" />

|

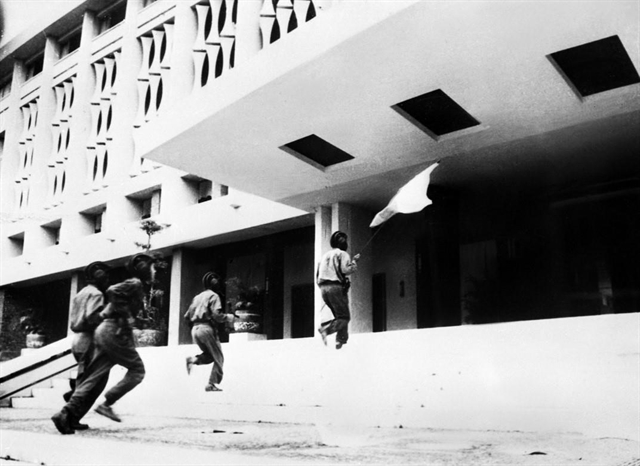

| Illustration by Đỗ Dũng |

By Phan Triều Hải

Ever since her 32nd birthday last year, Vy had been afraid of gaining belly fat. So instead of eating cheese and drinking lots of beer before sleeping, the couple only drank two small glasses of beer at dinner. The weather in Sài Gòn encouraged beer consumption. Cao thought Sài Gòn was the best place to drink.

This city had all sorts of problems: crowdedness, noise, heat, suffocation, traffic, lack of hygiene, pollution and beer was the solution that could dissolve all these issues in the fastest way. A gulp of beer enabled people to endure and relax, and made them irritable but energetic enough to do unexpected things.

Beer lovers would never feel tired of Sài Gòn. Nor was there a better place for beer to show off its ability to excite, relieve stress, connect friends or accompany a solitary person.

Nevertheless, Cao rarely went out to drink. He wasn’t social. Cao always wanted to be alone. His world was minimalist, just enough. And that world had become smaller ever since he got married, so much so that his wife condensed into a space just enough for the two of them, without any room left for anybody else.

That crowded space, along with several habits that had become rituals such as drinking in small glasses or getting in touch with each other through an old-fashioned desk phone, had formed a small kingdom with two people who focused on living and working according to their own standards. There, the big differences in age or height were gone. There, Cao felt comfortable and safe.

Or at least that was what he used to think.

“Our city is getting more and more crowded,” Vy said while pouring beer into two glasses which were lying neatly in her grasp.

“Hmm.”

“Everybody flocks here to make a living, stays and procreates. I think it’s going to explode.”

Cao remembered the sight outside the window of the express train which 36 years before had taken him down along the country to Sài Gòn. A journey filled with leafy trees and bundles of thick wattle fruits threading through the train window. Was she talking about me? Cao thought silently.

“If there’s some better place to live, we should consider it,” Vy said.

The best place to live was the most familiar place. Cao thought again. But instead of saying it out loud, he took his first sip of beer at dinner.

“My friend has returned from America,” Vy said. “She went there to deliver her baby.”

Cao often heard such stories but didn’t care much. Because in order to deliver a baby, one would have to be able to fertilise first - an issue that had become increasingly difficult for many people. Only then could one afford to choose a place for delivery. There were so many things one couldn’t control.

“She was wearing her hanbok to cover her seven-month pregnant belly when going through customs.”

Cao wasn’t crazy about Korean soap operas, but could easily visualise a woman in a hanbok. Nevertheless, a seven-month pregnant belly underneath was something he couldn’t imagine.

“Have you ever thought about living somewhere else?”

“Where?” Cao said, “is there any place more comfortable than this?”

“Do you really think this is for us?”

“Sài Gòn is filled with opportunities. You can still go wherever you want.”

Vy pursed her lips, and looked straight at him. Cao thought he should stand up to get a beer, but didn’t dare to. This conversation wasn’t like previous ones. Vy spoke slowly, word by word, as if she were explaining a simple thing to a child.

“Travelling is different from living. If there are better places for living, why shouldn’t we try?”

Cao felt his face burning.

“If you keep comparing one thing to another, you’ll be miserable.”

“I don’t compare. Those things are obvious. You see them but ignore them.”

“Only you think so.”

“Everybody has the same amount of lifetime, but their life stories are different. Why? Because of where they live, and what opportunities they have.”

