Op-Ed

Op-Ed

This is the time that needs active role of trade union and labour organisations in supervising overtime violations in order to protect employee’s rights. Hopefully the more independent organisations truly represent employee’s rights, the better supervising role of these associations will take effect.

|

| Workers at the Global DHA textile company in Hà Tây Province. — VNS Photo Đoàn Tùng |

Khánh Dương

An unpalatable fact about working overtime in Việt Nam was revealed in a survey conducted by Institute for Workers and Trade Unions not long ago.

Vietnamese textile labourers work on average 47 to 60 extra hours per month, far exceeding the 30 overtime hours regulated in law. Looking to the calendar year, the overtime shifts one has to do each year might reach up to 500, even 600 hours.

But the wages revealed in the survey were a bigger disappointment. Average overtime pay for every labourer is estimated at not higher than VNĐ1.34 million (US$58) per month. This accounts for only 22.4 per cent of their total monthly income.

According to the current Labour Code which came into force in 2012, the number of overtime hours must not exceed 50 per cent of normal working hours in a day. A work week is 48 hours, plus 200 hours of overtime a year, and 300 under special circumstances.

The current payment for 200 hours overtime on weekdays stands at 150 per cent of normal payment, 200 per cent for 201-300 hours overtime and 250 per cent for 301-400 hours of overtime. 300 per cent of normal payment I set for those working overtime 500 hours or more.

Some 97 per cent of employers in the institute’s survey expressed their willingness to increase extra time. Employers of textile, fishery product, food processing and electronic sectors have the highest demand for more overtime due to high volume of orders.

One of the noted changes the Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA) has proposed in the Labour Code revision, which is open for public feedback this month, is to increase overtime working hour limits to a maximum of 400 against the current 300.

The change was made following recommendations of enterprises including the Việt Nam textile association and associations of business of Japan and South Korea to meet their demands to increase productivity and use their workforce more flexibly.

Another goal of the proposed change, according to MOLISA’s Labour Safety Department, is to increase Vietnamese employees’ competitiveness. More importantly, working overtime is a desire of employees, majority of whom are migrant workers and shoulder the burden of renting rooms and other domestic expenses.

Deputy chairman of Việt Nam General Confederation of Labour Mai Đức Chính said most labourers are willing to do extra hours to increase their income, as the current minimum can cover only 92 per cent of their daily expenses.

85 per cent of employees asked in a survey conducted in July this year by the confederation said they wanted to work overtime. Workers in big cities with more financial burdens wish to work the most.

Associate Professor Vũ Quang Thọ, an employment expert, said working overtime is a legitimate demand of employees in the context of low payment, but he can’t forget the desperate status of employees he interviewed.

The survey of the Institute for Workers and Trade Unions showed 33 per cent of interviewees with low income struggle to make ends meet. Another 12 per cent said their wages are not enough to survive.

“Employees have no other choice rather than working overtime to increase their income, especially in remote areas,” Thọ said in a discussion on Vietnam Television recently.

Employees said they were willing to do extra time. For many, it is their only choice.

|

| Source: Talentnet Corporation, December 2016. |

Not boosting productivity

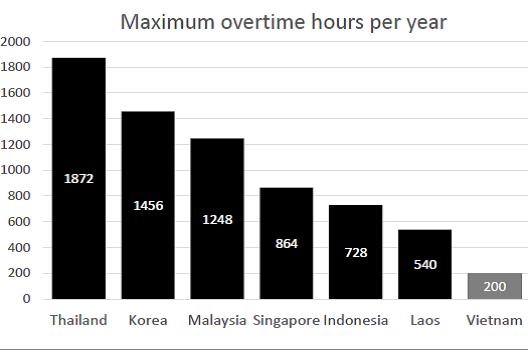

Compared with other countries in the region, Việt Nam’s montly overtime cap remains low, which is part of why employers proposed increasing it.

The maximum overtime hours allowed in a month of Laos is 45, Indonesia 56, Singapore 72 and Malaysia 104. Cambodia and the Philippines don’t even set a limit.

The International Labour Organisation assessed total normal working hours plus extra time of Việt Nam (if a maximum level of 400 overtime hours is approved) could reach 2,720 hours per year.

Although Indonesia’s overtime hours are capped at 728, nearly double the proposed level of Việt Nam, employees of this country work only 40 hours per week. The country’s early maximum normal and extra working hours stand at 2,608 hours, 12 hours less than Việt Nam.

The figure is 2,446 hours per year for South Korea and 2,288 hours per year for China. Calculating this way, Vietnamese workers have to take longer maximum hours than developed countries in the region. Meanwhile, productivity remains humble compared with neighbouring countries.

More working hours does not result in better productivity, with the key issues work quality and the employee’s health.

I am worried about the possible health effects of working too much overtime and non-stop on Vietnamese labourers.

What is the point of working when employees get exhausted after working and spend their money buying medicine?

A worker has to spend 12, even up to 16 hours a day at the factory. Let’s count how much time they have left to take care of their family, clean themselves and sleep.

Working too much results in some problems more serious than exhaustion. In Japan, the word karoshi refers to death by overwork.

Overtime is viewed as a sign of dedication at many Japanese firms. A Japanese government survey showed that more than one in five companies have employees whose tendency to overwork puts them at serious risks of dying. The number of deaths due to overworking in the country has risen so high that the Government has limited monthly overtime and fined companies that do not comply.

At many firms in Việt Nam, labour experts have seen employers forcing workers to take overtime. Per the law, overtime must be implemented based on voluntary negotiations from the two sides. However, employees’ lack of awareness of their rights results in exploitation.

As Việt Nam is about to welcome a series of trade agreements, including the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and European-Việt Nam Free Trade Agreement, employees have the right to establish organisations that represent labourers at companies, besides trade unions.

This change requires an active role from trade unions and labour organisations in supervising overtime violations to protect employee’s rights. Hopefully the more independent organisations that truly represent employee’s rights, the better these associations will be able to supervise. — VNS