Society

Society

In 2010, BK-Holdings of the Hanoi University of Science and Technology (HUST), signed a deal to transfer the technology of making the tricolor compaq fluorescent powder to Rang Dong Company, a large Vietnamese firm providing lighting products, for VND6.8 billion.

|

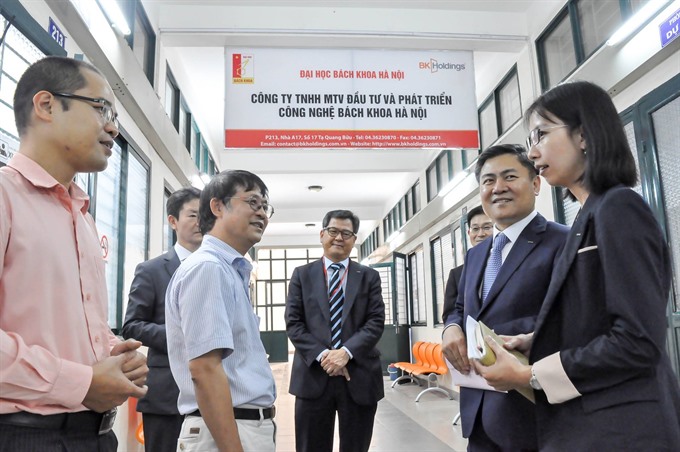

| BK-Holdings leaders met with CEO of Lotte Data Communication, Ma Young Deuk, in 2016. The two companies, along with the Vietnam Silicon Valley (VSV), the Ministry of Science and Technology, in 2016 held the LOTTE Startup Award 2016, a platform for young people to start their career in the country, introduce their products and services to the masses. — Photo Courtesy of BK-Holdings |

by Thu Vân

In 2010, BK-Holdings at the Hanoi University of Science and Technology (HUST) signed a deal to transfer the technology used to make tricolor compaq fluorescent powder to Rạng Đông Company, a large Vietnamese firm providing lighting products, for VNĐ6.8 billion (US$296,000).

The amount was modest, but the technology transferred saved the company from having to import the material, which is used to make fluorescent lamps, at a much higher price.

The deal was also one of many technology transfer deals signed by BK-Holdings, which was also the first university-implemented business model to be set up in Việt Nam, and a rarity even now.

HUST established BK-Holdings in 2008 to invest in innovative research, technological development and scientific experimentation, while conducting technology transfer and providing education and training services.

“It is well documented that universities can play an important role as seedbeds for new technology ventures, and the creation of new businesses on the basis of university research has become an important part of innovation policy in most countries, including Việt Nam,” said Nguyễn Trung Dũng, CEO of BK-Holdings, who was also selected as the Ambassador of Việt Nam by the World Innovation Forum (WIF) in 2017.

“That’s why we wanted to establish BK-Holdings, a system of businesses to capitalise on the university’s intellectual properties and achievements from its scientific research,” he said.

The objective of the company is mobilising resources from the Government, organisations, individuals and domestic and foreign enterprises to participate in the research process, incubation and commercialisation of science and engineering technology products created at the university.

The company’s operation is divided into three main spheres: education, technology transfer and incubator.

Regarding its role as a start-up incubator and accelerator, BK-Holdings’ activities include providing education and training on start-ups, and organising seminars, workshops, bootcamps and mentoring programmes for start-ups.

“With this model, we have been able to commercialise the university’s research and sign deals with enterprises to put our scientific achievements into industrial production,” said Phạm Tuấn Hiệp, director of BK-Holdings Incubator.

The company has also set up a close network with 25 training and research institutions and 150 research groups with 400 projects each year.

While the Vietnamese Government has recognised the indispensable and vibrant trend of start-ups and is doing its best to nurture the blooming ecosystem, BK-Holdings remains a rare case of a university-implemented business model in the country.