Vy’s fingers clutched at the edge of the table, the palms of her hands hidden underneath, the tips of her fingers subtly turning pale like a mountain climber using all of her energy to cling to a cliff. Cao didn’t remember when she had last spoken at such length. Vy rarely spoke much. She often spoke succinctly, sometimes curtly.

“A good place for one person may not be good for another person,” Cao exhaled, stood up, and said “I’ll go get more beer.”

“What’s so good about a life without change? “ Vy said, sighing.

***

In the summer, out of the blue a group of old friends organised a reunion. Cao saw several friends whom he thought had disappeared at sea many years before.

After telling their names, everyone needed a while to get used to the old men who had replaced the children who used to be close friends at 12. Everything remained the same in a different body.

Yet only Huy stayed the same even in appearance. Huy was still short and seemed unable to gain any inches in height throughout all the years. What Cao remembered most was the time after school, instead of going home the two of them would walk straight into Mạc Đĩnh Chi cemetery, sit with their feet dangling on the white cement tomb and together read and re-read a book they had bought from a scrap vendor, Chekhov’s Short Stories. Then one morning, Cao stood dumbstruck in front of the old wooden door of his friend’s house which was shut tight with a pitch black lock. Huy had disappeared with his family.

“I still have that book,” Cao said.

The book had followed Cao all those years, even though he didn’t take good care of it. Every few years, it popped up somewhere, in an old drawer, under the bed and most recently, Cao found it lying among a pile of paper soon to be thrown away. Cao thought he would give Huy that book as a gift. It existed, because it belonged to somebody else. It could wait.

Two small glasses were replaced by three sparkling beer bottles, which made the atmosphere much livelier. Throughout the dinner, Vy listened to the two old friends taking turns telling silly stories: their reading Chekhov’s love stories on a pile of deadly white human bones until dusk, having a crush on the same girl and more.

While the two men slowly turned into boys, Vy sat with her chin on her hands, smiling.

Cao realised Huy remembered many things from those years. All stories had Huy in it, but they mostly resided in Huy’s mind only. Perhaps space affected people’s memories, Cao thought. If he were a scientist, he could make money by researching how space affected emotion, how emotion nurtured memories. Not a bad idea for research. As the stories dragged on, they were solely told by Huy and thickened into a dense fog.

Cao wasn’t listening as attentively as earlier. He was letting himself bob in that misty sea, contemplating the woman sitting in front of him flickering ethereally. She was too charming, too light-footed. As always. Ten years before, when he first saw Vy, he was dazed. That beauty didn’t seem to change with time, yet he seemed to be re-discovering it now.

Cao realised his wife was more beautiful than most women he saw every day. When he didn’t look, who would look at her? Cao felt annoyed. Through all those years, when she was forgotten, did those pairs of eyes and lips become invisible or quietly offer themselves to the crowd?

That night, drowning in his wife’s brilliant beauty along with a little jealousy, Cao struggled to prevent the headboard of the bed from pounding into the wall while Vy bit deeply into a corner of the pillow to prevent any noise from disturbing the dining room where Huy was sleeping for the night on a long couch. If throughout all those years Cao had always been as powerfully aroused as he was now, perhaps they could have had a baby, Cao thought.

“I don’t want to have a baby now,” Vy whispered.

Vy’s chest heaved. She looked like an exhausted salmon after a jump against the current. Yet not every salmon laid eggs. There were always exceptions.

“If we had a baby, our meals would be more fun,” Cao said as he slowly pulled a long thread of Vy’s hair from his mouth.

“Babies aren’t for fun,” Vy said quietly, unclasping her hands from Cao’s back, dropping them on her sides. “First we have to make sure our baby will have a good life.”

Cao breathed lightly, and covered her body with his shirt. Vy lay silently, closing her eyes, not to sleep but to think. There was a perfect stillness all around, outside and even in here. Cao found himself so cruel because he fell asleep at the usual time on the day he was reunited with his best friend after so many years of separation.

***

While Cao struggled to worm his way through the traffic in rush hour, Huy tried to get used to sitting in the back without holding on to the grab rail in the rear. Huy didn’t want to betray the fact that he came from another place. The closer they approached their destination, the more nervous Huy became.

“In the old days, when I first saw Lai sit by her piano, I understood that she was beyond our grasp.”

Yes. In those days, that was what Cao thought too. Cao remembered how the lustrous dark brown wooden piano overwhelmed them all. He remembered the piano and the chair as a secret treasure, because the piano was filled with musical books inside.

“I used to think that it was the only piano in Sài Gòn. “

“Or the most beautiful.”

“Surely it was,” Huy said.

