Life & Style

Life & Style

Thomas Eugene Wilber was 12 years old when his father’s plane was shot down in Việt Nam and taken prisoner. Just a day earlier, on 15 June 1968, he had received a belated birthday letter, and for sometime, believed that it could be the last thing he would ever get from his father. Two years later, he heard from his father, then interned in the Hỏa Lò Prison. His father told the family he was fine.

|

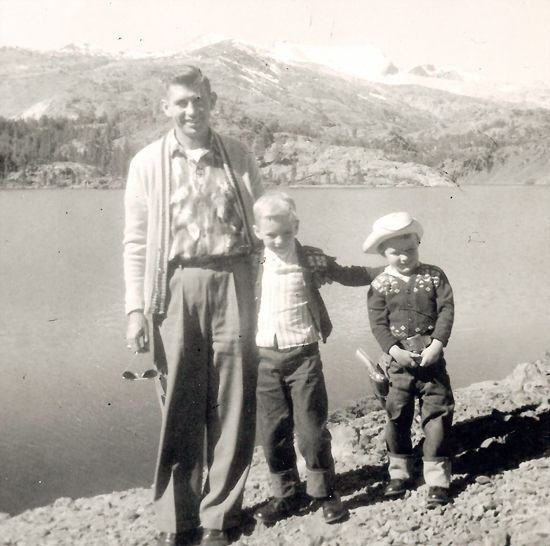

| Before the war: A photograph of Wilber (right) and his father in 1960. |

Hồng Vân

Thomas Eugene Wilber was 12 years old when his father’s plane was shot down in Việt Nam and taken prisoner.

Just a day earlier, on 15 June 1968, he had received a birthday letter, and for sometime, believed that it could be the last thing he would ever get from his father.

Two years later, he heard from his father, then interned in the Hỏa Lò Prison. His father told the family he was fine.

Forty-five years later, when Wilber had the opportunity to visit Việt Nam, the first thing he did was head to the former prison, now a famous museum.

He was surprised to see a picture of his father displayed there, opening a parcel that Wilber had himself packed 45 years ago.

In less than three years since, Wilber has traveled to Việt Nam 17 times, mostly to carry out further research on the anti-war position his father adopted and expressed while he was in prison.

The aim of his early visits was also to find out what happened to his father’s co-pilot. Subsequently, he met the person who had taken the body out and buried it after the crashed plane had stopped burning, giving great solace to the family that their loved one’s remains had been buried.

|

| Sharing memories: Wilber talks (C) chats with Vietnamese veterans at an exhibition held in Hỏa Lò prison relic. — VNS Photo Hồng Vân |

The visit also enabled him to see and appreciate the Vietnamese perspective of the war, and this understanding has increased through all visits hence.

His research has since taken Wilber to different parts of Việt Nam including Hà Nội City, HCM City, central province of Nghệ An, port city of Hải Phòng.

After his father’s death, Wilber and his family collected several items his father had preserved from his days in Việt Nam and donated the memorabilia to the Hoả Lò Prison Museum.

“I feel satisfied knowing that his personal items are in the careful custody of Hỏa Lò staff now, as his life was in the careful care of his captors many years ago. I am proud of his courage to speak his opinion for a peaceful settlement,” said Wilber.

“Having my father’s items at Hỏa Lò is a representation of someone who was patriotic to his country while calling for his country to stop a bad situation.

“I think it is important for visitors at Hoả Lò to realise that this opinion existed within the camps of detention, even though only a small number of the captives were willing to express it as vocally as did my father,” Wilber said.

|

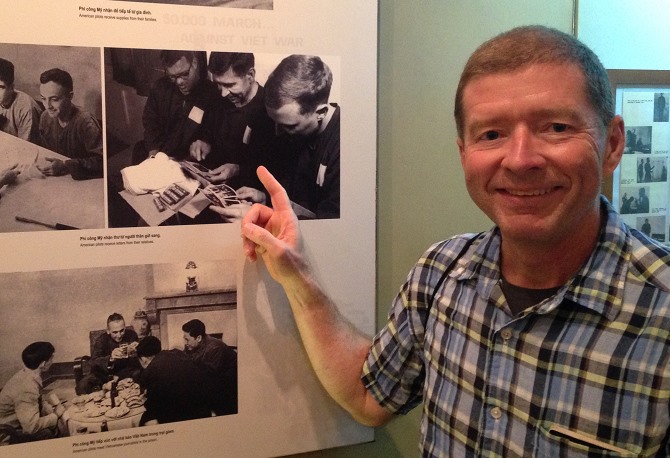

| That’s him: Thomas Eugene Wilber poses with a photograph of his father at the Hỏa Lò prison relic on his first trip to Việt Nam in 2014. — Photos courtesy of Thomas E. Wilber |

In April 1968, Walter Eugene Wilber, known as Gene, deployed his squadron heading to the Gulf of Tonkin. Two months later when his team was flying off the coast near Vinh, his plane was downed by MiG-21 pilot Senior Colonel Đinh Tôn.

