Expat Corner

Expat Corner

Joshua Zukas

If you haven’t experienced it, you probably don’t get out enough.

You arrive for a short break at one of Việt Nam’s quintessential countryside destinations. The views from your rustic lodge are sublime. Streams meander through lofty rice terraces. Pockets of cloud cling to jungle-topped karst mountains. The rice paddies emanate a green so fanciful that it’s bordering on nuclear.

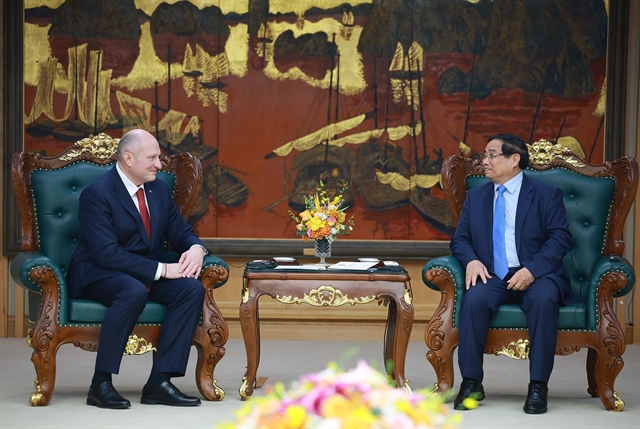

|

| Singing in standard soundproof rooms is legal in Việt Nam. — Photo baogiaothong.vn |

But somebody, somewhere, is howling into a microphone, plunging the celestial landscape into an aural inferno with their brazen self-confidence.

Maybe you accept it. It’s Vietnamese culture, you chuckle to yourself. It’s not that bad, you try and convince your travel buddies. You’re not going to let a distant but persistent racket wreck your holiday. The warbler – perhaps a fellow tourist in a nearby hotel – wants to enjoy their holiday just as much as you do, and that’s fine. The Vietnamese don’t seem to mind, so why should you?

But do the Vietnamese mind?

Recently I learned of a term for this kind of noise pollution that may reflect changing local attitudes: quốc nạn.

It means “national disaster” and expresses all the playful melodrama and linguistic ingenuity I’ve come to expect from a Vietnamese coinage. My Vietnamese friends seem increasingly embarrassed about this national disaster. It’s not our culture, they assert. It is that bad, they retort. And it needs to stop.

Some Vietnamese are starting to mobilise. Two years ago, a news video featuring cheerful tourists singing karaoke in coracles outside Hội An drew condemnation from Vietnamese netizens. “Why don’t they go to a nightclub?!” somebody commented in Vietnamese. “I am feeling sick,” wrote another in English.

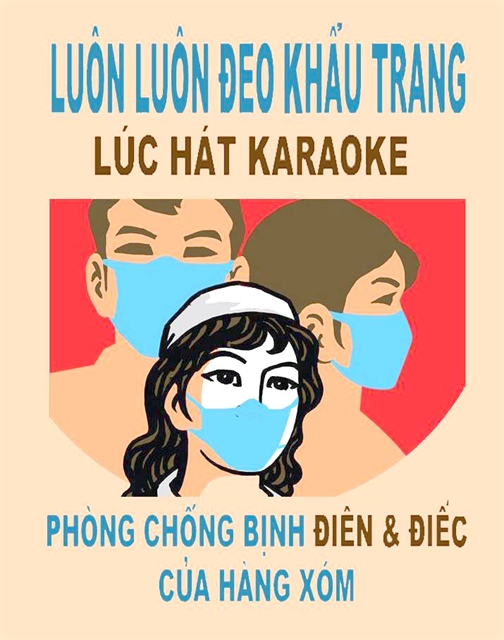

More recently, a parody Covid-19 poster depicting masked people has started to circulate. Translated it reads: “Always wear a mask while singing karaoke to prevent your neighbours from going mad and deaf.”

Now don’t get me wrong. I like karaoke just as much as the next (Vietnamese) person. When the disco lights align and the rice wine flows, there’s nothing better than greedily snatching a mic and belting out a few Disney classics. Sometimes I just need to Let It Go, embrace The Bare Necessities of life and lose myself in A Whole New World.

|

| A poster that reads "Always wear a mask while singing karaoke to prevent your neighbours from going mad and deaf". Photo courtesy of Nguyễn Quí Đức |

But, willfully ignoring the time I gave a horrendous and very public performance at a wedding, I’d rather keep my karaoke behind closed doors and more importantly, in a soundproof room. Why go deep into the glorious Vietnamese countryside just to taint the pristine environment with my bluster? Why would I want to deafen perfect strangers?

This national disaster has got me thinking. Is karaoke something we – foreigners – have the right to complain about? I’ve been living here on and off for over a decade, and I’ve experienced nothing but gracious hospitality from the Vietnamese. I’ve not once been made to feel like I don’t belong. Every day I have warm and genuine encounters that would put my own country people to shame. There’s nowhere else in the world I’d rather live.

One of the last things I’d want to do in this world is disrespect local culture – and that goes beyond Viet Nam. I’d never grumble about the call to prayer in Indonesia, even if it does wake me up at the crack of dawn. Nor would I groan about the playing of the national anthem in parks in Thailand, even when it obligates me to stand there for three or four minutes, disrupting my outdoor workout.

“I wouldn’t complain about karaoke in Việt Nam,” a foreign resident in Hà Nội told me. “It’s an expression of culture.”

|

| Singing karaoke in an open space can cause disturbing noise to the surroundings. Photo vntintuc.net |

“I would,” argued another. “It’s not the same as disrespecting religion.” But I’m uncomfortable with this distinction. We can complain about disruptive cultural practises, but not about disruptive religious ones?

“Of course you can complain,” an indignant Vietnamese friend tells me regularly. “I complain, so you can too.” Maybe that’s the answer: Foreigners can have gripes about local life, but only when the locals have them first. VNS