A new 3D supporting machine system has made surgeons' work less complicated, Thu Vân reports.

|

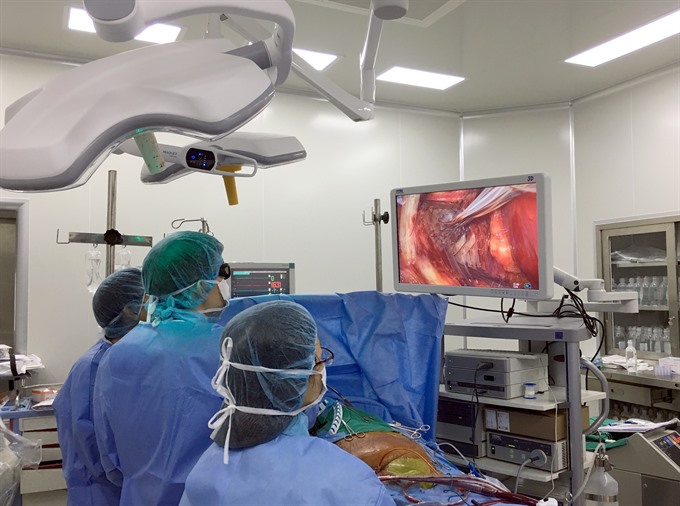

| Dr Phạm Thành Đạt and his team look at the 3D screen as they perform a heart surgery. — VNS Photo Thu Van |

by Thu Vân

At half-past 10 in the morning, the cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB pump) started running, making a steady sound.

My heart was pounding, though, and I was half-afraid I would faint. I had never seen an operation first-hand before, and I was no medical student inured to the graphics of flesh, bone and blood.

The room’s was filled with the clean hospital-aseptic tang and other odours, the iodine used to sterilise the skin, the subtler notes of the fluids.

A state-of-the-art, minimally invasive surgery was about to take place, I reminded myself to get rid of the nervousness.

Dr Phạm Thành Đạt, the surgeon, had just finished establishing the CPB for the heart surgery. The patient, Nguyễn Văn Hảo, 59, lay still on a stainless steel table, draped in a green sheet.

A gloved palm went out and Đoàn Thị Yến, the scrub nurse, placed a scalpel on it. Đạt made an incision of five centimeters on the patient’s thoracic. A soft retractor was then inserted into the incision. An endoscope with a 3D camera was inserted via another incision made about three centimeters away from the first one.

The patient had complained of fatigue and dyspnea. Three weeks earlier, he had suffered an attack of severe pneumonia. Doctors said the condition was not properly treated, and this damaged his heart’s mitral valve, necessitating surgical repair (or replacement).

The mitral valve, which has two flaps, lets blood flow from one chamber of the heart, the left atrium, to another called the left ventricle.

It was not the first surgery of this kind for Đạt, who worked at the famous Việt Đức Hospital for three years before moving to the E hospital more than a year ago.

But today, the surgery would be a bit different. The new supporting machine system, a 3D system requiring surgeons to wear 3-d glasses, could make his work less complicated, Đạt hoped.

Traditionally, this problem would have called for an open-heart surgery, requiring the sternum to be opened in order to expose the heart. This is seriously invasive stuff, and the sternum itself could take up to three months to heal fully. And many a time, with the patient already not in the best of health, the surgery carried hefty risks, Đạt said.

In the laparoscopic surgery that he had just started performing, the small incisions that Dr Đạt just cut on Hảo’s chest would be enough. The soft retractor would enable the surgeon to insert the specialised minimally invasive instruments.

Wearing the special 3D glasses, Dr Đạt and his assistants looked at the 3D screen right above the surgery bed. Images from the inserted camera were transmitted to the screen, allowing the team to see the inside of the patient’s anatomy in full three dimensions, as if he had actually opened the patient’s thoracic up.

When Dr Đạt conducted his first laparoscopic surgery a year ago, he had to work with a 2D camera. While laparoscopic was an advanced technique in heart surgery, the 2D lacked depth perception, often making it difficult to judge where incisions need to be made, he said.

“This 3D technology means we still perform keyhole surgery, with all the same benefits for the patient, but in such a way that we can see the patient’s anatomy as if we were doing open heart surgery,” he explained.

Đạt started to widen the first cut to open the pericardium in order to go deeper into the heart. Under magnification, the landscape of a part of the heart expanded to fill the screen. Đạt’s tiny diathermy knife travelled in millimetre leaps.

