A short story by Phạm Thị Thúy Quỳnh

|

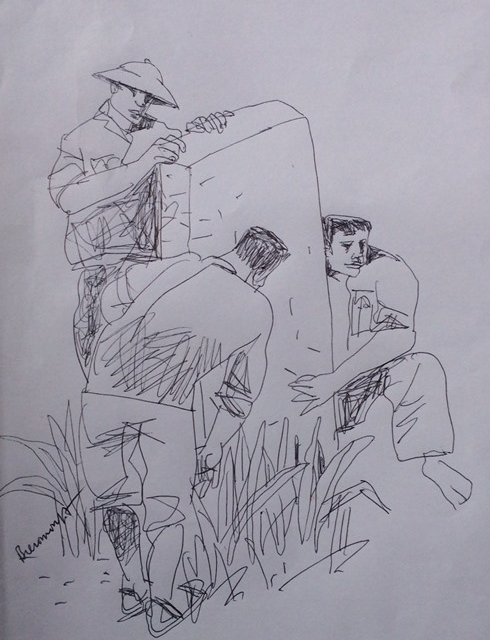

| Illustration by Đào Quốc Huy |

by Phạm Thị Thúy Quỳnh

It was a summer afternoon.

Plants and grass withered in the scorching heat. So did two large alocasia leaves over the baskets of dung which lay heavy on the pole on my sore shoulders. My sweat trickled down my eyes. When I walked across the rice fields then the bamboo bridge spanning the small river, I felt uneasy because one of my turned-up trouser legs came loose. “Let it be! Anyhow, I’m nearly at the cottage,” I said to myself.

* * *

I was not a resident of this locality. My native village was Nhồi, famous for its stonemasonry. In my late teens, I got a university degree before becoming a reporter for a provincial newspaper. A few years later, tired of being an underpaid and under-appreciated journalist, I returned home to be a sculptor. The villagers sarcastically referred to me as the local intellectual.

“What’s the use of your father’s knowledge? Can it provide us what we need to live?” my wife once told our little son jokingly. “You see, only rice is important, my beloved child,” she added.

I joined a group of freelance craftsmen in Nhồi Village who had been hired by the local authorities to transfer the half-ruined stela in memory of King Lê Lợi to a faraway northern area to make room for the Hoà Bình hydro-electric power project.

Before my leaving, my lovely wife prepared sticky rice as my food for the planned journey.

* * *

“Lý, you’re taking dung home to fertilise the kitchen garden, aren’t you?” asked Miss Phồng residing in Thượng Hamlet.

Her father was also from Nhồi Village. After travelling across the country he settled down in Hoà Bình Province. It was there he married a pretty young girl, Phồng’s mother, and made up his mind to live there for good.

In my heart of hearts, I often hoped that some day I might meet him, my kind-hearted co-villager in this strange land.

“Yes indeed! Our landlord gave us workers a small plot of land to grow vegetables on during our stay here. Where are you going in this hot weather?”

“My dad’s just told me to offer you workers some fish. Luckily for me, I saw you on my way over,” she answered.

“Please, tell him thank you from me. How kind of him, treating us like his own children!”

“Dad told me that you’re here to help us villagers improve and move the stone stela before this area turns into a reservoir, a noble task,” she went on.

“He’s too kind. We’re just doing our jobs,” I replied.

“I must be going to Thượng Hamlet now. You should go home for a rest before going on with your task,” she said.

“Where are you going now?” I asked her.

“Mr Ninh’s place to give him some medicinal herbs, another task from my father.”

“You’d better leave now. It’s already late afternoon,” I reminded her.

“Before I forget, Dad invited you to come to our place for dinner tomorrow evening to thank you for lending him the The Romance of the Three Kingdoms.”

Her remarks about that great Chinese epic brought me back to the days I had first moved here with many famous novels from China and Russia. Mr Tham was very interested in my small treasure of foreign literature. He asked me to lend him that historical work of ancient China.

Our group of stone workers was composed of twenty craftsmen; most of us were Nhồi villagers, while the rest came from Ninh Bình Province. Our dwelling was merely a long thatched cottage temporarily rigged up by a local fisherman. After nearly half a month we had been able to finish most of the work, which had been more complicated than we had imagined.

I walked into the long house. Everyone was sleeping, except for Lĩnh, one of my fellow villagers, who was still wide awake. He was two years older than me. He was so skilled that his products sold like hot cakes. Now he was making a wooden lion.

“Your food is in the tray on the mat over there,” he told me.

“Oh yes, I see, I see! Thanks a lot, pal.”

Before eating, I took The Tale of Kiều, the masterpiece by poet Nguyễn Du, the greatest figure of ancient Vietnamese literature, lent to me by Mr Tham, to enjoy. Reading at night was one of my few habits remaining from my time working as a lowly scribe in that lowest of professions; journalism.

