Society

Society

Ten years ago, the Vietnamese Government sought to uplift disadvantaged ethnic minority groups in the mountainous region northwest of the country by pushing for development of rubber industry.

|

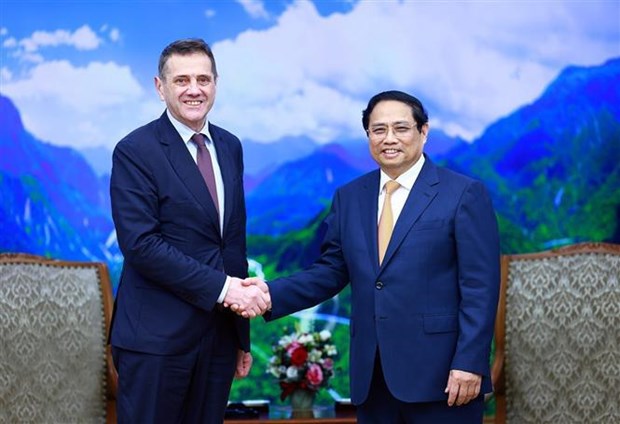

| Quàng Văn Dính, head of village Thẳm A of Tông Lạnh Commune, Thuận Châu District, the northwestern mountainous province of Sơn La. The rubber trees were planted on the land he contributed 10 years have not been harvested. — VNA/VNS Photo Lê Sơn |

Lê Sơn

SƠN LA — Ten years ago, the Vietnamese Government sought to uplift disadvantaged ethnic minority groups in the mountainous region northwest of the country with rubber plantations.

However, the promised riches from the ‘white gold’ has yet to materialise for those relinquishing much of their land to form the large-scale plantations as the latex flow continues to disappoint.

In 2017, Sơn La Province boasted one of the largest areas of rubber in the northwest region with 6,000ha. The largest was the neighbouring province of Lai Châu with 12,700ha. The expansion of rubber plantation in these localities was through a partnership where the local households ‘contribute’ their agricultural fields, used for short-term crops like maize or corn, to the local rubber company (whose parent is the State-owned Việt Nam Rubber Group).

In Quỳnh Nhai District of Sơn La Province, rubber plantations have covered the barren hills that dotted the region a decade ago.

Local people said the trees are now fully mature and the rubber could be extracted two or three years ago, but so far, harvesting has only been allowed on a small portion of the available plantations while the majority remains in a state of limbo.

Tông Lạnh Commune in Thuận Châu District of Sơn La was the pioneering area in 2008-09 to implement the project, which involves mobilising people to contribute unused land to make large scale rubber plantations. Twelve villages with 400 households in the commune collectively gave some 1,600ha for the Sơn La Rubber JSC.

A total area, 600ha was ready to be tapped many years ago but the company is yet to do so.

“Before, when they called upon the people to contribute land, they said the yield would come in seven years and the money would help people escape poverty,” Quàng Văn Dính, head of Thẳm A village in Tông Lạnh, told Vietnam News Agency.

“After the villagers handed over all their land, they only had some 12ha fields of rice left. How could we produce enough to fill our bellies with those little fields?” Dính said, adding that the villagers are feeling very impatient.

Thẳm A village handed over some 43ha of land to Sơn La Rubber JSC and the rubber trees were planted in 2008.

The villagers also complained about the company's sketchy practices, saying that only in June 2018 - ten years after the land deal was made - did the company sign contracts with them, with previous arrangements made and followed entirely by volition and unwritten agreements.

Under the canopies of the more developed rubber trees, wild plants shot up, some as high as an adult’s head while a noticeable number of rubber trees seem to be stunted.

“This is one of the rare times that I’ve got to know about how the trees are doing on my own land,” Dính said.

“I have not really come up here for a long time. The Châu Thuận farm handled taking care of the area, we normal people wouldn’t have any business to go here.”

Even those with harvestable rubber, their worries have not subsided.

