A short story by Lê Minh Khuê

|

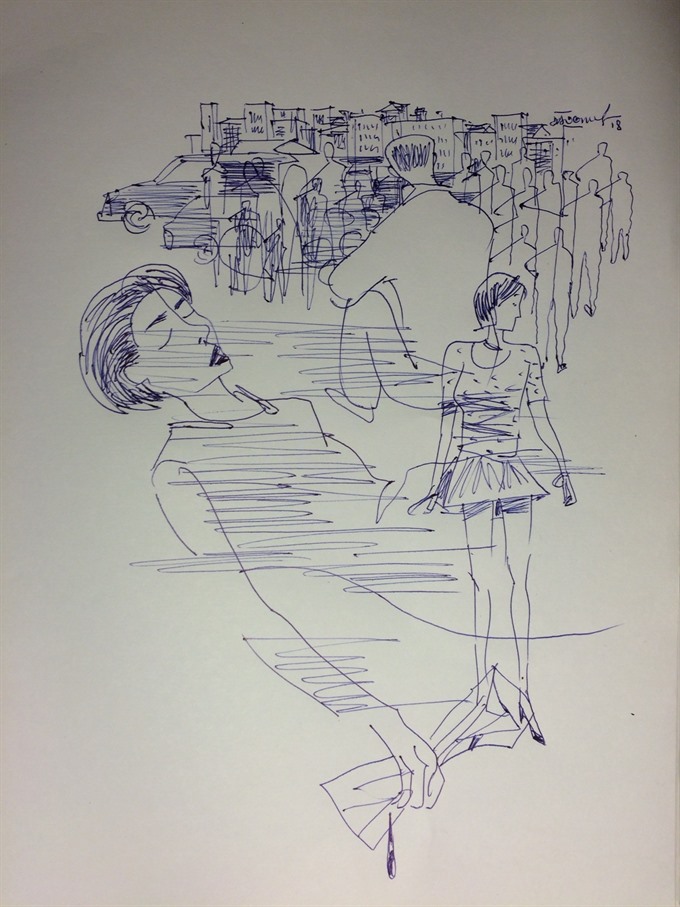

| Illustration by Đào Quốc Huy |

“So your aunt and I will be gone for a few weeks. You’ll take care of the shop. In the evening Vân will be home and review the day’s trade. Don’t worry about business. You’re better off here anyway, because you don’t have anything else to do while waiting for a job offer other than wandering around inhaling traffic smoke or sitting at cafes ogling unemployed girls in short skirts and high heels. It wouldn’t be fun. You’d better look after the shop for us, or else we’ll have to close it and lose customers. Look, we can’t let customers walk away. Is there any house on the street in this whole city that isn’t used as a shop? We have to sell things. Everything. This big market which is our city is perhaps one of a kind in the world. In other cities people set aside a little land for gardens and lawns and green trees. They sell things in separate zones. But here we’re filled with shops. Which is very convenient. You can just run out to the entrance of your alley to buy a box of matches, or to the other side of the street for a motorbike. Okay, I’ll stop rambling now. But hey, your precocious face looks so pathetic. Why don’t you live carefreely like your forefathers who went to war with full belief which made everything as light as a feather? Let me explain more to you about the need to keep the shop open every day. If we were closed for even one day, people would find it strange and peek through the door to see if there is anything wrong. So you must help your aunt and me. Our water filters are mostly fake Chinese products. Customers in the know would just pout and walk away, so we can only catch naïve ones once in a while. They buy our filters and are glad if they work; otherwise, they reluctantly come back for maintenance. At any rate, every shop is fully prepared for warranty maintenance. We just need to offer them a new cartridge. If they want to test the water for toxic metals, they would have to wait for eternity for the test result. They wouldn’t want to waste their time that way. The only reason I’m still selling water filters is because I’m waiting for somebody to rent our shop. As for your aunt and me, we’re tired and our backs hurt from working. And when we lie down in our coffins, nobody will offer us real dollar bills to carry to our afterlife. Just lots of fake dollars. Full bags of them…”

“Okay you can stop now,” Nghĩa’s aunt intervened to cut off her husband’s rant. “The boy has already agreed to help. At your age, if you talk too much, you’ll go nuts.”

Nghĩa’s uncle was 1.55 m tall, and his aunt was 1.62 m tall. The couple had sailed through more than twenty years together without so much as a ripple in their peaceful pond of marriage. He had the habit of talking too much too loud like a ward loudspeaker while she spoke little but tended to describe things astutely and humourously like Hồ Xuân Hương herself*.

Yet Nghĩa didn’t laugh. The 23-year-old boy had a beard and the quiet eyes of a sailor who was thrashed about by waves and storms in remote uncharted seas. He looked at his aunt and her husband, waited for the latter to finish his speech then said “You two can go!”

