Politics & Law

Politics & Law

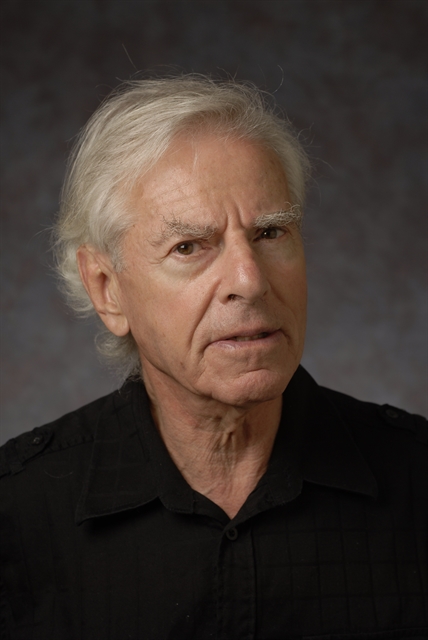

As the 25th anniversary of US-Viet Nam diplomatic ties draws near, Professor H. Bruce Franklin, one of America’s leading historians and the author of many books on the American war in Vietnam like Vietnam War, Vietnam and America and Vietnam & other American Fantasies shared his thoughts about US- Viet Nam relations with Viet Nam News

|

| Professor H. Bruce Franklin |

As the 25th anniversary of US-Viet Nam diplomatic ties draws near, Professor H. Bruce Franklin, one of America’s leading historians and the author of many books on the American war in Vietnam like Vietnam War, Vietnam and America and Vietnam & other American Fantasies shared his thoughts about US- Viet Nam relations with Viet Nam News

On January 27, 1973, the United States formally agreed to end its war in Viet Nam and pledged to “respect the independence, sovereignty, unity, and territorial integrity of Viet Nam.” But it continued to support, arm, and finance military war until the final victory of Viet Nam in April 1975. Then for the next 20 years, it waged economic, political, and psychological war against the Vietnamese nation. Central to that war was the demand that Viet Nam account for thousands of Americans missing in combat, whom many Americans believed were being held by Viet Nam as POWs.

During those two decades, many other Americans were working to end these attacks on Viet Nam and to begin - for the very first time - diplomatic relations between our two nations. In his 1993 essay U.S.-Vietnam Relations: The Past, the Present, and the Future, Professor David W. P. Elliott wrote: “Human rights and democratization may be the next incarnation of the POW/MIA issue, a symptom of an underlying refusal on the part of many Americans to accept the historical verdict of the Vietnam War.” Well, the POW/MIA flags still fly (by state law) in all fifty states and on federal buildings nationwide (by federal law, recently sponsored by a unanimous vote of the US Senate). Professor Elliott’s prediction has also come true. Ever since the beginning of diplomatic relations in 1995, the US has continued to demand and insist that Viet Nam conform to American definitions of human right and democracy. As many tens of millions of Americans take to the streets to protest police terror and ongoing systemic oppression of people of colour, we are hardly in a position to demand that Viet Nam implement the realities of American human rights and democracy.

In 1999, I was one of the dozen scholars of American studies chosen to meet with a dozen Viet Nam scholars of American studies in a conference in Ha Noi. One of the sponsors of the conference was Ambassador Pete Peterson, the first US ambassador to Viet Nam. Peterson, himself a former POW, declared the whole POW/MIA issue was a “hoax". At the conference, an elderly Vietnamese professor asked us Americans if we knew who was the first Vietnamese scholar of American studies. Several of us immediately shouted out “Ho Chi Minh.". This led to a discussion of great relevance today, as we celebrate the 25th anniversary of diplomatic relations between our two nations.

Ho Chi Minh was deeply aware of the central contradictions of American history. On one hand, he knew that our revolution and Declaration of Independence had fed into the French Revolution, next to the Haitian Revolution, and then to the 20th-century liberation struggles of the colonised peoples around the world. But he also knew that our revolutionary nation was a nation built on slavery and genocide. Relying on our professed ideals, Ho Chi Minh wrote his 1919 appeal to the United States on behalf of the people of Viet Nam. He was equally conscious of the dark side of American history, expressed with overwhelming power in his 1924 essays Lynching and The Ku Klux Klan. Despite that, he understood the importance of the bright side of America. I wish every American today could know the opening that Ho Chi Minh wrote for Viet Nam’s Declaration of Independence, September 2, 1945:

“All men are created equal. They are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

This immortal statement was made in the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America in 1776. In a broader sense, this means all the peoples on the earth are equal from birth, all the peoples have a right to live, to be happy and free.

As the great ideals expressed in our own Declaration of Independence are meeting an ominous challenge from those dark forces of our national history, we Americans should stop telling the Vietnamese people how to deal with their problems and instead deal with our own problems as well as problems we are inflicting on the world, including wars on other nations and on the Earth itself. Perhaps we have much to learn from Vietnamese people, including, first of all, how to respond to the global pandemic threatening us all.

It is yet to be determined whether Homo sapiens will prove to be a successful species. The big test is whether or not we can recognise, and act upon, our common humanity. If Viet Nam and America can act as true friends, we can set an invaluable lesson for the world. VNS