Gene was kept in both Hỏa Lò prison and the detention camp in Nghệ An.

As he was led blindfolded after being captured, the elder Wilber stumbled many times, and then felt a child’s hand in his, supporting him. Thinking of his son, he gratefully accepted the support. In his first night in captivity in a village in Nghệ An, a local family treated him to a hot meal.

One time he was ill with a liver infection. A doctor examined and gave him a nature based prescription – eating many bananas. Gene followed the advice until the infection was cured, said Wilber.

Gene also had meals everyday while in the camps of detention in Hà Nội, Wilber added.

“He said he wondered if the local people ate as well as he did. I think that is why my father always insisted that if you take food on your plate you must eat it.”

|

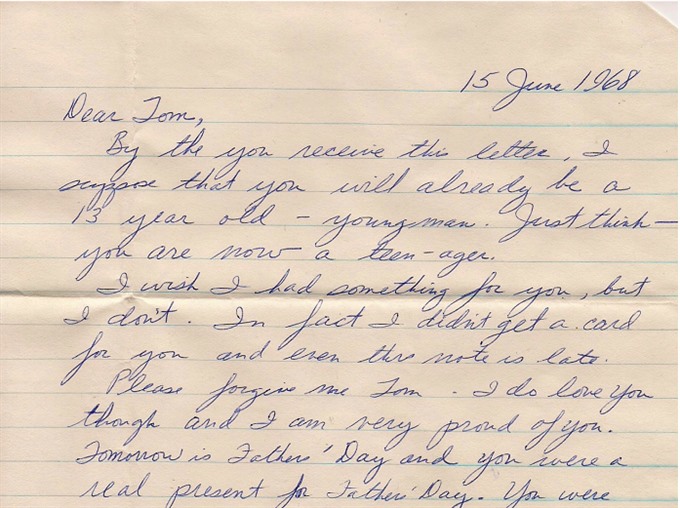

| Belated greetings: Part of the birthday letter that Gene wrote for his son’s 13th birthday. Wilber received it just a day before his father’s airplane was shot down in June 16, 1968. |

Resilience, kindness

Nguyễn Thị Bích Thủy, head of the relic management board of Hỏa Lò Prison Museum, was happy to receive Wilber’s gift. “Each original artifact adds core value to the authenticity of our display. The memorabilia that Wilber presented has significant meaning for us as we are pushing to collect more documents and memorabilia from former American pilots and their families to supplement our display on the Life of American prisoners of war at Hỏa Lò. It would help … give a multidimensional perspective for visitors.”

Wilber said: “My feelings from my first trips are hard to describe. They were intense to the degree of being almost magical. I was so happy and thrilled by so many events and discoveries.

“One of my strongest memories relates to the resilience of the people, coupled with their kindness.”

|

| The spot, the man: Wilber (C) poses with Bùi Bác Văn (L) at the site where his father’s parachute landed in Thanh Tiên Commune, Nghệ An Province. Van was the first to reach the place and also bury the remains of the co-pilot, 50 years ago. |

At Vinh City in 2015, Wilber met Bùi Bác Văn, the first person to run to his father when he landed on the ground with parachute. Văn, 15 years old then, found the remains of the co-pilot and buried them.

“For the first time after 47 years, I had found out what happened to the other pilot. His surviving family was relieved to finally know that someone had taken care to bury the remains of their loved ones.”

Later he also met with the widow of the pilot who downed his father’s plane and had lunch at her home in HCM City.

Wilber has met several times with the former commander of Hỏa Lò prison, senior Colonel Trần Trọng Duyệt, in Hải Phòng, and visited Bùi Bác Văn and his entire family in Vinh City.

“It was an honor to meet with a man who had such a great responsibility regarding the welfare of the detained American prisoners. It was meaningful for me when he told me that he remembered my father’s smiling face because that is how I remember my father too,” Wilber said.

|

| Catching up: Wilber (third left) meeting with Senior Colonel Trần Trọng Duyệt (fourth left)former commander of Hỏa Lò prison, in May 2016. |

Inspired in Việt Nam

“I attribute my success in my many trips to Việt Nam to the many kindnesses and the helpfulness of the people I have met in Việt Nam.

“The more trips I make, the more my network expands. Recently, Madame Binh (former Vice President) received me and we discussed important work going on in Việt Nam today. I have met with Chuck Searcy, an American who has devoted his life to peace and has helped to resolve issues related to Agent Orange and unexploded ordnance.

“There are so many people in Việt Nam who inspire me. I could write pages regarding the many helpful connections I have developed in my many trips to Viet Nam.

“My primary reason, among several reasons, for these continuing trips to Việt Nam is to document the reasoned position against the war that my father developed and communicated while he was interned.

“I believe that the anti-war positions developed and communicated from Hỏa Lò is an important aspect of the history of the American anti-war movement that many people do not realise.” --VNS