Features

Features

George Burchett spent his youth in the Cambodian capital, he reflects on peace and war.

|

| On the water: George and Peter Burchett – Kep, Cambodia, 1965. Photo courtesy of George Burchett |

By George Burchett

From 1965 to 1969, my family lived in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

My family included:

- My father, Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett, born in Melbourne, Australia in 1911.

- My mother, Bulgarian journalist and art historian Vessa Ossikovska, born in Lukovit, Bulgaria in 1919.

- My brother Peter, born in Peking, People’s Republic of China, in 1953.

- Me, George Burchett, born in Hà Nội, Democratic Republic of Việt Nam in 1955.

- My sister Anna, born in Moscow, Soviet Union in 1958.

We moved to Phnom Penh from Moscow, so that my father could be closer to the “action”: the war that was raging in neighbouring Việt Nam and that he was reporting on from the “communist” side, the Hồ Chí Minh and ‘Việt Cộng’ side.

1965 was a turning point in the Việt Nam war. The US-backed Sài Gòn regime was losing the war in the South. In March, the US started bombing the North and US Marines landed in Đà Nẵng, thus committing American combat troops to the war.

Before we officially settled in Phnom Penh, my father had twice crossed the border between Cambodia and Việt Nam clandestinely: on his way in and out of the liberated, Việt Cộng-controlled zones of South Việt Nam which he was the first Western reporter to visit in late 1963, early 1964 and again in 1964-65. He told that story in his book, Vietnam: Inside Story of the Guerilla War, published in New York and then worldwide in 1965.

Most outside observers and Cambodians would agree that the years 1965-69 were, to quote distinguished American journalist and New York Times editor Harrison Salisbury, Cambodia’s “halcyon days”, a period of relative peace and prosperity.

Prince Sihanouk, Cambodia’s Head of State, had performed miracles of diplomatic acrobatics to keep the Kingdom of Cambodia neutral, while a cruel war was raging in neighbouring Việt Nam. All kinds of pressures were exerted on Sihanouk by the US to force him to join the South East Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO) and become a US ‘ally’ (or puppet) in its crusade against communism.

In May 1965, Sihanouk broke diplomatic relations with the US and closed the American Embassy in Phnom Penh. Relations were only restored in July 1969. Sihanouk was deposed in a CIA-backed coup in March 1970 and Cambodia’s descent into hell began.

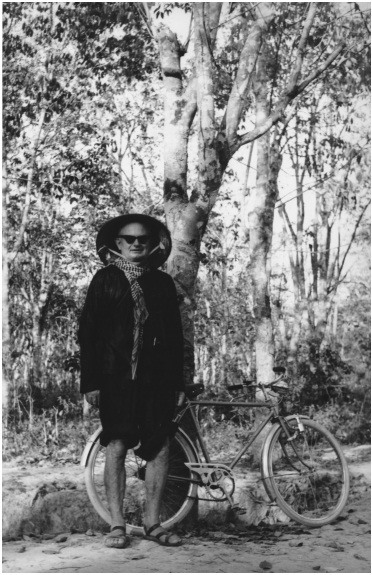

|

| Finding peace: Wilfred Burchett in the Liberated Zones of South Việt Nam, 1964-65. Photo courtesy of George Burchett |

What is beyond doubt though, is that during our four-year residency in Phnom Penh, Cambodia was a haven of peace in a very troubled region. Sihanouk was playing a balancing act between the West, mostly France, the Soviet Union, the socialist bloc and China, for the greater benefit of his small, but strategically important country. The Soviet Union was building modern hospitals and educational facilities and staffing them with Soviet doctors and educators. France had a dominant presence in all fields: military, education, health, culture, etc.

In September 1966, General de Gaulle visited Cambodia and made his famous Phnom Penh speech in which he supported Sihanouk’s doctrine of neutrality and advised the United States of America to learn from France’s colonial experience and defeats and cut their losses and leave Việt Nam.

So, in 1966, Cambodia’s neutrality was supported by one superpower, the Soviet Union and a major independent western power, France, Cambodia’s former colonial ruler. In May 1966, Chairman Mao Zedong launched his Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, which would plunge China into chaos until his death in 1976. In 1961, the Soviet Union and China had split along ideological lines and eventually became bitter foes. But both supported Việt Nam’s struggle against US imperialism and pledged friendship and solidarity. The official Soviet line at the time was peaceful co-existence and the Soviet Union was eager for the war in Việt Nam to end as soon as possible. China, on the other hand, seemed ready to fight US imperialism to the “last Vietnamese”. In 1966, much of progressive humanity was united in its support for Việt Nam’s people and their just struggle for peace and reunification.

Cambodia was peaceful and beautiful. Phnom Penh, with the bold modernist "New Khmer" architecture of Vann Mollyvann and elegant French Art Deco, was a neat and modern-looking city. To me, these are the happiest years of my life. Cambodian friends who survived the Khmer Rouge genocide agree. I remember blissful evenings at the sea-side resort town of Kep, near the border with Việt Nam. The shimmering mirror of the sea reflected the moon and in the distance, the rumble of bombs lit up the horizon. Heaven and peace on one side, hell and war on the other.

