cent failed to detonate.

By 2014, the Vietnamese government estimated that 40,000 people had died from UXO since 1975, and another 60,000 were left injured. With a population of over half a million, Quảng Trị recorded 3,419 deaths and 5,095 injuries. More than half the accidents were from cluster bombs and M-79 shoulder-fired grenades.

According to Searcy, a former military intelligence officer based in Sài Gòn during the war and one of a handful of Americans portrayed in the book as post-war faithful friends of Việt Nam who have worked hard for years in humanitarian and diplomatic normalisation efforts, what is possible isn’t to get rid of every bomb in Quảng Trị, but reduce the risk to the point where people can go about their daily life without fear of being killed, blinded, or amputated.

The danger remains real, as when the book relates the sudden explosion of a cluster bomb in a rice field in 2016 that took the life of Ngô Thiện Khiết, an experienced team leader at Project RENEW. It was a “cruel anomaly” that occurred after 15 years of advanced demining operations without a single accident.

Compared to UXO, the problem of Agent Orange, the notoriously toxic defoliant sprayed during the war and named after the coloured band painted on its containers, is even more daunting and for many years, remained a forbidden subject that readily threatened to poison diplomatic relations.

According to Black, who writes extensively about international affairs and the environment, of four areas of war consequences that required American acknowledgement and financial support – soldiers missing in action (MIAs), disabled war veterans, UXO and Agent Orange – the last one was the most intractable.

Similar to the supercharged MIA and putative prisoner of war issue in which the US held Việt Nam to unreasonable standards of accountability, even though the American MIA count in Southeast Asia was surprisingly small compared to WWII, and the Vietnamese government fully cooperated and Việt Nam’s own missing soldiers, which were disproportionately higher, the Agent Orange debate reveals an asymmetric power relationship.

In his talk in Hà Nội, Black recalled that as he was writing his book, one thing stood out and made him furious. This was the way four brilliant Vietnamese scientists who first worked on Agent Orange’s health effects, such as children being born with birth defects and young men getting liver cancer, were denounced in the US “as liars, as Communist propagandists, as extortionists who just want to get money of the United States”.

To Black, the treatment of the likes of the late Dr Tôn Thất Tùng, former director of Hà Nội’s Việt Đức Hospital, a world-renowned expert on liver disease who had published on liver cancer and surgery in The Lancet as early as 1963, was simply offensive. It is even worse when one considers that the American veterans affected by Agent Orange themselves also had to fight hard to persuade the US government to acknowledge and compensate them for their illnesses, finally, in 1991.

The Long Reckoning describes in painstaking detail all aspects of the destructive use of such chemical weapons in Việt Nam. Using defoliants to eliminate forest cover was not controversial, but food crop destruction was feared to be a war crime.

As Black told readers in Hà Nội, this second use was pushed very hard by the first president of South Việt Nam, Ngô Đình Diệm. John F. Kennedy opposed it at first but eventually yielded.

Southern authorities initially got permission to spray food crops in only one location, the A Sầu Valley in the then Thừa Thiên Province below Quảng Trị, a key entry point into the South for Northern forces.

Yet, as Black writes, “Once the door was cracked open, there was no turning back.” Most of the South’s 44 provinces, or one-sixth of its land area, ended up being hit by chemicals for both purposes, with a few central provinces approximating one million gallons, and Laos, roughly 600,000 tons, concentrating in a small area along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail. The total number of Vietnamese exposed ranged from 2.1 to 4.8 million.

From this overwhelming scale of destruction, invaluable research projects carried out over the years by Việt Nam's Ministry of Health Committee to Study the Consequences of Chemicals Used in Wartime, Canadian research company Hatfield Consultants and the Ford Foundation have found human exposure and subsequent contamination through the food chain transfer of TCDD, the most toxic dioxin found in Agent Orange, concentrated the highest in former military bases.

Meanwhile, residual dioxin on the surface areas of the forests and fields elsewhere that had been sprayed has mostly disappeared thanks to natural processes after dioxin was exposed to the air. This so-called “hot spot” theory has helped to pinpoint 28 locations that can be realistically cleaned up, such as the A Sầu Valley, Đà Nẵng and Biên Hòa air bases, where the chemicals used to be stored and loaded, and therefore spilt.

It wasn’t until 2019 that dioxin remediation efforts were finally kick-started at Biên Hòa, the “Holy Grail” of all hotspots, because of its sheer scale of contamination, and not purely out of moral and humanitarian concerns.

In recent years, the US has significantly scaled up cooperation with Việt Nam in all fields, including cleaning up its former military bases, as part of an overarching strategy to “pivot to Asia”.

According to Black, if all goes well, the Biên Hòa project will be finished by 2030, six decades after the site was contaminated, with final costs ranging anywhere from US$390 million to $1 billion. Funding will be split between the Vietnamese and American governments, as Biên Hòa retains its military use today and Việt Nam itself has a strategic interest in strengthening it.

As many brave souls who have worked tirelessly to reconcile both sides of the conflict are growing old and retiring, the author quotes Chuck Searcy as saying he feels worried the US hasn’t learned the larger lessons of its war in Southeast Asia. Too often, it seems heedless of John Quincy Adams’s famous injunction, America "goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy.” VNS