* * *

I went to Miss Phồng’s place to give back the book to her father. Unluckily, he was out. At once, I returned to my place across a vast rice field close to the bridge. Nearby lay many big holes for straw manure or as feeding storage for cattle. During the night, the road was deserted and the whole area was covered with a yellow moonlight. Suddenly, I heard the sound of footsteps in the water. “They’re probably kids pulling up their small fishing nets out of the river,” I said to myself.

* * *

On the opposite bank stood our unfinished stele. Accidentally, I vomited up what I had previously eaten. I walked slowly and steadily to the river to rinse the bitter taste out of my mouth.

I looked up. Nobody could be seen around. While I was watching the waves going up and down because of the night wind, I heard an ear-splitting shriek. “It sounds like a little girl,” I said to myself. I slowly walked towards a big straw pile where I thought it had come from. With my knife in hand, I moved forward inch by inch. Then the cry stopped abruptly. A slim figure suddenly appeared in front of me.

“Who’s that?” I asked.

An elderly man stared at me when I approached him.

“Oh dear, Mr Tham! What are you doing here at the wee hours?”

He seemed bewildered for a few minutes, then a small, twisted smile crept across his face.

“Dear me, Lý! I’ve dropped the fountain pen you gave me some days ago. It must be somewhere around here.”

“Well, my dear man, don’t worry. I’ll get you a new one. You’ll catch a cold if you stay out here any longer!”

“Of course! How silly I am!”

“Did you hear any weird sounds a few minutes ago?”

“Oh no no! Not at all.”

“I thought I heard the cries of a little girl.”

“There are a lot of kids around here. Maybe it’s Mrs Phước’s young daughter. When she shouts aloud, villagers of both Thượng and Hạ hamlets can hear her clearly.”

“I might be wrong. Anyway, let’s get you home and tucked into bed,” I told him.

“How kind of you! Maybe I’ll give you my daughter Phồng’s hand in marriage!”

I burst out laughing at his joke and nearly forgot the worries still staying heavy in my heart. After accompanying him to his place, I hurriedly returned to our cottage.

In the dim light of a paraffin lamp I looked for a notebook I had brought with me and started writing.

* * *

A few days later, our work was finished. We had to cross the river by boat to the other bank where sat our newly-improved ancient stele. With our great efforts, finally we managed to carry it to its new position.

While I was crossing the field, I saw a lot of people standing around a huge pile of straw. “They’re talking about something special,” I whispered to myself. To my surprise, I found Mrs Phước wailing uncontrollably.

“What’s the matter with her?” I asked one of the fishermen standing beside me.

“Her 9-year-old daughter passed away a few days ago.”

“Did she drown?” I whispered to myself much to my embarrassment.

The mournful cries of Mrs Phước made me a little confused after Lĩnh told me about the little girl’s tragic death. She had been raped and then strangled to death. After that, her body was hidden in a dung hole covered with straw. It was the terrible smell of the corpse that had laid bare the murder.

That evening, after dinner, I tried to figure out the criminal. I pictured the snowy-white head of Mr Tham, the childlike cry and the decayed body.

I felt sick. Picking up a bowl of medicinal herbs, I took a deep draught of it. Yet, I was unable to get rid of the bitter taste in my mouth.

* * *

Time passed and we were going to return home with our work done. All the preparations for the dam had been made. However, the image of that brutal killing stayed fresh in my heart. Again and again, I reminded myself that I had better forget that heart-rending matter, as it wasn’t my responsibility. But the figure of Mrs Phước going to and fro along the river bank day after day haunted me. Sometimes, at night I dreamt that the soul of the little girl came to me to ask why I had not yet shed light on her fate. Nevertheless, I was afraid that I couldn’t be certain I knew who the killer was. On the other hand, I had no other leads.

That morning, while I was sitting at my desk before writing about life in general and then about Mr Tham in particular, Lĩnh rushed in, puffing and panting.

“Miss Phồng has passed away,” he told me.

“What?” I blurted out.

“While catching fish upstream, she was dragged into a whirlpool. Nobody could save her.”

“Why not?”

“Because she waded waist-deep through mud.”

“When did she die?”

“This morning.”

Putting on my clothes, I went upstream. It took me hours to reach the scene. Her body lay under a sedge mat on a river bank with a pale face. Next to the corpse stood Mr Tham, her father. He stared at the black mass of mud. I sat down beside him. In front of us the current passed idly amid the canopies.

“Do you remember Mrs Phước’s daughter now?” I asked him quietly.

He just stared at me. After that he knelt down beside his daughter’s body, weeping lamentably without answering. I felt quite embarrassed.

I was ashamed of myself. I came to a father who had just lost his daughter to allude to the death of Mrs Phước’s little one with no concrete evidence he was the killer, especially after he had treated us like his own children.

Heaving a sigh, I stood up before leaving. I left aside all my doubts and the misery of this place. Behind me, the deep river slowly and tranquilly flowed down into the ocean.

Translated by Văn Minh