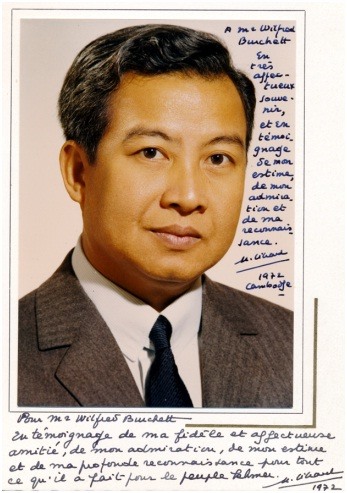

|

| A lot of respect: "For Mr Wilfred Burchett, as a token of my faithful and affectionate friendship, my admiration, my esteem and deep appreciation for what he has done for the Khmer people." -- Norodom Sihanouk, 1972. Photo courtesy of George Burchett |

There was a huge worldwide movement to stop the cruel war and bring peace to Việt Nam. Our house in Phnom Penh was always full of visitors from around the world on their way to or from Việt Nam: journalists, diplomats, peace activists, scientists, religious leaders, etc. And there were mysterious “uncles from the jungle”, who we knew had crossed the border from war to peace, to bring news of the struggle in South Việt Nam.

War and peace. At that time, peace seemed to be winning. There was not the smallest doubt in the Burchett family that Việt Nam would win. In 1968, my father wrote a book titled VIETNAM WILL WIN! The book’s title page states: Why the people of South Vietnam have already defeated US imperialism – and how they have done it – by the internationally famous Western correspondent whose first-hand dispatches from Vietnam have become a part of the history of our time.

The 1968 Tết Offensive shook US public opinion and turned it against the war. President Lyndon Johnson agreed to talks to end the Việt Nam War. They began in May 1968 in Paris. Hopes for peace were high!

But in November 1968, Richard Nixon was elected President of the United States of America and the peace talks were frozen.

In June 1969 we left Phnom Penh for Paris, where the action seemed to have shifted from war to diplomacy. In March 1970 Prince Sihanouk was deposed in a CIA-backed coup. South Vietnamese troops invaded Cambodia, supported by US bombs. Thus began Cambodia’s descent into hell. And another five years of war for Việt Nam. Neutrality and diplomacy had failed. The US had extended its anti-communist crusade to another peaceful country.

|

| Family snap: The Burchett family in their house in Phnom Penh in 1968. From left to right: Peter Burchett, Vessa Burchett, Wilfred Burchett, George Burchett, Anna Burchett. Photo courtesy of George Burchett |

The American War against Việt Nam, Cambodia and Laos ended in 1975 with the total defeat of US-backed puppet regimes in South Việt Nam, Cambodia and Laos.

But the war of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge against their own people – and their military attacks against Việt Nam– would last until 1979, when Việt Nam put an end to the criminal Pol Pot regime and saved the Khmer nation from genocide. If ever there was a case for humanitarian intervention, that was it!

But instead of applauding Việt Nam, the “international community” – the US, its allies and China – denounced Việt Nam as an “aggressor” and supported the remnants of the Pol Pot regime in every possible way, thus prolonging the suffering of the Cambodian people and “punishing” Việt Nam with ostracism and sanctions. If ever there was a blatant case on international hypocrisy and double standards, that was it!

For me, Cambodia will always remain a symbol of peace and bliss – the happy days of my childhood. At the same time, it is also a manifestation of hell on earth: Pol Pot’s Killing Fields. Carpet bombing by waves of US B-52s turned the lovely, peaceful Cambodian countryside into a smouldering inferno. It drove the peasants mad, with pain, grief, anger and hatred, and prepared the ground for the Khmer Rouge nightmare, one of the greatest human tragedies of all time.

In Việt Nam too, peasants – men and women, young and old – had taken up arms to defend their families, villages and country against imperialist aggression. They too were bombed and exterminated in the most horrible ways. But when they won the final victory, they didn’t turn their guns against their own people. There were no massacres, no blood baths, no genocide. The cities were not emptied, the countryside was not turned into killing fields.

I would like to end this essay on a positive, optimistic note. Unfortunately, it is hard today to be too optimistic, without sounding naive and foolish. Sabres are rattling in too many parts of the world for comfort: the Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan, Ukraine, the Korean peninsula, the East Sea, Africa, Latin America... Europe lives in fear of terrorist attacks and waves of refugees. It would seem humanity consistently fails to learn the lessons of history. The dynamics of war seem more powerful than the dynamics of peace.

To sustain some sober optimism, I must turn to Việt Nam. Việt Nam defeated two great powers in its struggle for Independence and Unity: France and the United States of America. In his 1966 Phnom Penh speech, General de Gaulle acknowledged the lessons of Điện Biên Phủ and drew the correct conclusions. Việt Nam’s heroic struggles remain an inspiration to people and countries around the world. Việt Nam always showed its solidarity with the fraternal people of Cambodia and Laos. They fought shoulder to shoulder against French colonialism and US imperialism for their independence and their right to choose their own path to the future, not dictated by foreign powers.

Our world is neither heaven nor hell, it is the reality we live in. The Cambodia of my childhood is an idyllic place which now only exists in my memory. But I cherish those memories of peace and happiness. At least I have them and they are precious to me. But what about children who only know the horrors of war, occupation, exile? What happens to their minds, their hearts, their souls?

The most fundamental human right is the right to live in peace, to not be bombed, occupied, terrorised. Those who violate this fundamental right, in the name of abstract concepts or geo-political interests – and we know exactly who they are – are the true war criminals. They must be stopped. But who can stop them? That is a question all of us should ponder.VNS

Hanoi, 13 May, 2017.

|

| Ancient site: George and Ann Burchett, Angkor Wat, 1965. Photo courtesy of George Burchett |

.jpg)

.jpg)