Little role

Over the past two decades, the field of academic entrepreneurship has found greater visibility across the world, and universities are becoming increasingly considered as a source of creativity among high-tech firms. Universities are moving from their traditional roles of research, teaching, and knowledge dissemination to a more advanced role of creating spin-offs and promoting academic entrepreneurship.

University spin-offs, a term to indicate a firm or organisation set up to exploit and commercialise the results of university research, were common across the globe, but were still relatively new for developing countries like Việt Nam, according to CEO Dũng from BK-Holdings.

“In Việt Nam, science and technology development is still at a low level in comparison with the world. Universities only focus on training, while the concepts of innovation, technology transfer, intellectual property and spin-offs remain unfamiliar and don’t receive enough attention,” Dũng said.

Universities’ role in the country’s start-up ecosystem remained rather unclear, the CEO said.

Tạ Hải Tùng, dean of the School of Information and Communication Technology under HUST, said the university-implemented business model had actually existed in Việt Nam for a while, but their operations were limited to only consultancy or training.

“Technology transfer and promoting academic entrepreneurship among universities is weak and rare,” Tùng said.

Dũng noted some reasons for the situation.

A lack of human resources in innovation and technology transfer was one of them.

“We just can’t use a team of people with only an academic approach like scientists or university professors to run a business with the hope of a successful spin-off,” he said, adding that entrepreneurship training among students remained unpopular.

“Vietnamese students lack the skills to create start-ups because universities do not provide adequate training and support for them,” he said.

The connection between universities and enterprises also remained loose, and funding was another crucial matter, he said.

“Universities in this country only focus on training with a limited budget, so there’s not much investment for spin-offs except for their existing old equipment or second-hand facilities,” Dũng said.

Tùng from the School of Information and Communication Techchnology added another factor that was hindering the success of university spin-offs in Việt Nam: the universities’ shares in these spin-offs.

“Spin-offs, just like start-ups, always have potential risks and require huge investment, and so they need investors,” he said.

“But universities in Việt Nam, which can only support these firms based on their reputation and the available facilities, always want to have a rather large share in the equity of spin-offs, which sometimes can be up to 51 per cent. This really doesn’t create the motivation for investors,” Tùng said.

With limited knowledge about how to run a business, universities didn’t always make the best decisions for the operation of spin-offs, he said. The fact that they had the deciding say over how the firms operated made investors hesitate.

“In fact, global experience shows that the successful rate of universities spin-offs decreases as the universities’ share of equity increases,” Tùng said.

Encouraging policies in place

In 2016, Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc approved a national education plan on "Supporting student entrepreneurship 2017-2020 with a vision towards 2025", aimed at equipping college students with the basic knowledge and skills on how to start a business, and more importantly, changing the mindsets of students regarding entrepreneurship.

According to Dương Văn Bá, deputy head of the Department of Student Affairs under the Ministry of Education and Training, the interesting part of this is that every student – regardless of their major or university – would have to learn about entrepreneurship. In other words, even medical or journalism students would need to take some business classes.

It sets out an ambitious target that by 2020, all universities, colleges and vocational schools will have completed entrepreneurship support plans for their students. All universities will be asked to have at least two initiatives or start-up projects created by students.

Bá said the ultimate goal of the plan was to make start-ups a universal concept, so everyone could learn how to start and run a business.

The journey might be long, but Tùng said at a time when innovation index is the indicator of a country’s development, promoting and fostering university spin-offs and university entrepreneurship was an indispensable choice for Việt Nam.

“This will not only contribute to the country’s socio-economic development but also create a strong momentum for boosting scientific research and high-skilled labour training,” he said.

In 2015, when Google CEO Sundar Pichai visited Việt Nam, he attended a forum with Vietnamese tech entrepreneurs. Pichai said he didn’t see any reason why Vietnamese companies couldn’t follow their counterparts in India and China.

“I think it is just a matter of time, and I think many of you are already working on something like that,” he said. — VNS