Nghĩa’s uncle and aunt went away. They took the train to the central region to visit their oldest son whom they had disowned after he dared to marry a woman from so far away. The grandson, who was two now, was prompted by his mother to call his grandparents on the phone, “Grandpa, grandma, it’s little Tý saying hello!” The grandfather coughed and the grandmother teared up. How could they resist?

After Nghĩa’s aunt and uncle left, his cousin Vân hardly came home from work but went to her boyfriend’s house, a pottery shop in the Old Quarter. Vân called Nghĩa’s phone, “Is it you, cousin? However much money you make, you can use it to buy whatever you want. My parents won’t care!” Okay, Nghĩa sighed.

Nghĩa saw a newsstand on the opposite side of the street. He ran through the deadly traffic filled with reckless and seemingly blind drivers, climbed over the road barrier and crossed the oncoming traffic. The motorbikes were driven by guys who treated life like trash, who wouldn’t mind racing from here right to hell to have a beer with Satan, who must be bored of receiving so many dead drivers. Nghĩa fought just to find his way to buy a few sport newspapers. Arsenal were sliding downhill. His favourite football team had suffered defeat continuously, which only served to strengthen his determination to love the team that seemed not to care about fame or money or winning cups at any cost. Arsenal only cared about serving a dreamlike style which was as romantic as love. To play beautifully without violence seemed to be scorned in an age when players cheated and betrayed and stole on the field under billions of watchful but powerless eyes.

Nghĩa had been wasting his youth by thinking. He knew he couldn’t blend in with society. Everyday his parents preached to him and advised him.He sat idly in the shop all day and felt thankful that no customer dropped in. In such heat, even country bumpkins who raked in money by selling pigs and rice would hesitate to go out. As for urban citizens, they would only buy authentic brand-name filters. If they couldn’t, they would rather drink and die from dirty water than from doubt.

This crossroads was the busiest and most suffocating in the city. The worst time was rush hours on summer days. Motorbike gangs who would race to death got stuck into the melting asphalt road. As Nghĩa fumbled his way to the newsstand, the girl seller eyed him as though he were an alien. “Why are you so nervous?” she asked.

“I’m scared of crossing the street!” Nghĩa answered.

“What is so scary about crossing the street? I walk through the crossroads over there to get to school every day. Why did you keep looking around?”

“I didn’t want to get hit!”

“Don’t look. Don’t give way. Even if you look and give way, nobody cares and does the same for you. Learn from me. I just walk ahead without looking at anybody. It works. Just try it.”“I’m not too scared actually,” Nghĩa replied. “I just hate trouble. I like to sit alone in my own corner. But I need to read sport newspapers everyday. Blue-printed and red-printed. I can read dozens of sport newspapers even if they cover the same content. And you run the only newsstand in the whole street.”

The girl laughed slyly. “You’re right,” she said. “It’s foolish to run a newsstand here. Nobody reads anything. We’re running our shop only because my grandpa feels bored. He said in the old days, people had to wait in line with their permits just to buy newspapers and books. My grandpa misses the old days. Look at him.”

Inside, an old white-haired man wearing silk was watering a table plant. He looked like an antique. He didn’t care about all the grotesque noises crashing in from outside. Nghĩa nodded and thought the old man was exactly like his granddaughter. The old man could also cross the street nonchalantly. The girl felt Nghĩa’s sympathy for her grandfather. She tugged at Nghĩa’s arm as Nghĩa was looking like an old man, terrified by streets. She wanted to help. “Don’t worry,” she said. “I stay at school all day but in the afternoon when I go home, I’ll bring you newspapers.”

Nghĩa looked dazed. His face looked all the older with the growing beard that he hadn’t shaved for days. The girl burst out laughing. “Are you afraid of falling behind the news?” she asked. “You can read newspapers in the afternoon, right? Reading old news is even more interesting. There is a guy over there on the other side of the street who loves reading old news. He says up-to-date news scares him. He has to take time reading. Old news calms him down. Isn’t he funny?”

Nghĩa didn’t laugh. The girl extended her hand to him. “Let’s make a deal. I’m little Chíp. It’s my nickname at home. My full name is very complicated. Nguyễn Lê Vũ Thước Minh Hương. Sounds so scary and boring. Horror movies are more interesting.”

Nghĩa sat on a plastic chair looking at the crossroads which was congested in the afternoon. Seen from all four directions, the traffic looked super-jammed and pitch-black. The black lines stretched for several miles. The asphalt road absorbed and emitted heat like a gigantic gas stove. Heat steamed up in torrents from the air. Women hid themselves completely behind sunglasses and masks and arm-length gloves.