Lai was still living in a house just across the street from school. She was sitting in front of the house, resting on a fabric-covered chair whose corners were worn-out and torn. Lai recognised her two former fans, but only smiled gently as if today were Thursday, the only day of the week when the whole class finished school early at 3pm and dropped by to have a chat. She silently brought out two small plastic chairs and placed them by the door.

Huy and Cao looked at each other, then sat down.

Lai still looked petite and light-skinned even though she had a few marks of melasma on her cheeks - the sign of post-delivery in some women. Cao suddenly wondered since when he had started to pay attention to such details. Behind her were packs of coke and beer piled on top of each other reaching up to the ceiling. On the shop window Cao saw a wrapped gift bag containing a red box of Cosy biscuits, a bright yellow pack of Lipton teabags, a box of instant Nestlé coffee, a bag of Bibica sweets and a dark brown bottle of Đà Lạt wine. The cellophane wrapping paper looked dated and soft, dull and dusty.

Cao glanced at a few threads of hair on Lai’s head and a few crow’s feet around her eyes, which wasn’t too bad for a single mom. He could still see clearly the spirit of the 12-year-old girl of old.

In those bygone years, nobody ever saw Lai sad. She cheerfully and easily glided past annoyances exactly like the way she was welcoming her two friends now, not too ardently but warmly. No wonder everybody liked her. No wonder on an afternoon at the cemetery, Huy and Cao tore away their pledge of brotherhood written on the cover of Chekhov’s Short Stories when they argued which one of them had the right to pursue her.

The three friends sat in silence for a while. Lai turned a small electric fan to face her friends. The blades swirled crazily but didn’t provide much relief.

“I used to follow whatever my parents planned for me,” Lai said, “from career to relationships. Then I met a man, gave birth, broke up and did what I’d never done before. Nothing in life happens as planned.”

Everybody who was alive was writing his or her own book. Lai was telling her story. Cao didn’t know if the book of his life was interesting.

“Even without planning everything keeps flowing,” Lai said. “Life turned out to be simpler than what my parents feared.”

“I’m different though. I always plan how to pay the bills. Rent, insurance, food, gasoline. Everything has to be accurate. Every month is the same. Always the same,” Huy said.

I lived by habit, Cao thought. But perhaps habit was also a type of repetitive planning. It was fortunate that in those days neither one of them won their battle for Lai. Or else, whoever had her would have found himself in either a tragedy or comedy. Cao tried to focus on his friends’ stories.

“Unable to read or deal with traps, I’ve chosen to close my eyes and walk through them. I don’t care about the ugly or beautiful scars they’ve left, as long as I can walk through them,” Lai said.

***

On his last evening in Sài Gòn, Huy drank a lot. When the short hand pointed to ten, he said he would leave in five minutes. Huy often spoke thus about his intentions, which Cao found to be quite a good habit. It was always pleasant to find oneself with a plan, however small.

There was only a plate of cheese left on the table. This piece of cheese had been bought at the beginning of the year at a discount price. It had lost its freshness and turned a little dry, but still felt buttery. Cao brought three bottles of beer and put them down in front of each one of them.

The bottles clanked up against each other on the neck like a bundle of mangrove roots, then separated. The three sipped their beer gently. They had drunk a lot already.

Vy rested her chin on her arms for a while, then spoke without looking at Cao.

“I think there’s only one way for us.”

Cao needed a few seconds to figure out who was speaking, and a few seconds more to understand whom Vy was speaking to. At last he realised Vy was addressing him.

Cao looked at Vy, but she was only staring at her bottle.

“We can have a fake divorce,” Vy said. “After that, I’ll marry a man who lives there.”

Cao needed a long while to understand. Then his body, from the head to the neck to the shoulders, suddenly turned hard and numb.

“It’ll only take a few years,” Vy took a sip of her beer and continued, “Then everything will return to normal.”

Everybody fell into a long silence. Cao felt his neck relaxing a bit, and seemed able to turn his head gently, but he didn’t try. Only his two eyes seemed to be moving now. Cao saw Huy drinking silently. As for Vy, her face looked calm again, as if she were still indifferently listening to trivial stories.

“What were you thinking when you said that?”

“It’s just a plan. We’ll discuss it in detail.”

“How could you say that?”

Cao repeated his question, chokingly. He felt he couldn’t take in anything, even air.

“If we can choose a better place to live, why don’t we try?” Vy said. “You only have one life to live. Whether you’re willing to change or not, your life will end anyway.”

