Life & Style

Life & Style

When a person starts to talk about Đặng Nhật Minh’s films, it’s not easy to be brief. Each film opens doors and windows onto many aspects of life, and these lead to still more doors, each revealing more facets and shades and issues about the human experience. In other words, the films have the richness and complexity of life, because they’re made by someone who is experiencing it first hand.

|

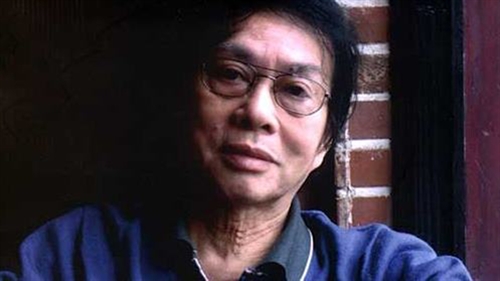

| Seeking compassion: Đặng Nhật Minh leaves no stone unturned to search for humanity even between war enemies. — Photo courtesy of Thể thao văn hóa magazine |

by Dan Hambleton*

When a person starts to talk about Đặng Nhật Minh’s films, it’s not easy to be brief. Each film opens doors and windows onto many aspects of life, and these lead to still more doors, each revealing more facets and shades and issues about the human experience. In other words, the films have the richness and complexity of life, because they’re made by someone who is experiencing it first hand.

Season of Guavas

The true artist communicates universally. The message hits people directly — the communication is clear. That’s why a person’s understanding of the tragedy in Season of Guavas doesn’t depend on that person having lived in Hà Nội, or on having lost their house and had their world disrupted and destroyed forever. It is something all people can understand anywhere in the world. Injustice, outrage, betrayal, greed, corruption of mind, spirit and society — these are things many people have experienced all too often.

The skill of the artist is in presenting these realities and truths in such a way that the viewer, listener, or reader is led along on a journey that takes them to the core of that truth, allowing the viewer to experience something that he might have sensed but has yet to articulate. And that clarity of a truth which the artist, in this case Đặng Nhật Minh, shapes and molds to drive his message home, reaches the recipient’s heart, and it’s there that the viewer’s defenses are disintegrated and he experiences the truth, and its power.

This is the great skill of an artist like Đặng Nhật Minh.

To be such a master of his art requires tools, the tools that those working in any medium need to acquaint themselves with in order to create. But these tools are meaningless in the hands of countless others — often you get effects and shallowness, or even skillful, but empty, technique. But to accomplish what Mr. Minh does requires something much more rare — the intelligence and keen observation of life around him combined with the humility to not set himself above the lowliest of persons he meets, or whose stories he hears. This is constantly evident in his work, where we see characters who in other films would be called “extras”.

In Minh’s films no character, no matter how briefly he or she appears, is unimportant. In fact, one can sense the opposite, that each of these persons is just as important as the characters who carry the weight of the story. A clerk in an office might be talking to a main character about something that seems trivial, and yet a key element in the film might hinge on what that clerk or minor official says. And whether the crucial aspect of the story depends on that character or not, still the scene and that character are related to the main characters in a deeper human way. Minh understands that they are all sharing the experience of life, that life is brief, and that death is the great equaliser of all people. Each one has their own memories and carries their own responsibility.

The medium of film is different in its process than other art forms. In regard to painting, for example, French artist Maurice Denis said that before it is a recognisable scene of a war horse or a woman or the description of some story “[a picture] is essentially a flat surface covered with colours arranged in a particular pattern.” He wasn’t saying that those colours and shapes were the first step to be later refined into a horse, etc. He meant that even after you see the finished picture with its details, it continues to be a flat surface with deliberately arranged colors. What about the medium of film? It doesn’t depend on this kind of juxtaposition, with the different elements presented to the viewer simultaneously on the same surface. Instead it flows in time.

But rarely does a film consist of a single shot flowing in time. Most films are a series of many scenes, camera angles and shots following one another in succession. Exactly what those shots or scenes consist of and how long each one is, largely constitutes the language of film. Mr Minh chooses the order of these shots, each one’s length, and their precise character, that is, the composition of the frame, what is visible in the frame and what isn’t, how close or how far away the characters or objects are from the camera, the specific colors seen and the lightness or darkness of the shot, whether or not characters are speaking or any other sound is heard, whether or not music is present, and very importantly, the relationship of a particular scene to the one immediately preceding it and following it, as well as the scene’s relation to still other scenes much earlier or later in the film.

How to position these scenes and what exactly they will consist of are enormously complex decisions to make. These decisions are what make the movie live and breathe. They embody techniques such as slow or fast pacing, panning, close-ups, contrast, tension, introspection, symbolism, and countless more, and they generate real emotional and psychological effects in the viewers. Mr. Minh’s artistry consists, not only in his creation of the scenes themselves, but in their assemblage in such a way so as to accomplish his purpose, to guide the viewers where he progressively wants to take them.