Nghĩa jested, “Where in the world can women display their beauty now?” Little Chíp used a hand to hide her mouth which was smiling and baring a wide tooth gap. “In the kitchen,” she answered. “In the air-conditioned office like my mom’s workplace. In the café in the afternoon. And in the bedroom. Aren’t there plenty of places for that?”

The 14-year-old girl struck Nghĩa as precocious as kids on TV these days. Those kids knew everything. They terrified Nghĩa. Yet somehow little Chíp sounded and looked okay. It seemed about time that she knew that women displayed their beauty in the bedroom.

Nghĩa lamented the death of the sight of dandies shyly and nervously following beauties these days. Little Chíp commented, “Aren’t people too busy for that? Look at my mom. Every day when she goes home, I’ve already gone to bed. My mom and dad have such a funny relationship. Every week dad visits mom, grandpa and me for two days. Sometimes at the beginning of the week, sometimes on weekends.”

“Why?” Nghĩa inquired. “I don’t know,” little Chíp said. “Dad is busy with business and so is mom. They say it saves time when they live separately in their own houses. They’re free to do whatever they want.”

“Scary. They can’t be in love with each other!”

“Just the opposite. At night they talk incessantly on the phone. Once in a while, dad picks mom up on Sunday evening to go dancing, or to have coffee. I find this arrangement alright. My aunt and uncle live together but fight each other everyday. Mom and dad don’t seem to get bored with each other. Grandpa said what a stupid crazy bunch!”

“I agree,” Nghĩa said. “How can a husband and wife live separately? Even Westerners don’t live like that.”

“What an old man you are,” little Chíp said, looking up and down at the quiet guy. “You’re as old as grandpa.”

Every afternoon without fail, little Chíp brought newspapers to Nghĩa. Nghĩa felt relieved whenever there was a traffic jam. In a traffic jam everything stood still. The girl only needed to worm her way through. It was smooth traffic that was terrifying. Nobody heeded anybody. Everybody tried to race forward. Anybody who could be a few inches ahead would be considered the great winner.

Bobbing faraway on the other side of the street was little Chíp’s short hair. Her hair was as thick as tree roots. She had to use a big headband to keep it in order. Her forehead looked square and protruded forward, and coupled with her square chin, gave her face a square look. She looked both cute and naïve like a baby who was sucking milk. Yet her head was full of seasoned thoughts.“Why do you read sport news?” she asked Nghĩa one day. “I don’t. Even football is dirty now. Scary. I’d rather watch scary movies!”

Nghĩa burst out laughing at little Chíp’s way of speaking. The two often talked to each other. On one congested suffocating afternoon, little Chíp pointed to a car and lectured, “Look here. It’s a Murano which costs almost 2 billion dong. As for the car over there, it’s a Lexus GX 470, with a stylised L as its logo. Toyota produces this line exclusively for the American market. It’s a powerful all-wheel drive with eight seats and a 4.6 l engine. It’s 2.5 billion dong.”

“God. Where do you learn all this?” Nghĩa exclaimed.

Little Chíp smiled broadly, squinting her eyes. “My dad sells cars,” she said. “Dad teaches me carefully. I remember everything.”

Nghĩa learned to observe cars by following little Chíp’s instruction. He could identify cars of almost 3 billion dong which got stuck amid rolling flows of motorbikes. Owners of Muranos and Hummers sat secure and hidden patiently waiting for the road to clear while the inferior bikes around them were staining their cars with smoke. As rich as they were, they had to wait too.

Rich people in this country suffered after all. There was a phở shop near Nghĩa’s house in the Old Quarter. Upper-class phở addicts drove their cars there. The luxurious elegance of the latest Mercedeses seemed to ignite the secret classism of the Old Quarter. Yet the ladies and gentlemen, the modern day upper class couldn’t find any place to park their cars. They might spend a whole morning looking for parking spots without being able to eat a bowl of phở. But they were patient. They could wait to park and set their precious million-dong shoes on the sidewalk and walked leisurely in their gowns and suits which exasperated everybody else but which was nothing to them because as the new aristocrats, they knew they must persevere amid the mud and dust.

Even wealthy owners of billion-dong cars wasted their time getting stuck in afternoon congestion without being able to do anything about it. There wasn’t a separate lane for the rich. Their cars shared the same fate with bikes. For their parts, high-power scooters or ‘super’ scooters over 250 cc from Honda and Yamaha also had to stay put on the jammed road with Chinese bikes and Honda cubs of the 1970s.

Little Chíp pointed toward a ridiculously pompous and posh bike. “Look over there. It’s called the black rhino. My dad has bought one.”

“Scary,” Nghĩa said. “I can’t imagine myself riding such a big bike in this city.”

Little Chíp looked at Nghĩa strangely. She raised her hand to rub the boy’s beard like a naughty younger sister. “So what do you like best?” she asked.