“Our family contributed some 0.3ha and the entire area was tapped in 2018, but for the two years 2017-18, we received a meagre VNĐ235,000 from our shares. Some people don’t even bother collecting their shares anymore,” Lò Văn Hoà, head of village Thẳm B.

Livelihoods further suffered when they were no longer allowed to plant other crops within the rubber plantation once the rubber matured.

Throughout Sơn La, the area of harvested rubber after 10 years reached only 10-15 per cent of the planted area, a much lower figure compared to initial projections.

|

| Sơn La ethnic households are still waiting for the economic payoffs from contributing land to the State's rubber plantations but their patient might be waning. — VNA/VNS Photo Lê Sơn |

Difficulties abound

Hồ Anh Đức, director general of Sơn La Rubber JSC, said the scheme to give 10 per cent of the rubber revenues to the landowners was carried out once the first stream of rubber was collected and will continue to be done in the until the end of 2021.

This is already a vast improvement on the original policy, which states that if the company didn’t reap any profit within the first years then the participating landowners would receive nothing, Đức said.

According to Đức, Sơn La rubber trees’ quality is up to par, with decent yield at 0.5-0.6 tonnes per ha in the first years that would continue to rise in the future.

“For the rubber trees, the latex output in the three years of harvesting would not be high, in five years, the output started to climb and peak in 14-15 years,” Đức said.

In addition, rubber is a perennial industrial crop so its economic gains must be viewed in relation to the plantation’s whole life cycle and its “mixed benefits”.

Lò Văn Sâm, chair of Tông Lạnh Commune People’s Committee, said so far, planting mass areas of rubber trees has helped improve the environment – the frequently dried underground water sources in the commune are now more abundant and stable.

“As the rubber plantation widened, social infrastructures like roads, schools and cultural establishments were also built,” Sâm said.

While the long-term benefits of the rubber trees remain in the pipeline, the lack of economic deliverables certainly presents a headache for everyone involved.

Uncertain future

Rubber prices worldwide nosedived in recent times, with the current price only one third of the peak in 2010-11 period, spelling trouble for Việt Nam who export 80 per cent of its latex output.

At the same time, as the input price and minimum wage and other benefits for workers are climbing, so Sơn La Rubber JSC and the Việt Nam Rubber Group, opted to not expand the plantation area and only consolidate the existing areas.

This, in turn, creates a shortage of job, and as salary is dependent on the output and direct caretaking workload, many contracted rubber workers have quit to find better paying jobs.

Hồ Anh Đức from Sơn La Rubber said in the beginning, many landowners themselves went to work as rubber workers but the number keeps dropping. Today it is 2,500 people.

“Once the rubber reaches a certain maturity, there would not be much work to do, so many switched to other jobs. But as the harvesting begins, the company again urged them to return,” he said.

But not many are interested in returning to the infamously backbreaking labour.

According to a survey, during 2008-12, the salary of Sơn La Rubber’s worker was at VNĐ1.5-2 million per month, with some exceptions earning VNĐ3 million a month.

But in 2016, on average, a worker only posted a few working days in a month so the average salary dropped by more than 80 per cent.

Tô Xuân Phúc, a forestry expert at the US-based Forest Trends, said there needs a comprehensive review of the land contributing model on all three fronts – society, economy, and environment – as stated in the Decision 990 by the Prime Minister.

“These assessments must be done continually, and the authorities should look at the findings to modify their strategy to help shield the households from the market’s risks,” Phúc said.

He said the rubber export price would likely not recover before 2030, which would mean the contributing land to rubber plantation would bring more benefits to the participating households.

“The authorities need to take stock of how the land is being used as well as how much land each household still owns, to identify the possible causes that could lead to land conflicts and social disorder in the future and tackle them early,” he said.

“An open dialogue between the rubber company, the people and the local authorities should be held to find solutions that appeal to all stakeholders,” he added.

Professor Đặng Hùng Võ, former minister of environment and natural resources said the only way now is for the two parties to modify the contract under the supervision of the Government, with priority given to the local people.

For the moment, locals can only wait and hope for the best when the central authorities conduct review of the programme to develop rubber industry in the region. — VNS