Season of Guavas, a film from almost fifteen years ago, shows all of the director’s skills at work. It is a tale of modern, peacetime Hà Nội, much as it is now, but set in 2002. And it is a cautionary tale, a message that Đặng Nhật Minh has for his audience. To communicate his message, the director first weaves a tapestry of life. Details of the city take the viewer beyond the surface to show the grittier tenements and narrow alleys, the old stained buildings, the small but tidy rooms, the collective outdoor water facets and latrines, the noisy and bustling street market, the austere art academy class with its students concentrated on their work, the meager offices of police and other government officials, the sparsely furnished hospitals, the sidewalk barbers, the gentle flow of bicycle traffic, and coexisting with this side of life, the wealthier parts of town, the restful tree-shaded avenues, the beautiful old mansions, the villas, the luxury hotels. In short, the viewer is introduced to the real Hà Nội, its essence. Season of Guavas is the most ‘Hanoi’ of films.

At the same time the viewer is introduced to one of the principle characters in the film, Hòa, a 35-year-old man living in the poor side of town. Minh’s cautionary tale centres on this character. The director’s camera lets the viewer see Hà Nội through Hòa’s eyes, taking him into Hòa’s personal world, but giving no hint as to what this modern day parable is about. Minh chooses to not spell out what is going on.

Rather, he lets the viewer gradually figure it out. The viewer likes Hòa. He has an openness and ingenuousness. He smiles when people talk to him, is eager to help, and is always gentle. Simple things give him pleasure. The camera lingers on his face, lit up with joy at the sight of a guava fruit hanging from a tree. The lighting and the colours that the camera captures reflect that joy. Scenes suddenly appear that are from another time, an earlier time and an earlier Hà Nội. Children are playing and reaching for the guava fruit from a large tree near a big house. They’re seen inside the comfortable rooms of the house, playing as all children do, and singing songs with their parents. It is an idyllic, wonderful time, a time of security and warmth and closeness to family members. But these scenes disappear as quickly as they occur.

The viewer is gradually being taken on a journey into Minh’s cautionary tale, and is only by degrees coming to an understanding of the situation. The element of discovery is very important to Minh. It’s only gradually that the viewer realizes that Hoa is mentally challenged. He is not a “normal” person, but has the mind of a 13-year-old boy inside the body of a man. But now it doesn’t matter. Minh has let us come to know Hoa already, and so we don’t care. We love him anyway, and only want the best for him and his younger sister Thủy. The director has masterfully prevented the viewer from forming any prejudgments or preconceived ideas about Hòa. Now the viewer watches with keen interest to see what will happen in Hòa and Thủy’s lives.

The viewer realises that Hòa and his siblings had once lived in the large mansion where Hòa finds the guava fruit. Thirty years earlier, during wartime, their father, a lawyer, had been asked to allow the government to use the house for its offices. However, the house had never been returned to the family and has since been reassigned to others. Now their father is dead, their older brother has moved from the city, and Hòa and Thủy live in a small tenement apartment. Hòa understands nothing of these events, but is only drawn back to his old house with its pleasant memories and large guava tree.

In the course of the story, as Hòa’s “trespassing” gets him arrested, still more scenes of Hà Nội life and people are presented. So many details, in the hands of another director, would descend into “naturalism”, that is, a kind of boring realism that doesn’t go anywhere and distracts from the heart of the story. But in Mr. Minh’s hands, each detail is carefully chosen like the notes in a symphony to add its own colour and propel the story forward. Each detail is like a brick, building the viewer’s understanding of Hòa and his sister’s world, allowing the viewer further into that world with ever increasing empathy.

In this complex but skillful process, Mr. Minh sets the stage for his cautionary tale in such a way as to leave the viewer most vulnerable as to what is to come. The viewer is blindsided and emotionally impacted by what follows, as if it is happening to himself. The events take on a power they would not otherwise have had, and drive home Minh’s unforgettable message. — VNS

* Charles Daniel Hambleton is a US freelance artiste by training based in Hà Nội. He held various jobs to support his artistic career including working as a subcontractor for a vinyl repair business and owner of a commercial window cleaning service. A certified ESL trainer, he has been teaching English at various centres in Hà Nội and also held a painting exhibition in the city’s Old Quarter.

**See the second part of the story: Don’t Burn: an odyssey into the true meaning of life

|

| Through his eyes: "Season of Guavas" explores the depths of recent urban history through the eyes of a never-grown-old man. — File Photo |