“I like green pastures and big old trees and well-trodden paths,” Nghĩa replied. “In the distance we can see houses. I like a house nestling in a forest. I would cycle to the city to work then cycle back home and rest my bike by the fence. In the kitchen my mom is cooking and my dad is playing chess. I walk into the back garden to play basketball with little Chíp then inhale the crystal clear and fresh air…”

Little Chíp laughed ecstatically like a drunk boy. “You’re a dreamer,” she said. “Where in the world can we find big trees and green grass for you? But there’s plenty of vehicle smoke and road dust which is thickening day by day so you can’t escape even in your dream!”

The owner of the clothes shop next to the water filter shop sat idly smoking and listening to the boy and girl chatting with his hands in his shorts’ pockets in just another congested afternoon at the crossroads. He told little Chíp, “I know you’re the granddaughter of the old newsstand owner over there. Your grandfather is funny. His son-in-law makes billions selling cars and his daughter rakes in that much working in banking, but he still chooses to toil away at his newsstand.”

Little Chíp didn’t reply. She looked at the guy as if he were a strange object. The guy spoke just like everybody else. Everybody thought her grandfather was greedy. But she knew that her grandfather only worked because he didn’t want to be idle. He often gave away all of his money. He still had many destitute relatives in the countryside to care for.

Noticing little Chíp’s simmering anger, Nghĩa asked the guy to cool the situation, “How is business?” “As you’ve been sitting here for a few days, have you seen anybody come here to buy clothes?” the guy retorted. “It’s damned hot. And my whore at home only buys outdated styles. Young girls walk by, take a glance, then walk away. What a bore!”

“Your tank tops over there seem fashionable to me,” Nghĩa said. “Nah,” the guy said. “It’s fashionable today then runs out of fashion tomorrow. Fashion runs in a tiring circle. I’ve seen on Discovery a bunch of native men living somewhere in the Pacific. They’re the most fashionable to me. They hide their penises in ivory-like tubes and carry along a few other tubes for backup. Their whole bodies are naked except their penises. I dare any fashion designer to display such a style. I bet that unique style would take Paris by storm.”

Nghĩa turned around in an attempt to protect little Chíp from hearing such straight talk. But little Chíp remained unflinching. She was an experienced street crosser after all.

Little Chíp had a summer break. She told Nghĩa that she could bring new newspapers to him at any time in the day. At noon Nghĩa often sat quietly looking out at the street. The suffocating heat made the air before his eyes appear blurred and watery. He felt dizzy. The road at high noon. It seemed as if the devil were standing guard in the air. Upon reaching an ad sign, a motorbike suddenly fell to the ground. The rider crawled back to his feet, picked up his bike and looked around to see who the culprit was. As there was nobody in sight, the guy climbed back on his bike petulantly and rode away. Half an hour later, two youths riding a bike also fell down at the same spot. They also picked up their bike, cursed between their teeth, then rode away. In exactly half an hour later, a woman riding a bike with two baskets of eggs also fell down. From noon until afternoon, with surprise Nghĩa counted as many as seven bikes suddenly falling down on the spot. “There’s nothing strange,” the clothes shop owner said. “The road is like the river which can claim human sacrifices. The spot may lie on top of a graveyard. My eyes have grown tired seeing people falling down there for the past few years. The devil is playing a joke. He’s just teasing, nothing serious.”

In the summer little Chíp didn’t cross the street in the afternoon. She crossed it whenever she could, to have a chat with Nghĩa. One afternoon at three, when the road was empty and a few motorbikes were racing away insanely, little Chíp stood on the other side of the street waving a newspaper. Before Nghĩa had time to stop her, the girl plunged out. Her hair was dyed bright red. Her T-shirt was also red and the sport newspaper she was carrying was also printed in red.She walked across the dangerous spot. Nghĩa’s face darkened when he heard a loud crashing sound. A motorbike carrying two boys about little Chíp’s age crashed into the sidewalk as it tried to avoid the girl. The boys were flung against a tree.

A Honda Silver Wing shot toward little Chíp. More earthshaking sounds ensued. Residents nearby poured out.

Nghĩa didn’t dare to look at the ambulance carrying little Chíp away along with her red sandals and newspaper which she was clutching tightly in one hand. Her hair fell on the road. Nghĩa picked it up and carried it back to his shop.

God please don’t let her die. Please God. I’ve told you once but you didn’t listen. How can you cross the street alone. VNS

*Hồ Xuân Hương (1772–1822) was a Vietnamese poet who lived in an era of political and social turmoil between the Lê and Nguyễn dynasties. Writing in the local Nôm script, she is considered one of Viet Nam’s greatest classical poets.

Translated by Linh Đỗ

.jpg)