“We’re enjoying a better life than many people, so why should we change?”

Huy gulped down his bottle in one go, then looked at his watch.

“I have to leave.”

Cao looked at Huy as if the latter were some stranger who had suddenly appeared in his house from out of nowhere. It took him a second to recognise his friend. Huy walked toward the desk phone to dial. Huy spoke to the switchboard operator, confirmed Cao’s address and phone number, than hung up. Since when did he remember Cao’s home phone? Huy said nothing, patted Cao’s shoulders gently and walked to the door. Vy followed.

Cao sat alone, listening to the clanking sound of Vy locking the gate from the yard.

***

Cao wasn’t a mean person. He’d never complained about a dish, whether it was served on a china plate in an expensive restaurant or on a plastic plate on the sidewalk. He could adapt to annoying circumstances, like when he could still focus in a movie theatre despite others’ noisy conversations. Everything was something to experience, Cao thought. It was life. Whether it was ugly or beautiful, everything was worth enjoying.

Yet Cao had a bad instinct. Instead of simply looking at the surface, he often searched for the truth. Instant noodles for dinner would be normal if both he and his wife went home late. But it would be a different matter if it was the result of laziness and carelessness. He would consider a bunch of noisy customers disturbing his time in a restaurant on the weekend a mere entertaining show offered to him free of charge. But if they intentionally wanted to destroy his meal, it would be a different story.

That was why what Vy said that evening was as good as putting an end to their marriage.

***

For two weeks Vy didn’t go home. Nor did she answer her phone.

Cao started to get used to living without her, and didn’t need to fill his emptiness by trying to meet one friend or another like in the first few days after she left. Cao phoned her parents. In a calm and somewhat distant tone, they told him that she was alright, and that he had nothing to worry about.

Cao felt himself quite cruel because he felt fine. Ever since Vy proposed her crazy plan, she had become half a person in his mind. She appeared in his memory with only her left half or right half, half of her hair, one eye, one ear, one nostril and half of her mouth.

Of course half a person wasn’t beautiful and didn’t evoke any emotion. Cao found himself able to forget her very quickly. Yet he resisted, because if she was gone from his memory, which meant that she was right, then all those years were indeed worth nothing.

Downstairs, the desk phone rang loudly like a fire alarm or an ambulance siren, startling Cao.

It could only be Vy. Only Vy called the desk phone. It wasn’t just the secret signal between the two of them amidst a topsy-turvy world dominated by social media, but also one of the foundations of their small family.

Yet at that moment, Cao felt weary to his soul.

He stood still, letting the phone ring until it stopped.

She would call back for sure, Cao thought. Women were emotional and impatient. Especially Vy. She couldn’t wait for change to come to her, but must change herself right away.

Cao quietly opened the fridge, and took out the last bottle of beer. Holding the green bottle, he remembered he hadn’t drunk beer in a glass for a long time. Did every collapse start with the breaking of a small principle? Suppose he was drunk in the old way now, would normalcy return?

Cao looked at the desk phone which was lying there in silence.

Ten minutes passed, but Cao felt like going through an eternity. She would call back for sure, Cao thought. She would call back. He still understood her better than anybody else.

Right then the phone rang.

Cao slowly put the beer bottle on the table, took a deep breath, suppressed the throbbing in his chest and picked up the phone.

“It’s me, Huy.”

Cao tried to suppress a sigh.

“Are you two drinking beer?” Huy asked.

The signal buzzed a bit, then became clear again.

I just wanted to tell you I’m getting married.”

“What? To whom?”

“Lai” Huy said. “She’s decided to follow me at last, for her child’s sake.”

Cao said nothing.

“But it’s true love to me, we’ll be a real couple,” Huy said

For a child’s sake. Cao didn’t know that feeling. A real couple. Cao doubted it. After many years believing he had everything, Cao found himself empty-handed.

“Hope you aren’t jealous.”

“No, not at all,” Cao said quickly.

Huy hung up.

Cao remained dazed for a while, then slowly walked toward the table to pick up the beer bottle, and took a sip. The afternoon sunshine had been heating up the beer. Never before had he tasted such hot, bland, spiritless beer.

He needed to put the beer in the fridge. But instead of doing so, he sat down on the chair, and clasped his hands around the hot bottle on the table.

I need cold beer.

Cao tried to speak aloud, but his body didn’t budge. He seemed to be cast to the wooden chair and turn into wood, unable to stand up anymore. VNS

Translated by Thùy Linh