Opening the pericardium took much longer than usual, because of the patient’s fatty condition, and an aortic clamp was inserted through one of the incisions. This would help isolate the heart from the blood pumping system so that the heart would stop temporarily and the main surgery can be performed, the doctor said.

After he had successfully put the aortic clamp in, Đạt inserted a cardioplegia needle to deliver cardiopledia solution, and a dramatic spurt of arterial blood could be seen on the screen. Calmly, he started infusing blood cardioplegia via the needle in the cannula.

"Blood cardioplegia is a chemical substance that will keep the heart ’alive’ as it is made to stop beating during the surgery", he said.

This is where the 3D system proves itself.

“With a 2d image, it’s often very difficult and sometimes dangerous, because you can’t see the three-dimensional images of the inside. If you inserted the needle too deep that it tears down the aorta, it would cause severe bleeding, and we would immediately have to shift to open-heart surgery,” he said.

“A senior surgeon told me once that when he started with laparoscopy surgery, for two years he dared not to look at the 2D screen, only directly into incision opened on patients’ chest because he was worried the images would not be clear and safe enough,” Đạt said.

But with the 3D images on the screen right in front of him, such worries were done away with.

Thirty seconds after, the heart stopped beating. I held my breath, despite myself.

Dr Đạt then used a diathermy knife to open the interatrial groove (wall of tissue that separates the right and left atria of the heart), in order to see the mitral valve. Something unexpected came up then. Smoke and the stench of burning flesh and a hypnotic sight on the 3D screen: a blue arc of high-voltage electricity playing around its tip and a plume of smoke rising from the tissue it touched.

It was around 11.30am when the doctor finally saw the lesion in the mitral valve, which was, unfortunately, severe. He stomped his right foot, and then the left. He’d been standing for an hour and a half.

Why they like it

“Bad news is we’ll have to replace the valve,” he told the team. The image on the screen showed several perforations in the valve.

“With this new system, I can clearly see the severe lesions on the patient’s valve. That helps me make a more exact assessment and take a proper decision in this case,” he said.

As he decided that the damaged valve should be replaced, Đạt started to cut the valve with a scalpel.

As he cut each part it off, he also conducted placement of mattress sutures into the mitral annulus (a fibrous ring that is attached to the mitral valve leaflets).

“This is also a risky procedure, where an extra move could damage the aortic valve or hurt the coronary artery… putting the patient’s life in danger,” Đạt said.

Again, with technology that works a lot like the 3D projection systems in movie theaters, the surgical team can see the anatomy from all angles and perform the procedure faster with greater accuracy.

“And now you see that’s why as a cardiovascular surgeon, I personally feel new technologies like this 3D system support us effectively. We are able to operate more smoothly in respectively shorter surgery times and limit risks considerably,” Đạt said.

Relatively shorter was right. The surgery was successfully completed at 6pm, almost eight hours… a full, normal working day, for just one operation.

Lê Ngọc Thành, director of the E Hospital, said the 3D technology was first used at the hospital in early December on a patient from Nam Định Province with an atrial septal defect.

The patient was hospitalised with chest pain, breathing-difficulty and fatigue. Weighing only 34kg, it would be risky for her to undergo an open surgery. With the newly-equipped 3D system, Thành performed laparoscopy surgery on the woman, who was discharged after six days in stable condition.

3D printed hearts

While 3D technology has been applied in other kinds of surgeries, it was the first time that a hospital in Việt Nam was using it for heart surgeries.

“This is a major step forward, because with the images that have been zoomed in many times, doctors can operate more easily and accurately, reducing the surgery time and reducing the risk for patients,” said Nguyễn Công Hựu, head of the Cardiovascular Surgery Department at the E Hospital.

“Imagine... with the 2D technology, you were driving an old-fashioned car, but with the 3D technology, it’s a modern Lexus: much more comfortable, effective and safer,” he said.

“I hope that some day 3D-printed soft artificial hearts will be available in Việt Nam so that we can reduce the risk to the minimum and give those unfortunate to have weak hearts the chance to have healthier ones,” Hựu said.

As I walked out of the operation theatre, I felt I had seen something miraculous in more ways than one.

As lay persons, the miracle of the human body is something we take for granted, and the miracle of modern technology that helps save lives is not something we get to see everyday. — VNS