Environment

Environment

On March 7, 2017, Viet Nam News published an article titled “Mekong water diplomacy vital”. The article quoted several statements by Dr Lê Anh Tuấn, Deputy Director of the Research Institute for Climate Change at Cần Thơ University.

On March 7, 2017, Viet Nam News published an article titled “Mekong water diplomacy vital”. The article quoted several statements by Dr Lê Anh Tuấn, Deputy Director of the Research Institute for Climate Change at Cần Thơ University.

The Mekong River Commission (MRC) Secretariat takes this opportunity to respond to some of the statements in the article and highlight where water diplomacy is influencing outcomes.

“The construction of many hydro-electric power plants on the river has resulted in scarcity of fresh water in the lower Mekong Delta”

The above statement was made in response to the drought in 2016, which was considered a meteorological drought year.

Construction of hydropower plants on the river does not necessarily result in the scarcity of fresh water in the lower Mekong Delta, particularly during the dry season. Conversely, hydropower plants can contribute to increased flow during the dry season as they discharge water for energy production, contributing to increased flow in the river channel. However, the flow may reduce during the wet season as the dams store surplus water.

Two information sources indicate increases in dry-season flows due to operation of dams.

1.1 Lancang emergency release flows ease drought conditions

In the upper Mekong basin, known as the Lancang in China, the 2016 drought event resulted in 16 per cent less flows compared to the long term average. As such, this would ordinarily translate to lower flows in the lower Mekong basin in 2016. However, because of the water stored in dams in China, emergency water releases from these dams increased dry season flows to mitigate the effects of the drought.

For instance, despite the drought conditions during the months of March – April 2016, flows in the Mekong were higher than average flows over the period 1960 – 2015. This is directly because of emergency water supplements from cascade dams from China.

A total of 12.65 billion cubic meters of water was discharged from Jinghong hydropower reservoir over the period March to May 2016. These releases amounted to between 40 – 89 per cent of flows along various sections of the Mekong river. The emergency water supplement increased water levels or discharge along the Mekong mainstream to an overall extent of 0.18-1.53m or 602-1,010m3/s.

If these emergency releases would not have happened, flows would have been 47per cent lower at Jinghong, 44 per cent lower at Chiang Saen, 38 per cent lower at Nong Khai and 22% lower at Stung Treng. This additional flow has also alleviated salinity intrusion in the Mekong Delta.

A more detailed description of the emergency operations is provided in the Joint Observation and Evaluation Technical Report produced between the Mekong River Commission and the Chinese Ministry of Water Resources. The report is available at: https://www.mrcmekong.org/assets/Publications/Final-Report-of-JOE.pdf.

1.2 Trends on flow over period 1960 - 2013

At present, storage dams on the mainstream are only in the Lancang portion of the Basin. None of the Laos mainstream dams are fully constructed so are not impeding flows, and are not true storage dams (they are classified as run-of-river dams).

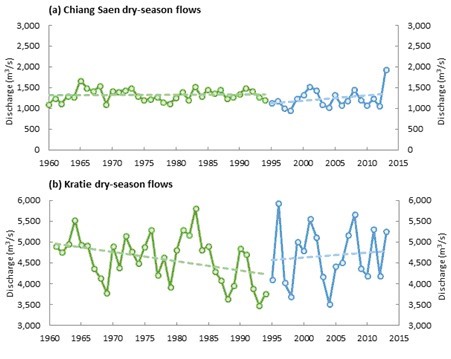

Since 1995, with dam development including the more recent construction of the Lancang dams, there has been an upward trend in dry-season flows. This is shown in the figure below which shows flows monitored in the northern part of the Basin at Chiang Saen gauge in Laos near the Chinese / Myanmar border, and also at Kratie gauge in Southern Cambodia in the Southern part of the Basin.

Flows at Chiang Saen show a moderate upward trend in dry season flows. This is attributable to increased dry season releases directly from Lancang dams. We see an even greater upward trend in dry-season flows at Kratie which is presumed to be primarily a result of dam releases from tributary dams in the Lower Mekong.

|

| Figure: Trends of annual dry season flows at (a) Chiang Saen and (b) at Kratie for 1960-2013 |

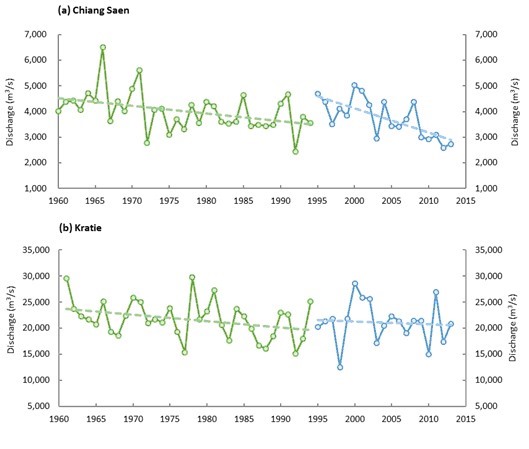

Conversely, in the figure below, we see a clear downward trend in wet season flows at Chiang Saen, and less pronounced at Kratie, which is likely to be a result of dam operators storing water in wet seasons and possibly an increase in extractions of wet season flows for productive purposes.

|

| Figure: Trends of annual wet season flows at (a) Chiang Saen and (b) at Kratie for 1960-2013 |

“The reduction of alluvial soil at hydro dams has also had negative impacts on the quality of the fresh water at the lower end.”

Hydropower dams may have the potential to trap sediment in the reservoir and thereby may cause some adverse effects. However, through the MRC PNPCA (Procedure for Notification, Prior Consultation, and Agreement) process, a thorough review of dam design and functionality is considered.

Through this process, we have seen, for example, developers of the Xayaburi dam modify the design to improve movement of silt and facilitate the migration of fish.

“Việt Nam must also pursue diplomatic measures with countries in the upper regions of the Mekong Delta in order to ensure the equal sharing of water benefits”

Viet Nam is a signatory to the 1995 Mekong River Agreement and has ministerial level representation on the Council and head of department level representation on the Joint Committee. Further representation is also provided through government officials within various committees and expert groups that work with the MRC Secretariat.

The MRC website provides further information on the governance and organisational structure of the Mekong River Commission showing where representation occurs.

“In addition, it is imperative to develop different scenarios or projects on climate change with neighbouring countries.”

Over the last five years, Mekong partner countries have participated in the MRC Climate Change and Adaptation initiative (CCAI) which was a direct response to the member states’ call for a collaborative regional adaptation initiative to climate change and its challenges.

Climate change adaptation is one of the priority areas of work in the Basin Development Strategy 2016-2020, and the Strategic Plan 2016-2020.

The MRC is currently developing a Mekong Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan (MASAP), expected to be finalised later this year. The MASAP is a transboundary climate change adaptation strategy that will offer strategic directions in climate change adaptation work in the Lower Mekong Basin countries and support relevant national strategies and processes.

In the preparation of the MASAP, a series of basin-wide assessments of climate change impacts on water and water resources and related sectors in the Lower Mekong Basin has been conducted. The climate change assessments contain seven themes and sectors. They assess impacts of climate change on hydrology, flood behaviour, drought behaviour, hydropower production, ecosystem services and biodiversity, food security, and socio-economic and vulnerability.

With these assessments, the MRC CCAI defines a wide range of potential future changes projected to occur over the next 20 to 50 years according to the GCM-based regional climate change scenarios.

Nine future climate change scenarios for the LMB were considered. They represent a combination of three levels of changes (low, medium and high) and three patterns of changes (drier overall, wetter overall, and high seasonal variation). — VNS