Environment

Environment

.jpg)

A century ago, a woman from Thượng Trạch Village married a man in Liên Chểu Village, Triệu Sơn Commune, Triệu Phong District, connecting the fate of the two villages by the craft of vermicelli-making and an environmental problem.

|

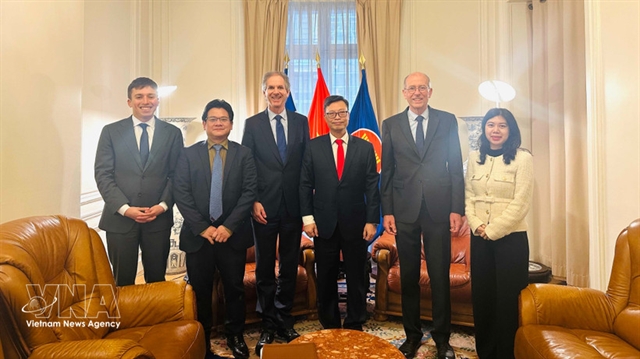

| Nguyễn Đăng Đức in his vermicelli workshop. The man says he will move to the common hub despite being used to traditional practices. — VNS Photo Khoa Thư |

Khoa Thư

QUẢNG TRỊ — A century ago, a woman from Thượng Trạch Village married a man in Liên Chiểu Village connecting the fate of the two villages by the craft of vermicelli-making and an environmental problem.

At the time, Thượng Trạch in Triệu Sơn Commune, Triệu Phong District, was famous in the central provinde of Quảng Trị for its specialty noodles. The industry soon thrived in Liên Chiểu Village as the woman taught people there how to make them.

Nowadays, Liên Chiểu has surpassed Thượng Trạch in the number of vermicelli-making households, with nearly 70 workshops.

The booming industry however has led to a thorny problem of how to deal with the wastewater.

For more than 100 years, vermicelli-making workshops have been located in each family’s house.

“Waking up in the morning, noodle makers can start grinding rice flour in preparation for the first batch before having breakfast. They find it easy and convenient as there is no need to leave home,” said Nguyễn Hữu Vãn, head of Triệu Sơn Commune People’s Committee.

“The practice has been maintained for such a long time that no one wants to change, despite the fact that the local environment has been severely destroyed by untreated wastewater directly discharged into irrigation systems and paddy fields,” he added.

Year-round, the village smells of sour fermented rice starch. With 12 tonnes of vermicelli produced a day, households in Liên Chiểu Village generate some 150cu.m wastewater, all absorbed into the land.

Meanwhile, local people depend on groundwater for daily use and noodle production, exposing themselves to a higher risk of diseases.

In 2015, a plan to develop a vermicelli co-operative in Liên Chiểu Village was proposed to Quảng Trị People’s Committee in which wastewater treatment was highlighted as the most important task.

A taskforce from the Huế University of Science was deployed to Liên Chiểu Village to seek solutions to the problem.

A waste collecting system with pipes connecting each household with a centralised treatment plant was presented yet the expenses were too high to handle.

Local authorities decided to switch to plan B of relocating all vermicelli workshops into a common hub, far from the residential area.

That was when traditional practices and authorities' vision collided.

|

| Rice is ground into powder each morning to make vermicelli. — VNS Photo Khoa Thư |

“Personally, I do not want to move,” said Nguyễn Đăng Đức, the vermicelli master’s fifth-generation descendant, while pulling shiningly white noodles out of a machine.

“We are used to staying at home. Relocating means we will need to invest in a brand-new workshop which usually costs VNĐ70 million (US$3,000),” he added.

“However, if local authorities request, we will follow. The pollution is reaching an unbearable level.”

More than VNĐ4 billion ($172,500) has been allocated from the public budget and international fund for land clearance and wastewater treatment plant construction.

“A biogas system is under construction to turn wastewater into energy,” said Vãn. “It also costs less than the use of probiotics while households can use gas to cook vermicelli,” he said.

To encourage workshops to relocate, Triệu Phong District People’s Committee plans on offering an incentive of VNĐ15 million ($650) for each.

“Otherwise, there is also a mechanism to force those refusing to move to stop making noodles in the residential area,” said Phan Văn Linh, head of Triệu Phong People’s Committee.

A total of $15,000 has been sponsored by the Ford Foundation via a group of master's students of UC Berkeley and East Anglia University to build sumps and train local people how to track indicators of treated wastewater.

“They will be equipped with handy tools to check the quality of wastewater. Community supervision is critical for a craft village like Liên Chiểu since residents are also direct victims of pollution,” said Nguyễn Nam Anh, a representative of the student group.

The plan is considered “revolutionary” for the village, Vãn said, as it not only gathers all workshops under one umbrella but also creates favourable conditions for local vermicelli to be certified as a speciality following the governmental 'One Commune – One Product' (OCOP) programme, which is meant to urge each locality to come up with or pursue a product to their advantage in order to boost economic development.

“We expect to finish constructing the hub by the end of 2020 and relocate workshops by 2021,” said Vãn

“Although the COVID-19 pandemic has slowed the schedule, local authorities are trying our best to stick with the initial plan,” he said.

“We simply cannot wait any longer.” — VNS

.jpg)